Giraldus Cambrensis’s view of Europe

Published in Features, Issue 2 (Summer 2000), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 8Giraldus (c.1146-c.1223) is famous, and infamous, for his works describing Wales and Ireland in the later twelfth century: they present both countries from the viewpoint of a Roman-minded Cambro-Norman cleric. However, we also can ascertain his view of Europe through a map that is found in a manuscript along with his two books on Ireland—the Topographia Hiberniae and the Expugnatio Hibernica—now in the National Library, Dublin (MS 700). Giraldus himself is one of the more colourful clerics of the period. Born in Pembrokeshire in 1146, he was both Welsh and Norman. Educated in Paris as a young man, he returned (1175) to Wales in the hope of becoming bishop of St David’s. He entered Henry II of England’s service in 1184 and it was in connection with this that he wrote his two books on Ireland. In 1188 he preached the crusade alongside the Archbishop of Canterbury in Wales and this led to his two books on Wales. In 1199 he was again elected by the chapter of St David’s as their choice for bishop, but this was neither to the king’s nor the Archbishop of Canterbury’s liking, and so began four years of bitter legal disputes between Giraldus and the archbishop in order to obtain the see. In pursuit of his case Giraldus travelled on three occasions (1199, 1201, and 1203) to Rome, but eventually acknowledged defeat. The last twenty years of Giraldus’s life (he died in 1223) are obscure: we know that he was reconciled with the archbishop, that he continued his literary pursuits, and that he made a final trip to Rome in 1207 as a pilgrim.

The manuscript

What evidence is there linking the map to Giraldus? Does its location in the manuscript provide us with clues to its purpose? While it is found in the same manuscript volume as both of Giraldus’s works on Ireland, it is actually a distinct work for it is found between them (not in either) in the manuscript. It is reasonable to argue, therefore, that it was planned with the rest of the volume from the outset, and that that volume was originally made for Giraldus.

In his edition of the Expugnatio, Brian Scott has dated it on textual and palaeographical grounds to around 1200, and he put it in the immediate circle of Giraldus. Given the alterations and additions to the Expugnatio, by the original scribe, then in ‘another…contemporary hand’, and then by a third hand on two added leaves, Scott concluded that the manuscript ‘spent a long time with Giraldus, and [that it was] used by his secretaries to enter in additions to the text of the two Irish works’.

A scribe as represented in Topographia Hiberniae. (National Library of Ireland)

Indeed, the presence of many illustrations and of the map led Scott to hold that ‘this was a manuscript lovingly executed for Giraldus’s own pleasure, then subsequently used to enter later additions and alterations’.

Is the map of Europe on fol. 48r integral to the manuscript or a later insertion. The manuscript contains ninety-nine folios in, as noted, three contemporary hands. The corrections and additions show that it was conceived as a single volume from the outset, as details such as make-up of the quires, ruling, page lay-out, and illuminations make clear. The map is found almost exactly in the middle of the manuscript between the two works. The Topographia ends on fol. 47v (in the left-hand column) and the rest of the page is blank. The map is on the recto (right-hand facing) of fol. 48, and this is followed by a blank verso (left-hand facing). Then, the Expugnatio begins on fol. 49r. However, an empty page at the end of a quire in which a work concludes is not uncommon, and often these blank pages have been filled with miscellaneous items. For the sake of argument, it could be suggested that the map was the work of a later scribe who was taking advantage of an empty folio. However, the similarities of script between the names on the map and the display script in the rest of the volume make this most unlikely. Moreover, the map uses a similar range of colours as was used in both texts.

Conclusive evidence comes from the gutter (the inner margin between two pages) of quire 6. While the page size of the manuscript is 273 x 180mm, and the map takes up the whole width of the page, the map does not run right to the bottom of the page but leaves a 45mm strip blank. Along the other edges of the map (left, top, and right) the green (the colour used for sea) has been brushed out to the edge of the page. Looking at the left margin where the green goes fully into the gutter and binding we find no green marks on the opposite page, fol. 47v,

(National Library of Ireland)

as would be expected were the map a later addition on the spare page. However, on the corresponding page of the bifolium, fol. 41v, the green wash is just visible in the gutter (about 1mm). The absence of green on fol. 47v and its presence on 41v can only be explained if the map was drawn prior to binding. The conclusion that the map is contemporary with the rest of the manuscript volume, or at least with the additional sheets bound in to contain the additions and corrections to the Expugnatio, seems secure. Thus we can ascribe to the map the same date and conditions that Scott has argued for the volume itself. Combining what is known of the manuscript’s origin with the fact that the map is a product of skilled observation and drawing, and knowing Giraldus’s interest in drawing maps and his carefulness as an observer, we can ascribe to him a central role in its creation.

There appears to be no relationship between the map and either text. The map appears to been another distinct work by Giraldus, and placed in this volume with the Topographia and the Expugnatio because this was a book he had prepared for himself. While it has been customary to refer to the map in connection with the Topographia, and to print it with translations of that work, the association is based merely on its presence at the end of that work in this richly illuminated manuscript. Nothing in that text suggests that a map of Europe is required or useful for understanding that text. The map’s connection with Giraldus is not textual, but is dependent on context—on its presence in the volume from the outset, and the volume’s links with Giraldus.

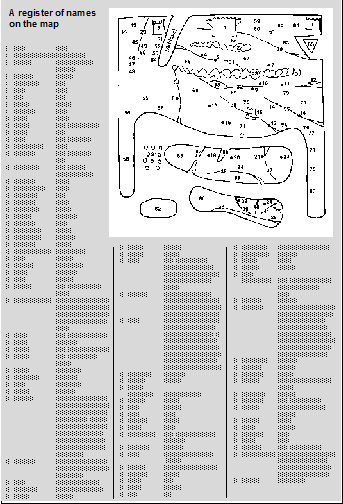

The map

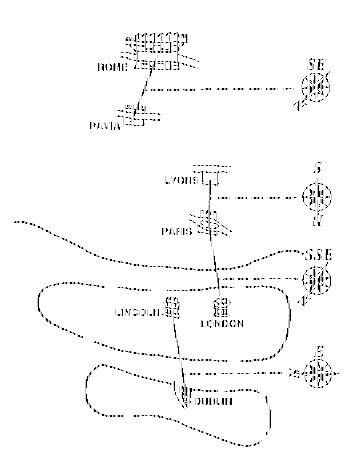

At first sight, the map is a crudely-drawn image of Ireland and Britain almost surrounded by the European land-mass, with south east at the top, and the whole surrounded by water. In contrast to other maps of the time, e.g. the Hereford mappamundi, our map looks like a sketch drawn during a lecture. While the Hereford map shows a variety of features, and gives an impression of realism to coastlines by making them irregular, our map has smooth long curves, and an apparently arbitrary selection of places. Three tightly-spaced Italian cities—Milan [5], Piacenza [4], and Pavia [6]—take up as much space as lies between Paris [16] and Lyon [9]. Elsewhere on the map far less attention has been paid to cities: there are none in Spain [80]

One of the drawings in the margins of Topographia Hiberniae. (National Library of Ireland)

and only Cologne [8] in Germany. The rivers seem to have been drawn with fast strokes of the pen. The map, in short, lacks geographical accuracy. However, the drawing was accomplished with confidence: there is only one place (the line representing the north coast of Spain was originally 18mm longer towards the bottom of the map) where a line was drawn and then corrected by erasure.

If, however, we look at the map’s ‘grammar’—the structures underlying its articulation of the relationship between places—we find that it is quite a sophisticated artefact. Its vertical central axis runs through the British Isles [83-86] at the bottom centre to Rome [1] at the top. It would seem that the chief interests of its creator lay in the prominently drawn British Isles on the one hand, and the connection between those islands and Rome on the other.

The first clue that this is a map of Britain in relation to Rome, as opposed to a geographical map of part of Europe, is the size of the images used to represent the key localities. It is a feature of mental maps that the more significant a place is in the mind of the map-maker, the larger it is represented in proportion to other places. Thus, the British Isles, are equal to over a fifth of all the land shown. Rome is less obviously exaggerated, but the symbol for this city—a crenellated box—is unique on the map. It is also nearly twice the size of the next largest city symbol, used for Constantinople [2], Paris [16], and what was intended to be Reggio di Calabria [3]—the map is damaged there by scraping, and the corner has been damaged by water so that the green pigment has eaten through the parchment. This size-coding of cities raises questions. That Rome should stand out in the map of a medieval cleric is not surprising, nor that Constantinople should be emphasised; their relative sizes are undoubtedly a function of the Roman focus of Latin Christendom and the culture of distinctiveness that we associate with the schism of 1053. Likewise, that Paris should be enlarged is understandable: already in 1200 it was the intellectual capital of the West—Giraldus was an alumnus—and its importance was increasing. But why the emphasis on Reggio? Could it be linked with the fact that this city was captured by the Norman Robert Guiscard in 1060 or is it just an error in cartography? Is it significant that this is the only place-name on the map that is blurred almost to the point of illegibility? No definite answer to any of these questions can be given, but what is certain is that four settlement ranks are differentiated. The highest rank is accorded to Rome alone; Constantinople, Paris, and Reggio follow; the third is comprised by a group of continental cities represented by small crenellated boxes such as those indicating Cologne, Reims [13], Milan, and Pavia; and the fourth is represented by a distinctive sign, a crenellated tower (no smaller, though, than the sign for third-rank places), which is used for the eight towns of the British Isles (four in Britain, four in Ireland). This separateness of the last place-sign would imply that the person who initiated this map had a special interest in these towns in the British Isles as well as in the uniquely important Rome.

A page from Topographia Hiberniae.

A second indicator that what loomed largest in the mind of the map’s creator was the religious and political axis between Britain and Rome is the way information is concentrated into a broad band of land in the middle. Starting at the bottom within this zone we move from the British Isles into France (Francia [70]) whose sub-divisions are named (e.g. Flandria [71], Burgundia [69]), a number of its cities are marked, and three rivers are shown and named. Then the Alpine massif is named. Then comes Italy [67], where both regional and city names are also given. Italy occupies as much of the map as France. Beyond these countries, however, the map-maker’s interest declines—these are peripheral places, mentioned by default. The map really concerns Britain, Ireland, France and Italy. Since, though, the page demands that the surrounding areas be drawn, completeness requires that some details be filled in, giving a context to the map-maker’s principal concerns.

The concentration on lands between Britain and Rome does not mean there was no logic in the arrangement of items on the map’s periphery. Each place on the map is located with reference to the places mentioned which are near it. Beginning with Italy, for instance, it is clear that the Po [31] flows into the Adriatic (not named on the map), on the other side of the Italian peninsula to Rome. Leaving Rome by the Tiber [30] and going first downstream then southwards along the coast to round the toe of Italy, one passes Sicily [65], on one side of the straits, and Reggio [3], on the other. Continuing across the opening of the Adriatic brings one eventually to Constantinople [2], north of which the Danube [29] reaches the sea, as is shown here. All these places are shown correctly in relation to one another (i.e. topologically). Geographically inaccurate as the map may appear to modern eyes, it is by no means an irrational compilation. Time did not affect the medieval cartographer in the way it affects the modern. The map shows information from its own day close to the zone of the maker’s greatest interest (Flanders, Burgundy, and the places emphasised in Ireland), but also information that relates to the distant past near the map’s periphery (the lands of the Goths [44] and the Sigambri [45]).

So what sort of map is it? Although presented as a general map of Europe, it has long been recognised that what we are looking at is a map based upon itineraries from Britain to Rome and to a lesser extent those between important cities within France and Italy. This is confirmed by the map’s orientation, or, more precisely, orientations. Medieval convention placed East at the top of maps, and a quick glance seems to confirm that the convention applies here too: Ireland is shown at the bottom of the map with Britain above it. But there the convention stops. If we examine the orientations in the map’s central zone we find the following sequence. First, a line from Dublin [23] to Lincoln [20] is almost at right angles to the base of the map and does point East. Second, a line roughly parallel to the Dublin/Lincoln one can connect London [21] and Paris [16]. The map’s orientation has shifted to South South-East. Third, after Paris the orientation changes to South as Lyon [9] (very close to South of Paris) is directly above Paris on the map, while the Loire [35], Tours [14], and Angers [18], ranging out to the West, are to the right of a line from Lyon to Paris. Fourth, from Pavia [6] to Rome [1] the orientation is again South-East. These shifts in orientation are consistent with itineraries, or memories of actual travel, being the source of the map of France and Italy.

It is tempting to imagine the routes or travels which might underlie the map, but this would be no more than guesswork. Several possibilities have been offered over the years. A first route might have been one which began at Winchester [22], then following the Seine [36] upstream to Paris [16], thence to Lyons [9], the Alps [28], Pavia [6], Piacenza [4] and through Tuscany [66] to Rome [1]; the second, a route using the Mont Cenis Pass to Susa [7]. My own suspicion, formed principally by the knowledge that earlier ecclesiastics from Britain made use of such a route, is that the route was through Arras [15], Reims [13], Lausanne [33], the Great St Bernard, Pavia [6], and on to Rome. But it is equally clear that the map-maker knew a route from Paris [16] to Lyon [9], and one from Lyon across the Col du Mont Cenis through Susa [7] to Piacenza [4]. In favour of the St Bernard route is the fact that Lake Geneva (Lacus Lemannus is the common Latin name) is labelled Lacus Losanus [33]. Moreover, although mountain peaks are shown on the map (the Apennines [27], most of the Alps [28]) using circular strokes of the pen in black ink, directly above Lacus Losanus mountain peaks are drawn with four straight strokes in the shape of an inverted ‘W’. This probably represents a particular pass, the Col du Grand Saint Bernard.

The shifting orientations of the map are consistent with itineraries, or memories of actual travel.

While we cannot determine the particular itineraries which the map-maker used, we can suppose that the map reflects the route used by Giraldus on his own travels to Rome. Personal recollection may explain why certain places are identified on the map, while others are ignored. If this is the case, then our map is direct evidence to how the journey to Rome was perceived in the British Isles at the time. This information is as important for historians as the information in an itemised itinerary. Thus it is significant that the map portrays the distance from the French coast to Rome as less than that from the south coast of England to the north coast of Scotland. If Rome can be perceived as closer than the length of one’s own island, it is easier for us to understand the number of times clerics took legal cases to Rome, or illustrate the perception of the place of Rome within local church affairs. Put another way, on this map, the journey from St David’s in Wales to Rome is only three times the distance from St David’s to Canterbury; or the distance from Dublin to Rome is just over twice the distance from Dublin to Canterbury. Seen in this way the late-twelfth century disputes about the metropolitan status of the sees of Dublin and St David’s vis-a-vis Canterbury (why neither British see is mentioned on the map is a curious problem), and the raising of these questions in Rome by clerics such as Giraldus, take on a very different complexion. The study of the significance of this map is still in its infancy.

Thomas O’Loughlin lectures in history at Lampeter, University of Wales.

Further reading:

R. Bartlett, Gerald of Wales: 1146-1223 (Oxford 1982).

T. O’Loughlin, ‘An Early Thirteenth-Century Map in Dublin: A Window into the World of Giraldus Cambrensis’, Imago Mundi 51 (1999).

A.B. Scott and F.X. Martin, Expugnatio Hibernica: The Conquest of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis (Dublin 1978).