Half-Irish and all slave

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2017), Volume 25The life of John Roy Lynch, whose political career during Reconstruction is one of the most remarkable achievements in the pantheon of Irish-American politics.

By Joe Regan

On 3 November 1939, the New York Times reflected on the political career of the recently deceased John Roy Lynch, remarking that he was ‘one of the most fluent and forceful speakers in the politics of the seventies and eighties’. Nonetheless, since John Roy Lynch’s death his name has lapsed into obscurity among historians of the Irish diaspora. The son of an Irish immigrant, Lynch was born a slave. His political achievements provide an inspiring story of possibility and determination in the face of violence and racial hatred. Indeed, the life and works of John Roy Lynch illuminate the complexities of the various Irish experiences in the United States.

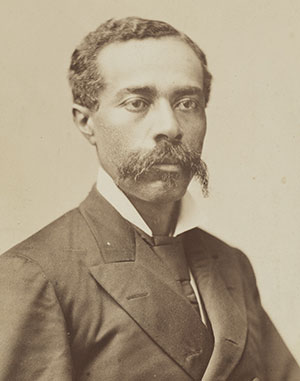

Above: John Roy Lynch in 1883. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

John Roy, the third son of Patrick Lynch and Catherine White, was born on 10 September 1847 on Tacony plantation, Concordia Parish, Louisiana. Patrick Lynch, originally from Dublin, emigrated as a child with his family to Ohio. During the early 1840s, Patrick travelled with his brother to Louisiana. Edward Lynch settled in New Orleans, while Patrick found employment as an overseer in Concordia Parish. The Irish who came to the antebellum South found a society in which the economic and political order was firmly committed to the institution of slavery. Irish immigrants had to adapt to the reality of the southern racial order to advance their own economic prospects, but not all immigrants adhered to southern social norms. Patrick Lynch married Catherine White, a mulatto slave on the plantation. Their marriage was not legally recognised. Louisiana state law also ruled that the children of a slave mother were slaves, regardless of paternity. John Roy Lynch was half-Irish and all slave.

In order to emancipate his family, Patrick had to become their legal owner. He succeeded in purchasing his family but state law required that any master who sought to free a slave had to post a bond of $1,000 to ensure that they would not become a public charge; thereafter the emancipated slave had a month to permanently leave Louisiana. Before Patrick Lynch could raise the bond money, the Tacony plantation was sold to Alfred V. Davis, who refused to retain the Irishman as the overseer. Patrick convinced Davis to allow his family to remain on the plantation until he could relocate them. He travelled to New Orleans in search of employment but was soon taken ill. Against the advice of his physician, Patrick returned to his family before he passed away on 19 April 1849. On his deathbed Patrick arranged for a close friend, William G. Deal, to take title of Catherine and her children. Deal became their legal owner and swore to treat them as freed people. He betrayed the family, however, and sold them to Davis, who moved the family to his holdings in Natchez, Mississippi. John Roy Lynch was two years old when his father died. Reflecting years later, John believed that his father ‘had done all for his family that it was possible for him to do’. As an enslaved child, John was trained as Davis’s personal valet, but as a teenager he worked in the cotton fields. John remained a slave until he was sixteen, when Union forces occupied Natchez in 1863.

Once freed, Lynch performed a series of odd jobs before ‘an intimate friend of my father’, Patrick H. Graw, an Irishman, secured him a position in a Natchez photography firm. Lynch believed that this ‘marked the beginning of a somewhat eventful career’. By 1866 he was manager of the shop. Determined to acquire an education, he attended night schools operated by northern schoolteachers. In 1868 he became involved in the local Natchez Republican club. He quickly earned a reputation as a first-rate public speaker and distinguished himself as a community leader. In April 1869 the military governor of Mississippi, Albert Ames, appointed Lynch justice of the peace for Natchez. His appointment was greeted with disdain by the local Democratic newspaper: ‘We are now reaping the ravishing fruits of Reconstruction’. Lynch seized the new opportunities emerging for African-Americans during the Reconstruction era. Before the year was out, he secured his first elected office, winning a seat in the Mississippi State House of Representatives. Lynch distinguished himself as one of the state’s leading Republican leaders. In January 1872 he was selected as the first black Speaker of the House and in that same year he was elected to the US House of Representatives. At the close of the 1873 session, the lower house of the Mississippi legislature adopted a resolution thanking the speaker and congressman-elect for presiding ‘with becoming dignity’ and ‘with marked ability’.

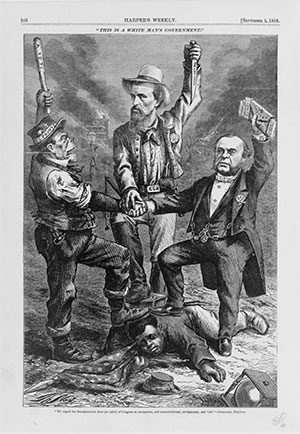

Above: ‘THIS IS A WHITE MAN’S GOVERNMENT’, by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, 5 September 1868. Depicted trampling a black Civil War veteran are a ‘Five Points Irishman’, Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest, and Wall Street financier and Democratic Party chairman August Belmont. The three figures represent the core pillars of the Democratic Party. The caption reads: ‘“We regard the Reconstruction Acts (so called) of Congress as usurpations, and unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void.”—Democratic Platform.’ (Library of Congress)

When the 43rd US Congress (1873–5) convened, Mississippi’s first black congressman, 26-year-old John Roy Lynch, was its youngest member. Lynch actively advocated for the passage of the 1875 Civil Rights Bill, which outlawed racial discrimination on public transport and in public accommodations. Drawing on his own personal experience, Lynch informed Congress that, as a Congressman travelling on public trains, ‘I am treated not as an American citizen, but as a brute … simply because I happen to be of a darker complexion’. If such discrimination continued to be tolerated by Congress, Lynch declared that ‘I can only say with sorrow and regret that our boasted civilization is a fraud; our republican institutions a failure; our social system a disgrace; and our religion a complete hypocrisy’. The Civil Rights Bill was successfully passed by Congress and signed into law on 1 March 1875 by President Ulysses S. Grant.

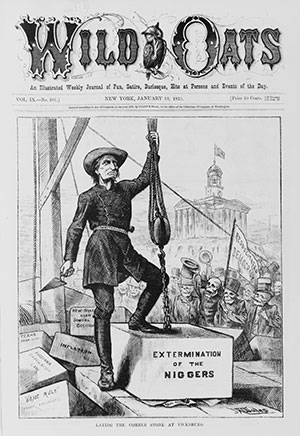

Above: ‘LAYING THE CORNER STONE AT VICKSBURG’, by James A. Wales, Wild Oats, 13 January 1875. A man representing the ‘White League’ lays the cornerstone of ‘EXTERMINATION OF THE NIGGERS’ before a crowd of skeletons representing ‘RESUSCITATED DEMOCRACY’. In 1874, armed members of the White League seized control of elections in Vicksburg, Mississippi. The cartoon foreshadowed the violence of the ‘Mississippi Plan’. (Library of Congress).

When Lynch returned to Washington for the 44th Congress (1875–7), the House for the first time since the Civil War was controlled by the Democrats. Lynch spent much of his term speaking out against the injustices in Mississippi. The electoral districts in Mississippi were gerrymandered to ensure a Democrat majority. Lynch represented the sixth district, which became known as the ‘shoestring district’ after the boundaries were redrawn. The sixth district hugged the Mississippi River counties, squeezing the majority of the state’s black voters into a single district. By the end of 1875, Lynch noted that ‘the political clouds were dark’. He suffered his first electoral defeat in the 1876 Congressional election. He was defeated by the Democratic candidate, James R. Chalmers, a former Confederate general who had participated in the indiscriminate massacre of African-American soldiers at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, in 1864. Lynch contested the election results on the grounds that the contest was marred by violence and fraud. Congress and the Committee on Elections were dominated by the Democrats, who refused to hear Lynch’s case. The following year, the death-knell sounded for Reconstruction as a result of the disputed 1877 presidential election. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was eventually awarded the presidency after a compromise that acknowledged the legitimacy of Democratic-controlled southern legislatures.

Despite the betrayal of black Republicans, Lynch remained active in politics. In 1880 he challenged Chalmers in the congressional election. The contest attracted widespread attention. On 27 October 1880 the New York Times reported that Chalmers was a man who ‘used every means in his power to keep the black men down. He has been indirectly the cause of many of the outrages committed against them.’ Indeed, Lynch was considered ‘a brave man. He freely proclaims his Republicanism and his devotion to the work of elevating the freedmen and bettering their condition.’ Chalmers was once again declared the winner and Lynch protested the result. This time, however, after lengthy deliberation, the House Election Committee ruled that Lynch should be awarded the seat to the 47th Congress (1881–3) and voted to de-seat Chalmers. This was a rare win for Republicans in the post-Reconstruction South. Lynch failed to be re-elected in 1882 and made two more unsuccessful bids for Congress in 1884 and 1886.

Lynch viewed himself as a southern Republican. He did not use his Irish ancestry as a political asset. He was aware that the small Irish population of Mississippi favoured the white supremacists of the Democratic Party. In his autobiography Lynch recorded an encounter in a St Louis hotel where the Irish staff refused to serve him. Lynch informed them ‘that though a colored man, I was of Irish descent’. The staff were ‘considerably amused’ by this fact and treated Lynch with respect for the remainder of his stay. Lynch’s opponents used his mixed lineage to attack his personal character. For example, in the 1880 election the Democratic press attacked ‘the prominent yellow Republican leaders of this state’ such as Lynch, whose white parentage gave ‘the negro race more low cunning, and what may be called “smartness”, than it does wisdom or any sense of honor’. Nevertheless, Lynch persevered and in 1884, as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago, he was elected the temporary chairman of the convention. It was the first time that a black politician delivered a keynote address before a major political convention in the US. In 1885, as chairman of the Republican Executive Committee for Mississippi, he outlined the dire political circumstances: ‘it is a fact known to all that we no longer enjoy the privilege of having popular elections … Our present pretended state government was brought into existence and is maintained through usurpation, violence, and fraud.’ In 1889 President Benjamin Harris rewarded Lynch for his loyalty to the Republican Party by appointing him as fourth auditor of the United States Treasury.

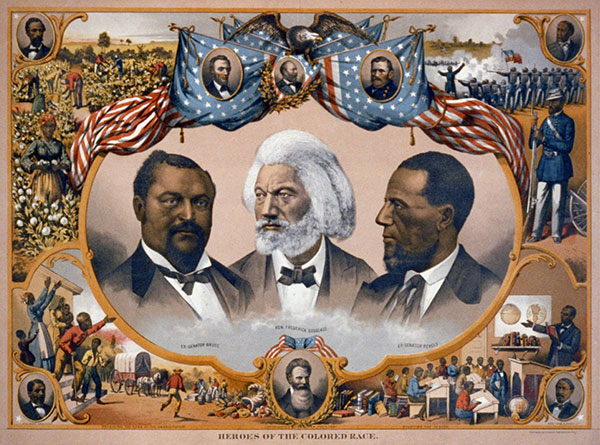

Above: ‘HEROES OF THE COLORED RACE’—Blanche Bruce (US Senator, Mississippi, 1870–1), Frederick Douglass and Hiram Revels (US Senator, Mississippi, 1875–81). They are surrounded by scenes of African-American life and portraits of leading abolitionists and Republican politicians. John Roy Lynch is in the top right-hand corner. (Library of Congress)

Life outside representative politics

In 1884 Lynch married Ella Sommerville. The couple had one daughter, Alice. They later divorced in 1900. During the 1890s Lynch studied law and was admitted to the Mississippi bar in 1896. Following the outbreak of the Spanish–American War of 1898, President William McKinley appointed Lynch paymaster of volunteers in the US Army. After the war, Lynch remained in the regular army and was promoted to the rank of major. He served tours of duty in the Philippines, Cuba and Hawaii. During these tours he met Cora Williamson, whom he married after he retired from the army in 1911. The 1890s witnessed the widespread imposition of segregation in the South following the 1883 Supreme Court decision to invalidate the Civil Rights Bill of 1875. The newly-wed couple settled in Chicago, where Lynch established a law practice.

At the turn of the twentieth century the Dunning school dominated academic as well as public interpretations of Reconstruction. Pioneered by Columbia University historian William A. Dunning and his students, their analysis was founded on the assumption of ‘negro incapacity’ for government. Lynch believed that such accounts were ‘superficial and unreliable’ and used his own personal experiences to challenge the racist depiction of inept African-American politicians. In 1913 he published The facts of Reconstruction, one of the first works to challenge the popular consensus that Reconstruction was a national tragedy. For Lynch, Reconstruction represented ‘the destruction of the power and influence of the Southern aristocracy’, which produced true democratic governments in the South. Two years after Lynch published his book, the most influential depiction of Reconstruction appeared in D.W. Griffith’s film The birth of the nation. Based on Thomas Dixon Jr’s 1905 novel The Clansman, the film glorified the Ku Klux Klan as saviours of American civilisation. Lynch continued to publish and to challenge ‘false and erroneous opinions’. As a writer he was among the first to provide an African-American counter-historiography of Reconstruction that inspired other scholars. In 1935 W.E. Du Bois offered the first academic critique of the prevailing view of Reconstruction in his masterpiece Black Reconstruction in America. Du Bois acknowledged Lynch’s influence and the two men maintained cordial correspondence. Nevertheless, it was not until the 1960s, when the edifice of the Jim Crow South began to collapse, that the wider American public began to discover the facts of Reconstruction. In 1939, at the age of 92, Lynch passed away while completing his autobiography. He was buried with full military honours in Arlington National Cemetery.

Joe Regan is a history Ph.D graduate of the National University of Ireland, Galway.

Read More:

Reconstruction

FURTHER READING

Behrend, ‘Facts and memories: John R. Lynch and the revising of Reconstruction history in the era of Jim Crow’, Journal of African American History 97 (4) (2012), 427–48.

Franklin (ed.), Reminiscences of an active life: the autobiography of John Roy Lynch (Chicago, 1970).

J.R. Lynch, The facts of Reconstruction (New York, 1913).