Gerard Murphy, disappearing Freemasons and the limits of ideological revisionism

Published in Issue 5 (September/October 2017), Platform, Volume 25The Cork Fatality Register for the War of Independence.

By Andy Bielenberg

This multi-year research project has recently been made available on the website theirishrevolution.ie. It has been researched and written by Jim Donnelly and myself; it is run jointly by UCC and the Irish Examiner. The site attempts to document all fatalities in County Cork during the War of Independence, which accounted for about 20% of total deaths in the conflict across the island. These include 49 ‘disappeared’ civilians and members of the Crown forces who were secretly killed and buried by the IRA. The civilian victims include 71 suspected ‘spies and informers’ executed.

While the Cork Fatality Register stops at the Truce of July 1921, we have extended our research further, thus documenting fatalities throughout the Truce down to the end of June 1922. These deaths, on top of the 24 civilians ‘disappeared’ by the IRA in the War of Independence, include eight more civilian disappearances during the Truce period. Details about these ‘disappeared’ in most cases appear in multiple historical sources, which makes it less likely in our view that there are a great number of undocumented disappearances in County Cork, though there are most certainly some. Our preliminary findings also suggest that most of the IRA’s killing of civilian suspects occurred prior to the Truce (rather than after), which follows the wider pattern of fatalities in Cork during the revolutionary period at large. This is also true within Cork city, which saw a number of civilian deaths associated with a so-called ‘Anti-Sinn Féin Society’ in 1920–1. Despite numerous inconsistencies and errors, IRA testimony of this Anti-Sinn Féin group can be broadly reconciled with documented pre-Truce killings (with a small number of exceptions), an area originally researched by John Borgonovo in Spies and informers and the Anti-Sinn Féin Society (2006).

Above: In The year of disappearances Murphy’s thesis is based on a spectacular misinterpretation of the sources.

Above: In The IRA and its enemies Hart’s analysis fails to distinguish adequately between the War of Independence, the Truce and the Civil War, or variable outcomes in the different Cork brigade regions.

My attention was drawn more closely to Murphy’s Freemason list owing to the fact that one entry of our Cork Fatality Register (and also on its precursor, the ‘Cork Spy Files’ database) was proving particularly difficult to identify: Francis McMahon. There was no doubt that a man of this name had been abducted by the IRA on 19 May 1921 and had disappeared without trace (and first identified by John Borgonovo). He was an ex-soldier from the St Luke’s district of Cork city and worked in the Pension Office, and was abducted by the IRA on his way to work. In a blog posting, Murphy pointed out quite correctly that our initial identification of him was incorrect. Instead, Murphy argued that Francis McMahon was actually a Freemason listed as belonging to Lodge 71 in Cork. Murphy still lists McMahon as a Protestant victim of the revolution (blog site accessed 26 July 2017).

Unconvinced, I decided to investigate Murphy’s assertion further. Firstly, Church of Ireland records were consulted at the parish office in Shandon (Cork), with the help of John Mustard. This revealed that a Francis McMahon of 6 Victoria Terrace regularly attended Sunday service at St Luke’s on the north side of Cork city until August 1921. This record was inconclusive, however, as it did not state who in the family attended (his father was also called Francis McMahon). Then Rebecca Hayes, the archivist at the Grand Lodge of Freemasons on Molesworth Street, Dublin, helpfully located the minute book of Lodge 71, which revealed that Francis Victor McMahon of 6 Victoria Terrace, St Luke’s, Cork, was actually still attending Freemason meetings in 1924 and was only struck off the register in 1926. Moreover, probate records show that his father, Francis (who was not a Freemason), died in England in 1925. So it became crystal clear that no Protestant or Freemason called Francis McMahon was ever ‘disappeared’ by the IRA in Cork, despite Murphy’s persistent claims to the contrary.

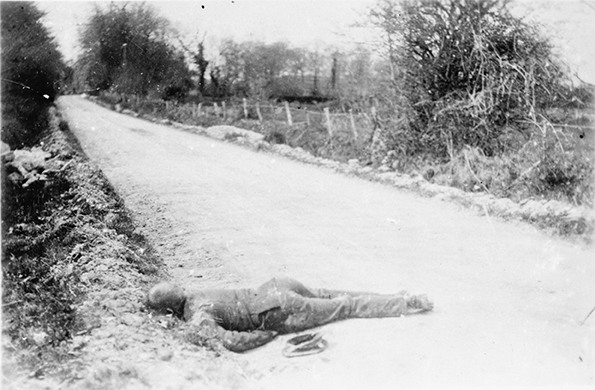

Above: The body of Private Norman Thornton Fielding, 2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment, shot by the IRA in late April 1921 near Liscarroll, Co. Cork. According to the Bureau of Military History witness statement (789, 26) of Denny Mullane (formerly captain of the Freemount Company and also the active service unit of the Cork No. 4 Brigade), ‘On the 25th April, 1921, a British soldier, who gave his name as Private Fielding, and who posed as a deserter from Buttevant Barracks, was captured by Denny Noonan, who was in charge of a party of three, namely, Mick Collins, Con Browne, and Jack Sheahan. He was tried by court martial and executed as a spy in the Charleville Battalion area. Later, I learned from the regiment’s official Lily White Magazine that he was a high ranking, highly efficient intelligence officer. No more would-be deserters visited the area.’ (Imperial War Museum)

Above: Leo (alias Francis) McMahon lived in the St Luke’s district on the north side of Cork city. As a Catholic ex-soldier, he fell within the most typical category of suspects killed by the IRA in County Cork during the War of Independence. This neighbourhood around Victoria Barracks (now Collins Barracks), which also contained four RIC barracks, was regarded as the most hostile area to the IRA in County Cork. According to the Bureau of Military History witness statement (1479) of Seán Healy, captain in A company, 1st Battalion, Cork 1 Brigade, ‘A large percentage of the people in the area had connections with the British forces and police; vested interests had been established over the years; shopkeepers were handling big military contracts; the soldiers and police had intermarried with the citizens; in fact, 90% of the residents in our area could be regarded as definitely pro-British and hostile to the IRA.’ (Martin McMahon and Nickie Cohalan)

Another victim appearing on Murphy’s disappeared Freemason list is John Moore. Murphy declared that Moore was one of two Freemasons whom he was ‘certain’ had been ‘disappeared’ by the IRA in May 1921. Murphy reported that a doddery 70-year-old retired accountant suffering from memory loss left his Friar Street house on 1 May 1921 ‘and was never seen again’ (p. 281). Using a newspaper report of a senile man who had become lost, Murphy curiously conflates him with a struck-off Freemason of the same name, assuming quite wrongly that they were one and the same person. The records of Lodge 71 show, however, that the Freemason named John Moore subsequently took his Grand Lodge certificate examination in October 1921. Unless he rose from the dead, this also conclusively rules out John Moore as having been ‘disappeared’ by the IRA in May 1921, though he still remains on Murphy’s blog list of Protestant victims of the revolution in Cork.

Quite remarkably, Murphy provides little documentary evidence to prove that any of these 32 Freemasons listed were killed. Instead, he argued that they could have been killed, thus shifting the burden of proof to other historians. Murphy was essentially contending that in the year or more after the Truce a sectarian killing event occurred in and around Cork city which was possibly greater in scale than the Bandon Valley killings of April 1922 in West Cork, and that all this had been undocumented and successfully covered up.

Evidently it did not occur to Murphy that a potentially fruitful line of inquiry to test his somewhat speculative theory, before going to press, would have been to see who on his Freemason list was still living after the revolution. Fortunately, Barry Keane has done just that. Accessing various genealogical records, he determined that the great majority of the 32 missing Freemasons listed by Murphy definitely survived the revolution.

While there is no doubt that Freemasonry was viewed with deep suspicion by the Cork IRA, who killed at least two members between 1921 and 1922, Murphy’s assumption that there was some kind of major Freemason-killing event was essentially a piece of creative speculation. The preface of his book reveals that it started out as a work of fiction before being transformed into a work of non-fiction; aspects of the book evidently never quite made the necessary transition. Murphy’s thesis that a substantial number (e.g. scores) of undocumented disappearances (notably of the anti-Sinn Féin spies and informers and Freemason variety) occurred in the year or more following the Truce is essentially based on a spectacular misinterpretation of the sources. His bogus conclusions give further succour to a misplaced school of thought that the most noteworthy feature of the revolution in Cork was the sectarianism of the IRA.

It will come as no surprise that Eoghan Harris in his column in the Sunday Independent remains an ardent supporter of Murphy’s analysis in The year of disappearances. Its Gothic appeal, however, does not extend to historians, who have slated it in damning reviews. Most historians of the Irish revolution (who research and assess actual evidence) have moved on from the toxic legacy of the Northern Irish troubles, which has cast a long enough shadow over the discipline.

Andy Bielenberg is a Senior Lecturer in history at University College Dublin.

FURTHER READING

A. Bielenberg & J. Borgonovo, assisted by J. Donnelly, ‘“Something of the nature of a massacre”: the Bandon Valley killings revisited’, Eire-Ireland 49 (Fall/Winter 2014).

A. Bielenberg & J. Donnelly, ‘Cork Fatality Register’, www.theirishrevolution.ie.

J. Borgonovo, Spies and informers and the Anti-Sinn Féin Society (Dublin, 2006).

P. Hart, The IRA and its enemies: violence and community in Cork 1916–1923 (Oxford, 1998).

B. Keane, ‘The undead: Ireland’s War of Independence and Cork’s Freemasons 1920–1926: 31 May 2017: a final reply to Gerard Murphy’,

http://www.academia.edu/7645467/The_Undead_Irelands_War_of_Independence_and_Corks_Freemasons_19201926_31_May_2017_A_final_reply_to_Gerard_Murphy.

G. Murphy, The year of disappearances: political killings in Cork 1921–1922 (Dublin, 2011).

P. Ó Ruairc, ‘Spies and informers beware’, History Ireland 25 (3) (2017).