Hibernia Romana? Ireland & the Roman empire

Published in Features, Issue 2 (Summer 1996), Pre-history / Archaeology, Pre-Norman History, Volume 4

Emperor Claudius – invaded Britain in AD43.

A number of areas are worth exploring in this regard: not only the possibility of a Roman invasion of Ireland but also Roman geographical knowledge and perceptions of Ireland and Roman attitudes to their empire generally. Whilst debates about an invasion of Ireland, however fascinating, may always be inconclusive, it is ironic—Roman perceptions of space and power being what they were—that Rome did not need to set foot in Ireland in order to claim imperium over it.

Greek geographers

First we must establish Ireland’s place in the Roman world in geographical terms. The first known geographer to mention Ireland is the Greek Pytheas of Massilia, who, according to a later historian Polybius, made a journey in which he at least visited Britain. Whether he landed in Ireland we do not know, but we can be confident that he learned of its existence. It is possible that later authors, principally Strabo and Diodorus Siculus, used the work of Pytheas as a source for their writings. Diodorus Siculus, a first-century author writing in Greek, mentions an island in the north on which there was a magnificent spherical shrine to the god Apollo, adorned with many votive offerings. It has been suggested that this may have been Navan, which had been visited in the second century BC by a Greek or Phoenician traveller. This individual brought a gift of a barbary ape, the remains of which have been found at the site.

It is not until the works of Latin authors mention Ireland that we receive a clearer picture. There is no doubt that the Romans knew of the existence of ‘Hibernia’, long before any direct contact, as the Greeks did of ‘Ierne’, their name for Ireland. Better knowledge was prompted by better communication, mainly as a result of trade. The later, and probably most famous of early geographers, Claudius Ptolemy, also notes that the ports and coasts of Ireland were well-known by traders.

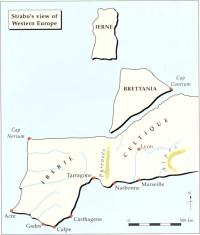

Fig 1. Strabo’s view of Western Europe –

claimed that Ireland was ‘barely habitable on account of the cold’

Caesar

The first Roman writer to refer to Ireland is Julius Caesar, in his account of his campaigns in Gaul, which was probably published around 50 BC. Caesar considered Ireland to be two-thirds the size of Britain, from which it was separated by a strait of equal width to that between Britain and Gaul. Pliny the Elder merely tells us that it was the same breadth as Britain, but two hundred miles shorter, adding that the shortest route by sea to Ireland was thirty miles. In the period between these two authors, Strabo wrote a vast work of geography on more ethnographical lines concerning the ‘inhabited world’. He placed Ireland north of Britain, on the limits of the known world, and claimed that it was ‘barely habitable on account of the cold’. (See fig.1) He generously considered the inhabitants more savage than the Britons, since they are man-eaters as well as heavy-eaters, and since they count it an honourable thing when their fathers die to devour them, and openly to have intercourse not only with other women, but with their mothers and sisters as well; but I say this only with the understanding that I have no trustworthy witnesses for it.

Another author, Pomponius Mela, echoed the theme that the Irish were more savage than any other race. He also notes that Ireland was unsuitable for growing wheat, but was so rich in grass that cattle would burst from eating too much if unrestrained. The lack of arable farming seems to be borne out by pollen records which suggest a decrease in agricultural activity between 100 BC and AD 200. Solinus, who wrote in the third century AD and who may have depended on the work of Pliny and Mela, claimed that the Irish were an inhospitable race, but incidentally is the first to refer to the lack of snakes before the arrival of Patrick. The fifth century writer Orosius describes Ireland as being inhabited by the Scoti, and indeed surpassing Britain in climate and fertility.

Tacitus

Despite this miscellany of references, by far the best evidence for Ireland remains the work of Tacitus, and it is certainly the most important for our purposes.

Ireland…is small in comparison with Britain, but larger than the islands of the Mediterranean. In soil and climate, and in the character and civilisation of its inhabitants, it is much like Britain; and its approaches and harbours have now become better known from merchants who trade there.

With the advent of the Romans, geographical knowledge continued to be important, though for different reasons. Provinces and other regions were explored from a military point of view. Indeed, we could claim that Roman geographical knowledge advanced hand-in-hand with the development of military professionalism. Intelligence became important and was chiefly gained from merchants and traders. It is interesting to note that Tacitus specifically mentions these individuals in his description of Ireland. One good example of the gathering of intelligence is recorded by Julius Caesar, who sent a soldier named Volusenus to collect information on British inhabitants, harbours, and landing places and to produce a report. We know also that Caesar commissioned the first known world map. His adoptive son, who became Augustus, the first emperor of Rome, developed this attention to maps further, highly interested as he was in surveying for fiscal purposes. With him also grew the symbolism of empire manifest in Augustan literature, of which more later.

Claudius

From these rather colourful, but incomplete, geographical accounts of Ireland and its inhabitants by Greeks and Romans, we now must turn to the evidence for an invasion. Any such attack would have come in the aftermath of the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43. Bede, relying largely on the accounts of the Latin historians, Orosius and Eutropius, states in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, that the emperor Claudius attacked Britain ‘wishing to prove that he was a benefactor to the state, (and) sought to make war everywhere and to gain victories on every hand’. This is a surprisingly accurate appraisal of Claudius’s motives. He was certainly no soldier, having come to power rather ingloriously as the candidate of the Praetorian Guard (the bodyguard of the emperor), the murderers of the previous emperor, Caligula. Claudius had to assert his position with a clear-cut victory and travelled to Britain himself for the final campaign in AD 46. He returned to Rome after six months to hold a magnificent triumph, the traditional medium for the celebration of victories by those Roman generals who had participated personally in a victory. Claudius had thereby satisfied the army whose support he desperately needed.

Agricola

Agricola

We must return to Tacitus as our starting point in deciding whether or not there was a subsequent Roman invasion of Ireland. He states that

Agricola started his fifth campaign (AD 83) by crossing the river Annan; and in a series of successful actions subdued nations hitherto unknown. The side of Britain that faced Ireland was lined with his forces. His motive was hope rather than fear. Ireland, lying between Britain and Spain, and easily accessible also from the Gallic sea, might serve as a very valuable link between the provinces forming the strongest part of the empire.

This is significant both because it shows an awareness of strategy, and because Tacitus goes on to note that, on several occasions, Agricola claimed that he would need only one legion to conquer Ireland. Tacitus also records that Agricola befriended an Irish prince, possibly with the intention of using him as a bargaining tool or collaborator in a conquest. This has been taken by some scholars to indicate that there was an invasion, and they also quote Juvenal, who wrote that ‘we have advanced our armies to Ireland, and the recently conquered Orkneys, and Northern Britain with its short clear nights’. But Juvenal was a satirist, and as such, using his work as evidence is problematical; he may be referring to invasions, but equally, he may refer to failures! It should also be pointed out that the Orkneys and Northern Britain were never fully invaded or organised, and advancing armies to a region is quite different from invading it. Finally, the later Chronicle of Tysilio, which is corroborated by the Norman propagandist Geoffrey of Monmouth, mentions a Romano-British expedition to conquer Ireland during the reign of Claudius, but the details of this are unclear.

Fig.2. Roman coins such as these of Augustus and Trajan depict emperors holding the earth in such ways as to suggest power over it.

Drumanagh

Until very recently there has been little archaeological evidence for a Roman invasion. The astonishing find of a ‘Roman fort’ at Drumanagh fifteen miles north of Dublin would seem at first sight to show that there was an invasion. This need not be the case, and at any rate we cannot be sure that the final results will be conclusive. The site has not been excavated, so any conclusions drawn now could be dangerously premature. A proper scepticism should also be maintained because the site is unique and no other ‘forts’ are known or evidenced. It is also entirely probable that, because of trading links with Britain, many Roman and British merchants travelled to Ireland with their goods, and the idea that this ‘fort’ was a  trading outpost should not be discounted. Gold coins have already been found near Dublin and at Bray; silver and bronze coins at Newgrange; brooches at Knockawlin and Cashel; occasional finds of grave goods have included Roman or Romano-British items. Richard Warner of the Ulster Museum has noted what he claims to be ‘a Roman grave’ at Kilkenny with a cremation in an urn. He is surely wrong to claim that this evidence implies ‘a strong and secure Roman community’ when he himself admits that the number of Roman artefacts found in Ireland is small and that literary evidence is absent. We do not have to accept that there was an invasion simply because there was some Roman influence in the area. Romans often traded with regions that they did not invade. Only after a full excavation of the site can we examine with any confidence the question of a Roman military presence in Ireland.

trading outpost should not be discounted. Gold coins have already been found near Dublin and at Bray; silver and bronze coins at Newgrange; brooches at Knockawlin and Cashel; occasional finds of grave goods have included Roman or Romano-British items. Richard Warner of the Ulster Museum has noted what he claims to be ‘a Roman grave’ at Kilkenny with a cremation in an urn. He is surely wrong to claim that this evidence implies ‘a strong and secure Roman community’ when he himself admits that the number of Roman artefacts found in Ireland is small and that literary evidence is absent. We do not have to accept that there was an invasion simply because there was some Roman influence in the area. Romans often traded with regions that they did not invade. Only after a full excavation of the site can we examine with any confidence the question of a Roman military presence in Ireland.

This is not much to go on but the possibility of an invasion remains. Claudius’s intentions when he invaded Britain were almost certainly to conquer the whole archipelago, and he was not affected by any notion of frontiers or controlling only part of the islands. He knew of Ireland, and that it was close to Britain. It is possible that Agricola, in AD 83, tried to invade Ireland but was unsuccessful, or that he had one legion on standby for such an expedition, supported by Irish allies, but permission was not forthcoming from Rome. Some suggest that he was called home in disgrace which prompted his son-in-law Tacitus to write his biography. Perhaps the tone of Tacitus’ account implies an old man who still rankled in his retirement about his recall before he could launch his final conquest.

The evidence against an invasion is quite strong: no ancient source known specifically mentions one. But if there was no invasion or if there was an unsuccessful foray which was not followed up, why was this the case? Around this time there is a loss of impetus generally in the Roman conquest of Britain, possibly caused by military problems elsewhere in the empire, in the Rhine and Danube regions. The Roman army was not large enough to fight on many fronts, and thus soldiers may have been withdrawn from Britain to conflicts elsewhere. The drive to expand in Britain never really returned, which may explain why there was no subsequent invasion of Ireland. After the mid-second century, Roman frontiers were always under pressure from some direction. By this stage they certainly knew what Ireland was like and that it probably was not worth the trouble of invasion. Additionally, Solinus notes that the Irish were an unfriendly, warlike people who smear the blood of slain enemies on their faces and so do not distinguish from right and wrong. Ergo, Ireland had not been ‘romanised’, let alone conquered by AD 200.

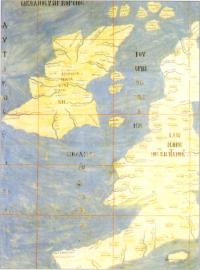

Fig.3. The Hereford Map(c. AD 1300),in which Augustus is shown issuing orders to three surveyors(mensores). Ireland,above the heads of the mensores, is depicted as being part of the Roman world.

Frontiers

Instead of speculating on the Roman invasion theory let us consider Roman attitudes towards their empire and the wider world and their conceptions of space and power. Frontiers as we understand them did not exist before the seventeenth century, and certainly not in Roman times. Two main reasons for this have been identified. First, poor geographical knowledge meant that the Romans tended to underestimate the distance between the centre of their empire and its periphery; second, regions beyond the centre were perceived in terms of power rather than territory. Having power over, influence over, or even connections with a region was enough for the Romans to claim it as part of their empire, regardless of whether they had good geographical knowledge of it. Thus the emperor Augustus could claim that he had forced the mighty Middle-Eastern empire of Parthia ‘to seek as suppliants for the friendship of the Roman people’, even though there was no direct conflict. Contemporary poets expressed the belief that he could bring the whole world under Roman rule; indeed, the poet Virgil, in his epic poem the Aeneid, promises that the Romans will enjoy ‘power without end’ and that the Roman empire will rule over the whole world. These sentiments were not without parallel. The historian Dio paints a colourful picture of the triumph celebrated by Julius Caesar in 46 BC in celebration of his victories in Gaul, Egypt, Pontus, and Africa:

this occasion he climbed the steps of the Capitolium on his knees, neither casting his eyes upon the chariot dedicated to Jupiter in his honour, nor upon the image of the oikoumene [literally ‘the inhabited world’] lying beneath his feet, nor upon the inscription which it bore; but later he had the word ‘demi-god’ erased from the inscription.

Despite this magnanimous gesture, the implication is that Rome enjoyed power over the whole world.

Other poets and writers follow suit: Livy, the great historian, stated that Rome was at the ‘head of the world’, and Horace boasted that ‘the fame and majesty of the empire had been extended to the rising of the sun from its western couch’. Additionally, Roman coins depict emperors holding the earth in such ways as to suggest power over it. (See fig. 2) Of course, whatever the boasts of the literary fraternity, or any other symbol, this was not really the case. Augustus was a great conqueror, but was painfully aware of how the empire could be over-extended, especially after a disaster in Germany in AD 9, when three whole legions fell to German tribes. His advice to his successor Tiberius, reported in a famous passage of Tacitus, was ‘not to extend the empire beyond its limits’. The Latin is ambiguous, and what this phrase actually means has been the subject of dispute. It may mean beyond the empire’s present limits, but it could equally mean beyond its potential limits, perhaps the coastlines of the empire.

Beyond the frontiers

At any rate, we have established that the Romans, or at least their poets, aspired to conquering and controlling ‘the inhabited world’. But to what lengths were they prepared to go? Were the words of the poets simply imperialist rhetoric? Augustus, we saw, was careful; his diplomatic rather than military victory over Parthia is testament to that. Tiberius consolidated rather than expanded. His successor Gaius Caligula was at best incompetent, at worst insane. Claudius needed the military victory, but chose the victim carefully. After Claudius, there was some expansion in Britain, but this eventually came to a standstill. We have to turn to Strabo to understand our problem. He stated that the people beyond the empire were treated as part of it. Clemency and friendship were extended to them, but in most cases these realms were considered unsuitable for occupation owing to weak internal infrastructures. Only those parts of the oikoumene which were considered worthy were to be occupied and organised, although the rest could certainly be exploited. This is also stated by the earlier historian Polybius, who notes that only the known parts of the inhabited world were ruled by Rome.

The arguments and views are complex, and in a sense contradictory; most Romans surely knew that they did not control the whole world, otherwise how could any imperial expansion take place? However, we must now try and fit Ireland into this picture. It is clear that Roman geographical knowledge of Ireland was not good, with its climate considered by Strabo to be uninhabitable, at least for Romans in their togas! It probably lacked the infrastructure, either economic or administrative, that would have appealed to the Romans. Too much initial organisation would have been necessary in order to exploit the new province to the limit. Why would the Romans invade Ireland if there was little to interest them? Rome only took over economically viable territories; she did not conquer indiscriminately. The Panegyric on Constantine Augustus, the first Christian emperor of Rome, states that Ireland was not thought worthy of conquest; the effort was probably not worth the gain.

Conclusion

Taking into consideration that the claims and hopes of Roman poets did not always reflect the true picture, and that Ireland had little to offer in terms of wealth to the Romans, is there really a case for a Roman invasion of Ireland? The fact that it is featured on maps of the Roman empire is not important. (See fig. 3) These were not representations of regions directly controlled by the Romans, but rather maps of all areas over which the Romans claimed to have influence. This is an important distinction as communication or trade with Ireland was not a precursor to or a result of invasion. Conquest was not a necessary prerequisite of ‘rule’ in a Roman sense.

Colin Adams is a postgraduate student in ancient history at the University of Oxford.

Further reading:

P.M. Freeman, ‘Greek and Roman views of Ireland: a checklist’, in Emania 13 (1995).

C. Nicolet, Space, Geography, and Politics in the Early Roman Empire (Michigan 1991).

C.R. Whittaker, Frontiers of the Roman Empire, a social and economic study (Baltimore 1994)

P. Salway, The Oxford Illustrated History of Roman Britain (Oxford 1993).