‘Guardian of the shore’: Seán D. Dublin Bay Loftus and community politics

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Volume 25AFTER THE FORMATION LAST YEAR OF A GOVERNMENT INCORPORATING INDEPENDENT MINISTERS AND RELIANT ON INDEPENDENT TDS TO AN UNPRECEDENTED EXTENT, IT MAY BE OF INTEREST TO LOOK BACK ON A CELEBRATED INDEPENDENT COUNCILLOR AND TD WHO DECIDED THE FATE OF A GOVERNMENT

By Patrick Maume

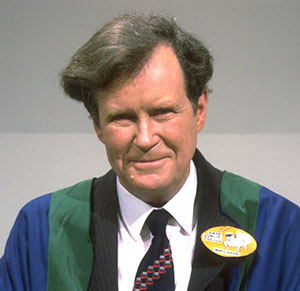

Above: Alderman Seán D. Dublin Bay Rockall Loftus during the 1984 European elections. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Early life

Seán Daniel Loftus was born in Dublin in 1927, son of a Mayo-born doctor. (Loftus mentioned his Mayo antecedents so often that some commentators believed that he was born there.) After two unhappy years as a medical student in UCD, Loftus went to London in 1946 and worked on building sites on the South Bank. Eighteen months later he returned to Ireland to be treated for tuberculosis, then worked on a nuclear power station in Essex, returning to Dublin in 1952. The building sites gave Loftus an awareness of the importance of town planning, a belief that he understood the Irish diaspora and a desire to remake Ireland so that emigration would become unnecessary.

Seeking political training, Loftus studied law at King’s Inns and was called to the bar in 1958. He flirted with the right-wing group National Action, which advocated the abolition of political parties, election of the Dáil on a non-party basis and vocational government.

In 1958–61 Loftus visited the United States as a travelling lecturer on Irish matters, learning more about the Irish diaspora and American publicity techniques. He developed an interest in the environmental movement after seeing carrots grown in a test-tube and touched up with orange paint at an agricultural show.

Back in Ireland, Loftus practised as a barrister (1961–6). In 1966 he became a lecturer in planning law at Bolton Street College of Technology, holding this post until retirement in 1991. Thereafter he rarely appeared at the bar, except to represent himself or environmental groups before planning inquiries or to lodge court appeals against aspects of public policy. During the 1960s he joined protests against the demolition of Georgian houses on Hume Street and redevelopment in the Liberties.

Around 1962 Loftus married Una Fitzsimons, a teacher and Irish-language activist; they met at a social event where she addressed him in Welsh because he was wearing a Red Dragon badge to indicate support for the Welsh nationalist party, Plaid Cymru. They had a son and two daughters. The family lived in a flat in the Liberties (1962–8) before moving to Seafield Road in Clontarf, where they spent the rest of their lives. They were a close and affectionate family; Una’s organisational abilities played a vital role in Seán’s political activities, and Seán thanked her in his 1981 Dáil maiden speech.

Christian Democratic Party

In May 1961, just before returning to Ireland, Loftus announced the formation of the Christian Democrat Party of Ireland (CDP). The CDP advocated social and economic regeneration of Ireland on Catholic principles through implementing the report of the 1943 Committee on Vocational Organisation (involving reconstitution of the Senate as a fully independent chamber elected by unions and trade associations, allowing non-party experts to serve in government) and removal of the preamble to Article 45 of the Constitution (making social rights fully justiciable; Loftus later claimed that this would assist planning by balancing developers’ property rights with social justice concerns). Loftus favoured the popular initiative referendum to bypass the policy-making stranglehold of political élites, a two-seat Dáil constituency representing emigrants (to be granted postal votes), and an ombudsman to address individual grievances (as implemented twenty years later). He believed that Irish banks should be constrained by the general good rather than simple profitability, and accompanied aggrieved debtors to bank AGMs.

The CDP was a support group for Loftus’s Dáil candidacies; Loftus was always better at proposing ideas, ranging from the brilliant to the absurd, than at compromise or coalition-building—a campaigner rather than an administrator. (One other CDP candidate, Daniel McCarron, contested Donegal North-East in 1973 and Dublin South Central in 1981.) In 1965 the CDP sought inclusion on the Register of Political Parties, but was rejected as it lacked coherent structures. Loftus contested the Dublin North-East Dáil constituency in 1961, 1963 (by-election), 1965 and 1969 using the Christian Democrat title, though it did not appear on ballot papers. Although he polled over 1,000 votes in his first three contests, his vote noticeably declined in 1969 and in 1973 (in Dublin North Central).

Seán D. Christian Democrat Dublin Bay Loftus

During the 1973 general election, Loftus changed his name by deed poll to become Seán D. Christian Democrat Dublin Bay Loftus. (During the campaign he walked around with a sign reading ‘Mr Dublin Bay’ pinned to his clothes.) He removed ‘Christian Democrat’ from his name before contesting the 1974 elections for Dublin City Council, saying that party politics should be excluded from local government.

‘Dublin Bay’ highlighted his opposition to certain proposals to redevelop the bay area—particularly a request (1972–6) by a shell company (backed by the French state oil company and unidentified Irish businessmen) to build an oil refinery beside Poolbeg power station. Almost immediately he became widely known as ‘Dublin Bay Loftus’. Before cheap air travel, the beaches of Dublin Bay were the principal recreational amenity for most of the city’s population. (The Loftuses liked to stroll down the North Bull island; Una swam while Seán combined nature observation with the children and pointing out where raw sewage was pumped into the bay.)

Above: Loftus as lord mayor of Dublin on the podium at College Green with US President Bill Clinton and his wife Hillary during their visit to Ireland in December 1995. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Loftus’s campaign against the refinery proposal led to his election to Dublin Corporation in a loose alliance of independents, the Community Government Association. He was returned at every local election until his retirement in 1999, becoming an alderman in 1979 and lord mayor in 1995–6. This electoral record was all the more impressive because his views of constituency work were eccentric by Irish standards and he was willing to support unpopular proposals in the public interest, such as the construction of a private toll bridge across the Liffey to reduce congestion. Loftus’s characteristic campaign tactics included verbose newspaper advertisements, chain letters and appeals to supporters to organise impromptu collections to replenish his ‘Politico-Environmental Bank Account’, which defrayed the costs of campaigns and court actions. (Loftus lived modestly—he could not afford a car—and his campaigns involved financial sacrifice.)

Social conservative

The political and constitutional preoccupations of his Christian Democrat era recurred throughout his later career. Loftus was active on the conservative side in the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s (he opposed the 1972 removal of the special status of the Catholic Church from the Constitution, campaigned for the 1983 Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, opposed the legalisation of divorce, predicted that liberalising the law on contraception would create ‘total promiscuity’, advocated a referendum to overturn the partial legalisation of abortion by the 1992 ‘X case’, and supported the independent ‘family values’ presidential candidate Dana Rosemary Scallon in 1997), but his election to Dublin Corporation in 1974 marked a watershed in his career and associated him with the environmental campaigns for which he is chiefly remembered.

In 1978 Loftus added ‘Rockall’ to his name (he argued that asserting an Irish claim to the mineral resources of a 200-mile economic zone around the islet could transform the Irish economy, North and South). After being elected an alderman he added ‘Alderman’ to gain a higher place on the ballot paper, and during the Wood Quay controversy he added ‘Wood Quay’.

Above: A demonstration at Wood Quay in September 1978. Loftus’s stunts during the Wood Quay campaign included showing a finger-bone from the site to Queen Margrethe of Denmark when she visited Ireland.

Loftus’s campaign against the refinery (rejected after a 1976 public inquiry which Loftus presented with a bucketful of sewage from the bay) was supported by numerous community groups but opposed by Official Sinn Féin (OSF), who thought an indigenously controlled refinery vital for Irish industrialisation and a counterweight to oil multinationals. Two of RTÉ’s Seven Days programmes (in 1975) were accused of caricaturing Loftus, of pro-refinery bias and of being unduly influenced by OSF; Loftus replayed a Seven Days programme at the inquiry with a running commentary on its alleged distortions, and regularly accused RTÉ (in contrast to national newspapers) of bias against him. OSF members denounced Loftus as representing well-heeled suburbanites such as members of the Clontarf Yacht Club at the expense of unemployed inner-city workers; Loftus replied that he had never been on a yacht in his life, that he was defending amenities for ordinary people, and that the refinery would have been controlled by a French multinational and would have provided little employment.

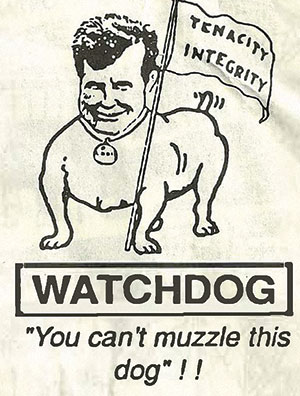

Above: His trademark ‘terrier’ symbol, originally drawn for him in 1977 by the former Dublin Opinion editor Charles E. Kelly. (Irish Election Literature)

Loftus also mounted a long-running campaign to make a Special Amenity Order covering Dublin Bay. He regularly urged Dublin Corporation to use its presidential nomination powers: in 1974 he sought to nominate Rita Childers to complete her husband’s presidential term; in 1976 he ran a ‘draft Ó Dalaigh’ mass letter-writing campaign to persuade Cathal Ó Dalaigh to renominate himself; and in 1990 he tried to get the Corporation to nominate Community councillor and former lord mayor Carmencita Hederman.

Elected TD

In the 1981 general election, despite division of his Clontarf stronghold between two new constituencies and a low first-preference vote, Loftus won the last seat in the four-seat Dublin North-East constituency. With independent and small-party TDs holding the balance of power, unsuccessful overtures were made to Loftus to become Ceann Comhairle. Loftus’s parliamentary speeches were rambling and unfocused, and his failure to gain concessions from the Fitzgerald government for his constituents contrasts with Tony Gregory in the next Dáil. Whereas Gregory set long-term ideological views aside to secure concrete achievements through a binding deal, Loftus voted as he chose while repeatedly—and unrealistically—advocating a national government to address Ireland’s economic problems.

(During the 1961–5 Dáil Loftus denounced Independent TD Frank Sherwin for sustaining a minority government in power.) Perhaps he might have been happier with Fianna Fáil, given his views on Northern Ireland—he was an outspoken supporter of the H-Block campaign—and his denunciation of Garret Fitzgerald’s ‘constitutional crusade’ as an attempt ‘to deChristianise the people’s constitution’, but some of his most outspoken Corporation opponents were Fianna Fáil councillors such as Seán Moore and Ned Brennan.

On 27 January 1982 the government fell after Loftus and Jim Kemmy voted against its budget over proposals to increase taxation on clothing and footwear; as the last TD through the lobby, Loftus’s vote was decisive. Up to the last minute Fine Gael TDs who knew Loftus from Dublin Corporation tried to persuade him to change his mind; although Loftus knew that an early election would endanger his seat, he refused to budge without assurances from Garret Fitzgerald, who was preoccupied with Kemmy. Fine Gaelers denounced Loftus’s action as irresponsible. Loftus consistently denied claims by Fitzgerald that he had not made his intentions clear, claiming that he had stated that he could not vote to sacrifice Irish textile and footwear jobs and that he would have voted for the government if it had withdrawn the offending proposals, as it did during the subsequent election campaign. (Fitzgerald’s misjudged concentration on Kemmy rather than on the possibly more malleable Loftus may have reflected the fact that Kemmy had hitherto supported the government, as well as the unrealistic nature of some of Loftus’s suggestions; he had urged Fitzgerald to impose protective tariffs—illegal under EEC regulations—to defend Irish clothing and footwear.)

Loftus promptly sent a message to President Hillery, urging him to refuse a dissolution and promote the formation of a national government; he publicly denounced Hillery’s failure to accept this advice. Loftus contested Dublin North Central as well as North-East, and was beaten in both. Although he contested North-East in November 1982 and North Central in 1987, 1989, 1992 and 1997, Loftus never again became a TD. Transfer patterns show that his votes came from across the political spectrum and were truly personal.

‘The first Green’

After retiring from Dublin Corporation in 1999, Loftus remained active in local community groups and co-founded (1999) Dublin Bay Watch, which campaigned successfully against proposals by the Dublin Port Company to reclaim 52 acres of Dublin Bay. In his last years Loftus (who sometimes called himself ‘the first Green’) shared platforms with Green Party public representatives. Some of his constitutional proposals, such as the initiative referendum and postal votes for emigrants, were taken up by the Greens and other protest groups.

Loftus died in the Mater Hospital, Dublin, on 10 July 2010, and at his funeral was hailed as ‘guardian of the shore’. His daughter Muireann declared that he had taught how ‘one man standing alone can make a difference’.

Patrick Maume is an editorial assistant with the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

FURTHER READING

V. Browne (ed.), The Magill book of Irish politics (Dublin, 1981).

D. McIntyre, The meadow of the bull: a history of Clontarf (Dublin, 1987).

Magill: Election ’82 (Dublin, 1982).

S. O’Byrnes, Hiding behind a face: Fine Gael under Fitzgerald (Dublin, 1986).