‘Has he called you frigid lately?’

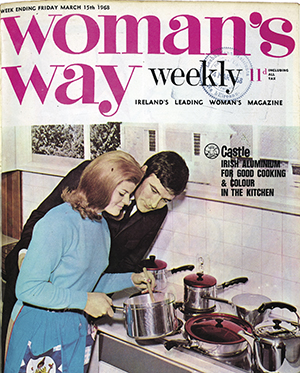

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2018), Volume 26How women’s magazines handled sex and the Irish ‘guilt complex’ in the 1960s.

By Ciara Meehan

Dr Martin Kennedy posed this question in his column for Woman’s Choice magazine in 1968. It was followed by another question, relating to intimacy during pregnancy: ‘How are you to keep him happy during these difficult months?’ The article had every appearance of being yet another piece of advice that encouraged wives to prioritise their husband’s sexual needs but, as one reader who later wrote to the magazine put it, the article actually appreciated that a truly fulfilling sexual relationship required—would you believe it?—more than just male satisfaction!

Dr Martin Kennedy posed this question in his column for Woman’s Choice magazine in 1968. It was followed by another question, relating to intimacy during pregnancy: ‘How are you to keep him happy during these difficult months?’ The article had every appearance of being yet another piece of advice that encouraged wives to prioritise their husband’s sexual needs but, as one reader who later wrote to the magazine put it, the article actually appreciated that a truly fulfilling sexual relationship required—would you believe it?—more than just male satisfaction!

Irish women’s magazines in the 1960s dedicated many column inches to ‘sex education’, which varied from outlining the basics of the reproductive system through to encouraging female enjoyment of intercourse. When read in conjunction with the myriad of letters written to advice columnists Angela Macnamara and Sheila Collins of Woman’s Way and Woman’s Choice, it is immediately apparent why the magazines returned to such topics.

Serious gaps in knowledge

The letters reveal that teenage girls and young women were concerned about pregnancy resulting from a whole range of activities that did not result in intercourse, including close dancing, passionate or French kissing and masturbation. On three separate occasions, teenagers confided in Macnamara about pregnancy fears arising from intercourse that had happened several years earlier. Clearly the lack of proper sex education led to some serious gaps in knowledge.

The letters, however, also reveal another problem in relation to sex knowledge and one that has received less attention—the ‘guilt complex’ experienced by Irishwomen, stemming from the Catholic Church’s and the State’s view of the female body. In the years after independence, both institutions had sought to impose on women standards of idealised conduct. The implications can be seen in the pages of magazines in the 1960s. Female readers treated these publications as alternative confessionals, admitting their fears and concerns about sex. The editors and their staff attempted to reassure them that intercourse was not unnatural but rather was something to be shared and enjoyed.

The bishop and the nightie

In February 1966 Woman’s Way approached the issue of the ‘first night’. The article addressed sex as an act of intimacy rather than just for the purposes of procreation. The word ‘sex’ appears in the subtitle, and ‘climax’ (in relation to the woman) can be found in the main body of the article. Such words are hardly shocking to the present-day reader of women’s magazines whose covers regularly promise ‘ten ways to achieve the ultimate orgasm’. But remember that February 1966 was also the month and year when The Late Late Show, presented by Gay Byrne, found itself in trouble with the bishop of Clonfert. When asked by Gaybo the colour of the nightdress she had worn on the first night of her honeymoon, audience member Eileen Fox replied that she hadn’t worn one at all. She then changed her answer to ‘white’, but the bishop opted to overlook this.

The implication of her quip was clear. In his Sunday sermon, the bishop referred to ‘morally—or rather immorally—suggestive parts of the show’, which he deemed ‘most objectionable’ and ‘unworthy of Irish television’. RTÉ was initially reported as having nothing to say on the matter, but the Irish Times later carried an apology from Gay Byrne for any offence caused. Clearly, then, women’s magazines were pushing the boundaries in a way that television was not able to do. And while the page-length article in Woman’s Way was not explicit and did not provide any instructions about engaging in the physical act, it did offer reassurance to couples anxious about their first intimate encounter.

Sex-positive message

Even more significant is the fact that the article encouraged active participation on the part of the woman for her own benefit.

‘It should be remembered that the bride requires more time to reach a climax than her husband and in the early days it is often extremely difficult for the man, much as he would wish to do so, to wait … It is not uncommon and provided that the wife is understanding and does not exaggerate the difficulty, it will soon resolve itself. She should be aware, too, that her husband may need some guidance and assistance and that her active participation in love-making is a fully-accepted and natural element in a happy marriage relationship.’

This sex-positive message, offered without reference to procreation, was a problematic and unfamiliar one. The language of this article had more in common with Marie Stopes’s Married love or love in marriage than with the traditional marriage manuals published in Ireland. Stopes published her book—intended to be a marriage manual—in New York in spring 1918, just four years after the end of her own first marriage, which she claimed was never consummated owing to her husband’s impotence. Married love looked specifically at the sexual relationship between husband and wife, and she explained:

‘In my own marriage I paid such a terrible price for sex-ignorance that I feel that knowledge gained at such a price should be placed at the service of humanity’.

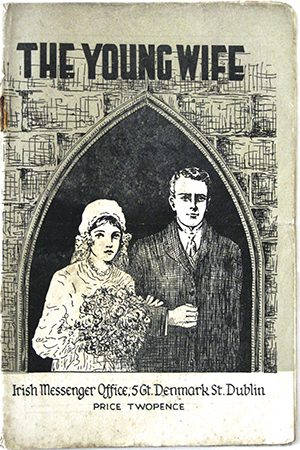

The young wife, a near-contemporary manual published by the Irish Messenger Society that was in its third print run since 1938, did not address the subject of intercourse (it’s no wonder that the bride on the cover looked so apprehensive!) other than to explain that the purpose was to procreate. Foreplay and orgasm—issues explored in Married love—were wholly ignored.

Prudish attitude towards nudity

Above: The young wife, a near-contemporary manual published by the Irish Messenger Society that was in its third print run since 1938, did not address the subject of intercourse.

In the same decade that The country girls was published, the letters pages in women’s magazines carried the stories of women encouraged to believe that modesty meant hiding their bodies from view. This resulted in psychological problems for some brides, as their responsibility shifted from protecting their purity to obliging their husband’s physical desires. Their own pleasure rarely featured in their letters asking for help.

Dan Paddy Andy O’Sullivan, the famed Kerry matchmaker, is reputed to have made over 400 matches during a 25-year period across the 1930s to 1950s. It is alleged that only one failed. While these figures might be open to scrutiny, the explanation offered for the failed match is certainly plausible. As John B. Keane explains in his biography of O’Sullivan, although the pairing had resulted in marriage it had not lasted because the woman was unable to overcome her Catholic guilt, believing that even marital sex was shameful. Plenty of evidence of such thinking exists within the pages of the magazines. ‘Patients’ Postbox’ in Woman’s Way featured a letter from a woman who had been married for ten months and was experiencing difficulty having intercourse because she was ‘very frightened and afraid of pain’. She was not alone.

A woman who had been married nearly a year wrote to the same column, as she was yet to have proper intercourse because she was nervous. One woman confided to Angela Macnamara that after two years of marriage she had not ‘adapted to the intimate side of marriage’, while the following month another woman disclosed that she was fearful of sex and, consequently, she and her husband had not been intimate since the birth of their first child. Similarly, a woman who had been married for ‘some time’ wrote to Sheila Collins in Woman’s Choice about her struggle with the moral implications of being intimate with her husband. Collins attempted to reassure her that married love could be enriched through mutual sexual satisfaction.

The ‘guilt complex’ suffered by such women was the subject tackled by Dr Martin Kennedy in his Woman’s Choice guest contribution, quoted at the start of this article. Whilst the sample of published letters admitting to difficulties is not extensive, that the magazine chose to highlight the issue indicates the universality of the problem. Kennedy blamed Catholic teaching and the social structure in Ireland for conditioning women to think that it was improper to openly enjoy sex. Publications such as The young wife claimed that ‘the physical pleasure’ and ‘the sensual appetite’ are ‘bestowed and willed by God’ and ‘contain not a shadow of sin’. But such urges had to occur within the context of procreation. A woman’s purpose in life was to be a mother, and the object of marriage was to provide a formal framework within which new life could be created. Conception was not a duty according to The young wife, and yet that pamphlet also bizarrely claimed that women who were already pregnant or who had experienced the menopause were permitted to have sex with their husbands as long as the ‘principal aim [of conception] governs and determines each conjugal union’.

Woman’s Way and Woman’s Choice played an important, if overlooked, role in educating their readers. Oliver J. Flanagan, the conservative Fine Gael TD for Laois–Offaly, famously suggested that there was no sex in Ireland before RTÉ—a valid remark if a programme like The Late Late Show is taken into consideration. Nevertheless, while RTÉ did much to open up discussion and bring certain issues into living rooms around Ireland, there were limits to the topics that could be covered, as the ‘bishop and the nightie’ incident showed. The papers of Archbishop McQuaid contain letters from concerned mothers not keen on the magazines their daughters were reading, but McQuaid never intervened (a sign, perhaps, of his diminishing power). Woman’s Way and Woman’s Choice carried on publishing articles intended to help women overcome traditional views of the body, and providing the space for their readers to ask the questions that weren’t being answered elsewhere.

Ciara Meehan is Head of History at the University of Hertfordshire.

FURTHER READING

C. Clear, Women’s voices in Ireland: women’s magazines in the 1950s and 1960s (London, 2017).

M.E. Daly, Sixties Ireland: reshaping the economy, state and society 1957–1973 (Cambridge, 2016).

D. Ferriter, Occasions of sin: sex and society in modern Ireland (London, 2009).

P. Ryan, Asking Angela Macnamara: an intimate history of Irish lives (Dublin, 2011).