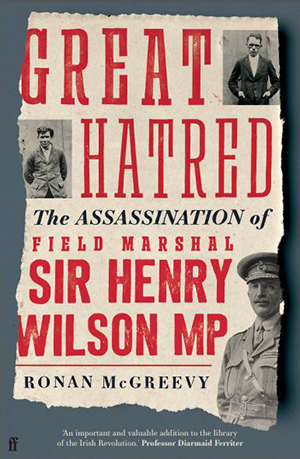

GREAT HATRED: THE ASSASSINATION OF FIELD MARSHAL SIR HENRY WILSON MP

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 3 (May/June 2022), Reviews, Volume 30 RONAN McGREEVY

RONAN McGREEVY

Faber and Faber

£20

ISBN 9780571372805

Reviewed by John M. Regan

Writing in his diary in September 1920, Henry Wilson recorded British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill’s reaction to news from Ireland that ‘Shinners’ were being secretly assassinated by the Crown forces. ‘Winston saw very little harm in it,’ wrote Wilson, ‘but it horrifies me.’ Born in County Longford in 1864, Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) in 1920. Unlike his political bosses—or ‘frocks’, as he famously called them—Wilson apparently remained an obstinate believer in the rule of law. Fearful that republican rebellion would develop into a socialist revolution spreading across the United Kingdom, in 1920 David Lloyd George’s coalition government abandoned the laws and precedents of the British constitution in Ireland. It is, then, interesting to note Wilson’s concern that the State was killing its citizens without recourse to due process. Wilson appeared not to have grasped what Churchill implicitly understood: Ireland was a colonial problem, never a domestic one.

Henry Wilson was a career soldier and a dyed-in-the-wool unionist, who claimed to be an ‘Ulsterman’ on foot of his lineage. He was straight-talking and this trait endeared him to Lloyd George, who enabled Wilson’s promotions towards the end of the Great War. At 6ft 4in. tall, Wilson was noticeable in a crowded street. A nerve severed by the sword of a Burmese ‘bandit’ in 1887 meant that the left side of his face drooped. Apparently, the ‘bandit’ objected to Wilson’s presence in the ‘bandit’s’ country. Wilson liked to tell the story against himself about a letter addressed to ‘The Ugliest Man in the British Army’, which without hesitation or further enquiry was immediately forwarded to him.

Wilson’s military career got off to an unpromising start. He failed five attempts at the army’s entrance examination. Worried about his prospects, his family paid for ‘grinds’, but to no avail. Eventually Wilson entered the army through the back door after four years’ service with the Longford Militia, but he was no dullard and proved himself a very capable officer in the Second Boer War. On his return to England, he was appointed to teaching posts at the staff college at Camberley. A contemporary recalled that Wilson was ‘the most original, imaginative and humorous man … He brought something new … into the discussions of lectures and problems, and his summings-up at conferences’. It was Wilson’s ability to explain complex strategic situations in layman’s terms that so impressed Lloyd George, who said that about Wilson there was none of the pompousness of the officers’ mess. Fellow officers resented Wilson’s political machinations and the rise to high command that they facilitated.

Ronan McGreevy’s much-anticipated study coincides with the centenary of Wilson’s assassination. On 22 June 1922, Wilson was gunned down in front of his wife on the doorstep of his Belgravia home by two IRA volunteers, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan, both later convicted and hanged for the crime. Having recently retired as CIGS, Wilson was a sitting Ulster MP at Westminster and an ‘advisor’ to the Northern Ireland government. To justify his assassination, Wilson has long been vilified in republican lore as the progenitor of the Belfast pogroms in 1920 and as the architect of Northern Ireland’s Special Powers Act in 1922. It remains unclear whether he had hand or part in either.

Wilson’s death hastened events leading to the outbreak of civil war in Southern Ireland. The British government demanded immediate action against the republican faction in Dublin, whom they blamed for Wilson’s death. Rather than risk British military re-intervention, Michael Collins attacked the republican garrison in Dublin’s Four Courts on 28 June, plunging the country into war. Who, if anyone, ordered Wilson’s assassination at such a critical moment in Anglo-Irish relations has remained a mystery that many historians have tried to solve.

McGreevy’s book draws extensively on Bureau of Military History witness statements alongside the more recently released military pension collection, also held in the Military Archives, Dublin. In attempting to attribute ultimate responsibility for Wilson’s assassination, McGreevy offers little that is enlightening. Much of the ‘new’ evidence was well rehearsed in the letters pages of Irish newspapers from the late 1960s, where earlier controversies over Wilson’s assassination long raged.

Many historians have conjectured, as now does McGreevy, that Michael Collins ordered the assassination. Wilson was one among many soldiers and politicians targeted by Collins during the War of Independence and the Truce. Placing Collins in the frame, McGreevy’s evidence is an undated email from a researcher who twenty years ago was briefly given access to a classified document in the Military Archives. The document, which cannot now be located, purportedly identified two of Collins’s men who were involved in Wilson’s assassination. On the other hand, Keith Jeffrey’s exhaustively researched 2006 biography of Wilson concluded that the assassination was most likely the lone initiative of Dunne and O’Sullivan. We will likely never know.

McGreevy’s book is not a work of historical scholarship trying to say something new. Rather it is a historical narrative, telling an engaging story as it tries to unravel the mysteries surrounding Wilson’s death. To those with prior knowledge of Wilson, McGreevy treads all-too-familiar ground with nothing of substance to add. His biographical chapters on Dunne and O’Sullivan are notable exceptions. They are well researched and the most interesting in the book. Both men served in the British army during the Great War. O’Sullivan lost a leg at Ypres in 1917. Dunne’s first choice for an accomplice, Denis Kelleher, made himself unavailable on the day of the assassination. The last-minute decision to murder Wilson was spontaneous and improvised, and turned on an announcement in the press that Wilson would be unveiling a war memorial at London’s Liverpool Street Station.

Dunne and O’Sullivan emerge as committed republicans, both highly intelligent. O’Sullivan was London Irish and was training to be a schoolteacher when he murdered Wilson. Dunne, OC of the London IRA, was a talented musician from a British army family with aristocratic antecedents in County Galway. He memorised operas, which he claimed he could play back in his head while awaiting his execution. Dunne, McGreevy tells us, ‘had the worldview of an English Catholic intellectual, not an Irish revolutionary’. Why these two outlooks are incompatible McGreevy does not say, for Dunne surely reconciled them both. A loner and a committed bachelor, Dunne saw an opportunity to make his mark and hastily recruited O’Sullivan to carry out his half-baked scheme. They had no escape plan—a critical oversight for any one-legged assassin. Chased by an angry mob after the murder, they also shot and injured two policemen and a passer-by.

Extending to over 400 pages, McGreevy digresses into tangential subjects and there is not a little padding. For all the elegance of the prose, this book is an enthusiastic first draft much in need of an editor with a strong historical sensibility. RIC District Inspector Gerald Bryce Smyth was killed by the IRA in Cork in July 1920, and buried at Banbridge, Co. Down. ‘No train driver would transport his body across the border’, McGreevy says, but in July 1920 it is unclear what ‘border’ McGreevy is referring to.

‘The IRA was answerable to Dáil Éireann, the Irish parliament’, McGreevy tells us, and elsewhere he writes of the ‘Provisional Government forces’ in 1922. There is no denying that civil–military relations were complex in the revolutionary period, but it is impossible to understand the origins and development of the new Irish state without coming to terms with those complications. Following interpretations advanced since the 1980s, McGreevy articulates the ‘constitutional interpretation’, asserting that civilian ministers dominated the military. An examination of Eamon de Valera’s failed attempt in late 1921 to fashion the ‘New Army’ from the IRA should disabuse any historian of that view—as would recent historiography.

‘On the evening of 27 June, the Irish cabinet met and decided to act’, observes McGreevy on the decision to attack the Four Courts. Military decisions were made by the pro-Treaty army independently of the civilian governments. The attack on the Four Courts, the introduction of martial law and the official reprisal executions in December 1922 were all exclusively military initiatives. The only government that held sway inside the pro-Treaty army was the Executive of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, over which Collins presided. This kind of criticism could be dismissed as ‘nit-picking’, but misunderstanding civil–military relations has led many historians to obscure the formation under Collins of a military dictatorship from 12 July 1922.

A chapter entitled ‘The madness within’ provides an account of the Civil War, following closely the narrative of the 1998 RTÉ documentary of the same name. ‘Currygrane House [in County Longford, Wilson’s ancestral home] … was burned to the ground by the anti-Treaty IRA in an act of tribal spite in August 1922’, McGreevy says. Later he tells us that it ‘was never established who carried out the attack’, which inevitably raises doubts as to whether ‘tribal spite’ really played a role. Currygrane House, it should be noted, was burned shortly after the execution of Dunne and O’Sullivan in London. McGreevy says that ‘big houses’

‘… were burned in retaliation for the burning of the homes of republicans. Though morally dubious, there was at least a logic to the activities of the IRA in the War of Independence. No such logic attended the burning of 199 big houses during the Civil War, destroyed in retaliation for the executions of republicans. According to [anti-Treaty IRA leader] Liam Lynch, the homes of imperialists were legitimate targets, even if their owners had nothing to do with prosecuting the Civil War.’

Following the logic of McGreevy’s own interpretation, Currygrane House was most likely burned down in reprisal for Dunne and O’Sullivan’s executions.

Almost as an afterthought, McGreevy concedes that ‘Wilson’s blinkered imperialism is shown too in his support for General Reginald Dyer, the perpetrator of the Amritsar massacre’. Without a single mention of his racism or his anti-Semitism up to page 387, Wilson is presented as an affable contrarian. There is no critical discussion of the British Empire or the national liberation struggles that it was confronting by the 1920s. At least 380 unarmed civilians were killed in Amritsar (the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, 13 April 1919), and Dyer later said that, had he the means, he would have killed more. The killing stopped only when his soldiers ran out of ammunition.

Writing to Wilson on 7 July 1920, after the Army Council meeting where Dyer’s case was discussed with Churchill, General Sir Charles ‘Tim’ Harington reported: ‘Winston talked for an hour. He agreed with us [the Army Council] on the necessity to shoot hard.’ By the end of the year Churchill’s words of encouragement resonated throughout Ireland.

If Anglo-Irish policy had been left to him, Wilson said that he would have made no concession to the ‘murderers’ of Sinn Féin. But then again, invading territories and crushing native peoples in the interests of powerful states was the workaday business of empire-builders like Wilson.

John M. Regan lectures in History in the School of Humanities at the University of Dundee.