Hervey Morres and ‘the Montmorency imposture’

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2020), Volume 28‘I do not hesitate to say that a more impudent claim was never successfully foisted on the authorities and the public.’

By Conleth Manning

In 1815 certain members of the Morres family, who were descended from Hervey Morres of Castlemorres, Co. Kilkenny (1625–1724), were by royal licence allowed to ‘re-assume their ancient and original surname of Montmorency’. Those so named were:

- Sir Francis-Hervey, Viscount Mountmorres and Baronet. (The title passed to him from his half-brother, Hervey Morres, the 2nd viscount, who died in 1797 and who bequeathed the Castlemorres estate, which was not entailed, to his sisters Sarah Pratt and Letitia, Lady Antrim. Sarah’s son Harvey inherited the Castlemorres estate in 1831 and adopted the surname de Montmorency. His descendants continued to live at Castlemorres until 1924.)

- Lodge-Evans, Lord Baron Frankfort of Galmoye. (A first cousin of Viscount Mountmorres, he was prominent in Irish political life, serving as an MP in the Irish parliament from 1768 to 1800 and holding posts such as under-secretary (1795) and lord of the treasury (1797). He was made Baron Frankfort of Galmoye in 1800 and Viscount Frankfort de Montmorency in 1816.)

- Sir William-Ryves Morres of Upperwood, Baronet (a first cousin of both of the above).

- Reymond-Hervey Morres, Lt.-Col., 9th Regiment of Dragoons (a nephew of Viscount Frankfort).

- Hervey-Francis Morres, Capt., 21st Regiment of Foot (a son of Viscount Frankfort).

The process was fully endorsed by the deputy Ulster king of arms, William Betham. The descendants of these men and of Harvey, son of Sarah Pratt (née Morres), have continued to use the surname de Montmorency ever since.

‘A cock-and-bull pedigree’?

Above: Fig. 1—A small watercolour of Hervey Morres that can be found pasted to the rear of the title-page of a copy of his 1821 book on Irish round towers, which belonged to Sir William Betham and is now in the Joly collection in the National Library of Ireland. (NLI)

This change of name apparently went unquestioned in Ireland and Britain until the 1890s, when it was strongly criticised by John Horace Round, a historian of the Normans in Britain, in an article titled ‘The Montmorency imposture’. He claimed that the Morres family were not descended from the Montmorencys:

‘We may hope and believe that in the present day no officer of arms would behave like Sir W. Betham, and certify, as “established on evidence of the most unquestionable authority” a descent which is not merely “not proven”, but can be absolutely disproved.’

He further described it as ‘a cock-and-bull pedigree, or genealogical nightmare, which, for sheer topsy-turveydom, has, I venture to assert, never been surpassed … I do not hesitate to say that a more impudent claim was never successfully foisted on the authorities and the public.’

The surname Morres is the same in Ireland as Morris and sometimes Morrisey, all being variations of the Anglo-Norman de Mareis or de Marisco, which has sometimes become Marsh or Moore in England. E. Naomi Chapman, the author of a 1928 book on the Morris family in Ireland, agreed with Round and was supported by Goddard Orpen in her opinion. In addition, Eric St John Brooks, an authoritative scholar of the Anglo-Normans in Ireland, published an extended article on the family of Marisco in Ireland (in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland for 1931–2) that showed no connection between the Morres/Morris/de Marisco family and the de Montmorencys. Major Hervey Guy Francis Edward de Montmorency DSO, a descendant of the above-mentioned Kilkenny family, disputed Round and Chapman’s conclusions and, while apparently unaware of Brooks’s paper, subsequently published his own defence of the claim.

The extraordinary career of Hervey Morres (1767–1839)

Above: Fig. 2—The supposed effigy of Hervey de Montmorency at Dunbrody Abbey from a copy of Morres’s 1828 book. Giraldus Cambrensis recorded that de Montmorency entered the monastery of Canterbury around the early 1180s, so Morres chose to depict him with ‘his shirt of mail appearing, characteristically, beneath his religious garment’. (Jane de Montmorency Wright)

While Betham was blamed by Round for the ‘imposture’, it is clear, especially from his 120 letters to Betham dated between 1810 and 1839 and now in the National Library of Ireland, that a man called Hervey Morres, or Col. Hervey de Montmorency Morres, was the principal instigator of the whole affair. He got to know Betham soon after the latter’s arrival in Ireland and relentlessly pursued his claim with Betham that the name Morres was originally de Montmorency and that Hervey’s own Tipperary family was the premier branch of this family in Ireland. He had two books privately published in Paris, in 1817 and 1828, to support his claim and clearly, before 1815, had persuaded both William Betham and the influential Protestant branch of the Morres family in County Kilkenny of the veracity of his claim. He was annoyed that his name was not included in the list attached to the royal licence of 1815, an omission that was probably due to the fact that he had joined the French army in 1811.

This Hervey Morres (Fig. 1) had quite an extraordinary career. Born near Nenagh, Co. Tipperary, to an impoverished Catholic gentry family in 1767, he joined the Austrian army in 1782 at the early age of fifteen. In 1794 he married a wealthy German baroness and returned to Ireland to live at Knockalton near Nenagh. He joined the United Irishmen and was involved in the 1798 rebellion in a leadership role. He was subsequently arrested in Hamburg and brought back to Ireland for trial with James Napper Tandy. Tandy was found guilty of high treason and condemned to death but was granted a royal pardon. Morres was eventually released without trial in December 1801. His young German wife had died while he was in jail, and after his release he married the wealthy widow of his cousin, Dr John Esmonde, who had been executed for his part in the 1798 rebellion. They set up home initially in Malahide, then in nearby Streamstown and finally in Russell Street, Dublin. During this period he occupied himself with research on his family, on Irish history and topography and was also involved in the Catholic cause, in relation to which he published a pamphlet on ‘the veto’ in 1810. His historical and topographical researches eventually bore fruit in the publication of his book on Irish round towers in 1821, the first published on the subject. He also paid Betham to do further research on the Morres family and to draw up a family pedigree.

Hervey Morres’s name appears in a list of suspects drawn up around the time of the Emmet rebellion in 1803:

‘Description: 5 feet 10, genteel well looking, stout made, sharp nose, wears powder, mostly in blue and military looking, about 40 years, near sighted, dark complexion. Residence: Malahide, on the first turn to the right—on right hand, white house, 2 stories, window sashes black, black rails in front, a field opposite. Observations: Was arrested with Napper Tandy in Hambro, was in Austrian service, is a man of considerable abilities, deeply implicated in 1798.’

(NAI Rebellion Papers 620/12/217, p. 48)

The house in Malahide survives and is at present the premises of Manor Books.

In 1811, while the United Kingdom was at war with France, Morres managed to make his way there and, after some difficulties and an interview with Napoleon himself, obtained a commission as a colonel in the French army. His wife and family joined him in Paris soon afterwards. He became a French citizen in 1816 and continued to live in Paris, and latterly in St Germain-en-Laye near Paris, until his death in 1839. Part of his motivation in claiming to be a de Montmorency was that the de Montmorencys were the premier barons of France and Morres craved acceptance as the head of the Irish branch of the family. To his great disappointment, the French de Montmorencys never accepted his claim.

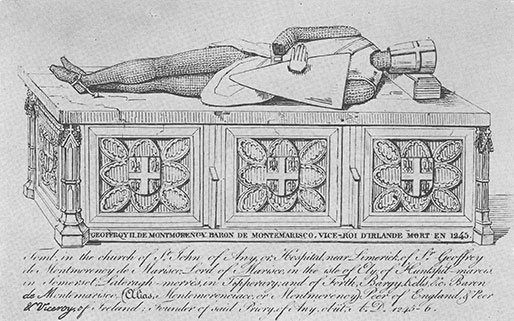

Above: Fig. 3—A print of the effigy of a knight at Hospital, Co. Limerick, from Morres’s 1828 book. He added the fictitious tomb surrounds with the de Montmorency arms, and further embellished the print by adding an inscription to the base of the tomb surround. (NLI)

The only person connected with Ireland in the medieval period who appears to have borne the name de Montmorency was Hervey de Montmorency, an uncle of Strongbow, who was one of the leaders of the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the late twelfth century. He was granted territory in south-west County Wexford and founded the Cistercian abbey of Dunbrody. He died without legitimate issue, but Morres claimed that Geoffrey de Marisco, who was twice justiciar of Ireland (1215–21 and 1226–8), was a brother of Hervey de Montmorency and the ancestor of the Morres family in Ireland. This supposed fraternal connection is quite simply untrue. Morres also claimed Geoffrey Fitz Robert, the founder of Kells Priory, Co. Kilkenny, as a member of the family, and without any evidence added ‘de Monte Marisco’ after his name. This latter fiction is still being repeated to this day in otherwise scholarly sources, as for example the Monastic Ireland website (monastic.ie).

Fabricated illustrations

Some of the illustrations that were specially commissioned by Morres for his two books show clearly that he was not beyond deliberately fabricating evidence to suit his purpose. A number of the illustrations of burial monuments, such as those of Hervey de Montmorency at Dunbrody (Fig. 2) and of Jordan de Marisco and his wife and Sir Oliver Morres, both supposedly at Holy Cross Abbey, are complete fabrications. In another print he added unlikely tomb surrounds with the de Montmorency arms to a surviving anonymous effigy at Hospital, Co. Limerick (Fig. 3), and claimed it as the tomb of Geoffrey de Marisco. This image was reproduced in a recent book on the military orders in Ireland, some of the authors having mistaken these fictitious surrounds as genuine.

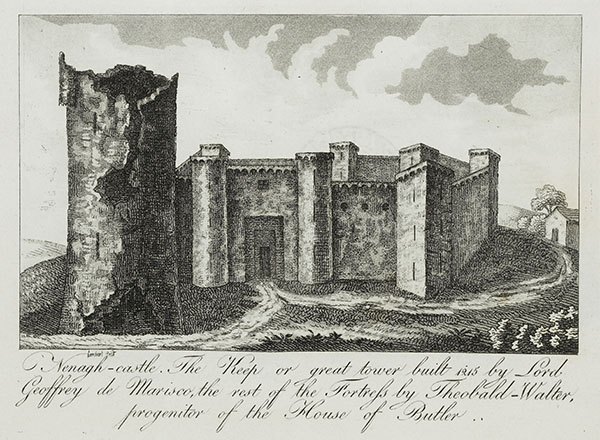

Most of the illustrations of castles and religious houses in Morres’s two books, while poorly depicted, are not entirely inaccurate. An exception is Nenagh Castle, where Morres has added a fictitious and completely unlikely massive towered enclosure to the surviving circular keep (Fig. 4). There is also a print of his family home at Rathnaleen, near Nenagh, and it is difficult to know how much credence can be given to it. It does not survive and even its exact location is uncertain. It is depicted as a five-bay two-storey house with attached wings to the rear. A ruined castle is shown beyond it, which was relatively small in the version of the print published in the 1817 book. He must have considered it insufficiently impressive and had the engraver enlarge it for the 1828 book.

Above: Fig. 4—A print of Nenagh Castle from the 1828 book. The strange towered enclosure to the right of the circular keep is a complete fabrication. (NLI)

It was, of course, important for Irishmen seeking commissions in mainland European armies in the eighteenth century to produce pedigrees and proof of their family’s standing in Ireland. The Genealogical Office manuscripts contain evidence of many such cases. In 1794, when Morres was to marry the Baroness von Helmstadt, he had to produce evidence of his family’s pedigree, standing and landownership, which was signed by prominent persons in Ireland. Ironically, one of the signatories to this document, as printed in the 1817 book, was John Toler, ‘the King’s Solicitor General for Ireland, member of parliament for the borough of Gorey’, later better known as Lord Norbury, the infamous ‘hanging judge’. From this document we can see that Morres was already claiming to be a de Montmorency and this appears to have been a tradition in his family.

Morres’s cavalier approach to the genealogy of his family has much in common with his contemporary Sheffield Grace, who wrote a number of books on the Grace family that contain many errors of fact, imaginary illustrations of castles etc. and even forged bardic poems. While Morres was an able researcher and his two books contain many genuine historical data, some even used by Brooks in his article on the Marisco family, the information in them and the illustrations need to be treated with circumspection. As the historian District Justice Dermot Gleeson put it, Morres’s books ‘contain some serious inaccuracies and neither the plates nor the place-name identifications are to be trusted; and, in general, all unvouched statements require critical examination’. One has, however, to admire Morres’s powers of persuasion in getting members of an influential ascendancy family to enthusiastically agree to change their surname and in getting the authorities to officially authorise the name change.

Conleth Manning is an archaeologist, formerly of the National Monuments Service.

FURTHER READING

H. de Montmorency Morres, Genealogical memoir of the family of Montmorency, styled de Marisco or Morres (Paris, 1817).

H.G.F.E. de Montmorency, A memorandum explaining the claim of the Morres family to bear the name of de Montmorency (Saffron Walden, 1938).

C. Manning, ‘Delusions of grandeur: the pictorial forgeries of Sheffield Grace’, in J. Kirwan (ed.), Kilkenny studies in honour of Margaret M. Phelan (Kilkenny, 1997).

C. Manning, ‘Colonel Hervey de Montmorency-Morres (1767–1839), soldier, United Irishman, antiquary and controversial genealogist’, in I.W. Doyle & B. Browne (eds), Medieval Wexford: essays in memory of Billy Colfer (Dublin, 2016).