Hidden in plain sight: the nobility of Tudor Ireland

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 1(Jan/Feb 2012), Volume 20

Thomas Butler, 10th earl of Ormonde (1532–1614), attributed to the Flemish master Steven van der Meulen, showing the Irish peer as the quintessential early Elizabethan noble-courtier. (National Gallery of Ireland)

It was a book that was ‘certain to have reverberations in the field of Anglo-Irish history’. Thus Hugh Kearney praised Laurence Stone’s epic exploration of the English nobility, The crisis of the aristocracy, 1558–1641 (1965), in a review published by Irish Historical Studies in 1966. With Stone’s opus to serve as a model and stimulus, Kearney opined, it was only a matter of time before the nobility of Ireland—specifically the élite group who comprised the country’s lay peerage—would come under similar scrutiny. To an extent, Kearney was correct. There is a broad and sophisticated body of research on the Irish peerage of the Stuart era by scholars such as Victor Treadwell and Patrick Little. Today the peerage of seventeenth-century Ireland continues to attract research students, while Jane Ohlmeyer’s forthcoming study of the Stuart peerage in Ireland is eagerly awaited by academics at home and abroad.

Tudor historiography

In one important respect, however, Kearney was mistaken, for historians of sixteenth-century Ireland have been much less inclined to study the peerage of that century. Instead, the nobility have been sidelined as historians have tended to focus—broadly speaking—on two over-arching themes: the character of Tudor rule in Ireland and questions of identity relating to the major political-cultural groupings on the island, most commonly rendered as New English, Old English and Gaelic Irish. This varied corpus of work, whose classic statements were written by Ciarán Brady, Steven Ellis and Brendan Bradshaw, and more recently by Hiram Morgan and David Edwards, has made Tudor Ireland a dynamic and confident field of historical enquiry. Long gone are the days when the eminent don of University College London, Sir John Neale, presented the young Nicholas Canny with the condescending challenge of making ‘sixteenth-century Ireland interesting’ to a British academic audience. But what is missing from all this scholarship is an interest in the nobility on a scale comparable to that which exists for Stuart Ireland and for many other European countries and regions in the late medieval and early modern periods.

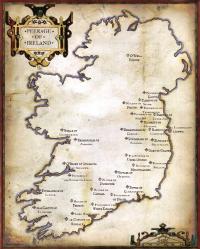

This detail of Abraham Ortelius’s Elizabethan map of Ireland highlights four noblemen in the central third of Ireland—the earl of Clanrickard and the barons of Delvin, Slane and Dungannon. (Cartographica Neerlandica)

This is not to say that the nobility have been completely ignored. Notably, the Fitzgerald earls of Kildare and of Desmond and the Butler earls of Ormond have been explored comprehensively in histories by Steven Ellis, Vincent Carey, Anthony McCormack and David Edwards. But, despite their many qualities, these contributions do not satisfactorily solve the problem of the dearth in peerage studies. One reason for this is that these works are interested in using individual peers and noble dynasties as vehicles to explore other issues, such as the nature of Tudor rule and interventions in Ireland, and shifts in regional politics. The nobility of these men is a secondary consideration rather than a central issue. Moreover, these books concentrate on the magnates, and thus two crucial aspects of noble studies have remained neglected: the lesser nobility and the peerage as a whole. These are serious gaps in our knowledge that need to be filled.Many of the key developments in Tudor Ireland can and should be seen as noble-inspired in one way or another. And really this is because the nobility were absolutely fundamental to the island’s geo-political fabric. Much of Ireland was dominated by the peers, who owned great swathes of land and presided over networks of support that, in some cases, could rival that of the Crown. Nobles were among the most important people in the land, and though government officials came and went, noble houses could—and did—endure for generations. Thus the boy-king Edward VI recorded in his diary when royal letters were sent to the leading peers of Ireland, while cartographers of Elizabethan Ireland like Laurence Nowell and Abraham Ortelius depicted the country not simply in terms of rivers, hills and towns but in terms of noble houses and their regional power-bases. To understand the nobility of Ireland, then, is to understand Ireland itself in the sixteenth century. The preoccupation of historians with the tripartite division between New English, Old English and Gaelic Irish obscures another essential cleavage in politics and society: that which existed between lords and commons.One of the faults that can be levelled against the historiography of sixteenth-century Ireland is that—with honourable exceptions—it has been rather insular. This need not be so. Among the attractions of studying the nobility of Tudor Ireland is that it affords us fresh insights into old problems and has unrivalled scope for comparative approaches, because the problems confronted by the nobility of Ireland—maintaining their status whilst coping with the twin challenges of the aggrandising state and the Reformation—were very much of a kind with those faced by their counterparts in Britain and in continental Europe. From a noble perspective, very little about Ireland is exceptional.

The approximate locations of the Tudor peerage of Ireland. The lesser nobility of Munster and south Leinster have yet to be properly studied. (Tomás Ó Brogáin)

New developments

Happily, there is already evidence of an awakening of interest in the Irish peerage in Tudor times. More studies of individual nobles and noble dynasties are being published—for instance Valerie McGowan-Doyle’s monograph on Lord Howth and his politicised chronicle, The Book of Howth. More to the point, historians are at last advancing substantial pieces of work that treat of peers as members of a wider noble caste. Significantly, three of these scholars participated at a conference—‘Nobility in Early Modern Ireland’—held at NUI Galway in May 2009. Brendan Kane’s 2010 monograph, The politics and culture of honour in Britain and Ireland, 1541–1641, contains a great many fresh insights into the Tudor peerage of Ireland using a range of sources in English, Latin and Irish, and also has the distinct merit of bringing British and Continental theories on nobility to bear on the Irish case. Meanwhile, Christopher Maginn’s contribution, a ground-breaking study of the Gaelic peers during the Tudor period, has been published in the Journal of British Studies. The most recent addition to this body of work, my own A European frontier elite: the nobility of the English Pale in Tudor Ireland, 1496–1566 (2012), is the first book-length treatment of a group of Tudor peers in Ireland, and is also the first book to focus on lesser nobles. I have tried to show that the nobility were a distinctive element within Pale society: their status as peers brought them into regular and formalised contact with the Crown, which ordinary members of the gentry did not enjoy. This unique relationship placed the nobles between a rock and a hard place when the aggressive regime of Thomas, earl of Sussex, forced the peers to choose between loyalty to the government and solidarity with the Pale gentry, who had begun an anti-government protest movement. If we look at the Pale peers from a European perspective, their responses to changes in their political environment often seem timid: certainly their actions are less sensational than those of Philip II’s rebellious nobles of the Netherlands, or the Scottish lords who deposed Queen Mary. The book offers some reflections on why this should be, and argues that the Pale nobles lacked certain preconditions for radical action, including proximity to rival princes and long-standing privileges and institutions, which they felt bound to defend from the intrusion of the state.

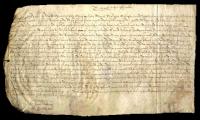

This example of a restored Salved Chancery Pleading concerns the debts of Viscount Gormanston. It describes Jenico Preston, fifth Viscount Gormanston, as ‘a great peere of the Realme . . . with . . . great kinred wealth cowntinaunce and alliance’ in Meath and Kildare. (National Archives of Ireland)

Future developments

Despite this rise in interest, the peerage remains the great unessayed topic of Tudor Ireland; we are still waiting for a comprehensive study of the nobility of the sixteenth century. Did the peerage of Ireland experience its own ‘crisis’, comparable to the one Stone detected in the English peerage from the reign of Elizabeth? It would seem that for many nobles the intensification of English control over Ireland did usher in crisis, but the question needs close examination, especially in the light of recent research, which suggests that several nobles profited by and contributed willingly to the forceful expansion of English rule. Besides this, a myriad of noble themes are in need of research. Certainly there is scope for more studies of individual nobles and dynasties: the Burke earls of Clanrickard are obvious candidates. Another approach would be to study a regional noble grouping. While we now have detailed examinations of the earls of Desmond and Ormond, little or nothing is known about the abundant lesser nobility of Munster and south Leinster—and until we know more about the smaller fry, an accurate picture of the peerage will remain elusive. Tudor noblewomen remain chronically understudied. Again, the way forward has been shown by historians of aristocratic women in Tudor England like Barbara Harris, but this research has yet to resonate much in Ireland. A great many other questions can be posed: how much land did the nobility hold, and how did they manage their estates? How did nobles relate to other nobles, to their spouses, to government officials, to their social inferiors?The perennial problem for historians of Tudor Ireland is source material. There are some topics, such as the activities of the sixteenth-century House of Lords, which, unless fresh evidence is brought to bear, will remain benighted. Nonetheless there is a large corpus of sources that historians’ persistence, archival restoration and technological innovation has made much more accessible to the Irish historian, and which opens new possibilities for the student of nobility. Here the work of David Edwards has been exemplary. His and Brian Donovan’s British sources for Irish history, 1485–1641 (1997) identified a wealth of underused or unused primary sources on Irish aristocrats (and on many other areas) held in repositories in Britain. A great many of these sources were drawn upon for Edwards’s monograph on the Butlers of Ormond, but he also utilised a plethora of Irish-based archival sources, proving conclusively that there is much beyond the default primary source for Tudor Ireland, the State Papers Ireland series. Perhaps the most exciting of these other sources are the Salved Chancery Pleadings. The National Archives of Ireland has recently completed the restoration of thousands of these statements by sixteenth-century plaintiffs and defendants, many of whom were peers or their close relatives. These documents are now in much better condition, and the conservation work has even uncovered new items. Finally, the many digitisation projects currently in operation, such as State Papers Online, are making the task of accessing documents and books held in overseas repositories increasingly easy for Irish-based scholars.The nobility of Tudor Ireland have traditionally been overlooked by Irish historians; in spite of their obvious importance, they have been hidden in plain sight, as debate has tended to focus on other areas. Thankfully, this trend seems to be in reverse. Now, students of nobility have models to emulate, theories to modify or overhaul, and unrivalled access to a range of sources that is richer than commonly supposed. It may well be that soon the historiography of the Tudors’ Irish peerage will be as profound as that of the Stuarts’, bringing Kearney’s 1966 prediction to belated fulfilment. HI

Gerald Power lectures in history at Metropolitan University, Prague.

Further reading:

B. Kane, The politics and culture of honour in Britain and Ireland, 1541–1641 (Cambridge, 2010).C. Maginn, ‘The Gaelic peers, the Tudor sovereigns, and English multiple monarchy’, Journal of British Studies 50 (July 2011), 566–86.G. Power, A European frontier elite: the nobility of the English Pale in Tudor Ireland, 1496–1566 (Hannover, 2012).