‘Geographical loyalty’? Counties, palatinates, boroughs and ridings

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2012), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 20

Seánie Johnston playing for his native Cavan. (Anglo-Celt)

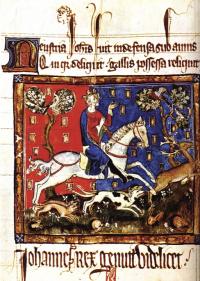

Fourteenth-century depiction of Prince (later King) John, who started the process of shiring while lord of Ireland (1185–1216) with the creation of County Dublin in the 1190s. (British Library)

Liberties and palatinates

In the early stages of Anglo-Norman expansion in Ireland, liberties or palatinates were larger and more numerous than counties. These were counties enjoying special autonomy under the government of a great lord, largely independent of the Crown and generally situated in peripheral or frontier regions. In Ireland it suited the English Crown, preoccupied elsewhere, to delegate the conquest and government of the country to great lords. The first to be created were Leinster (roughly equivalent to the southern half of the modern province) for Strongbow around 1172, Meath (roughly equivalent to the northern half of modern Leinster) for Hugh de Lacy in 1172 and Ulster (which encompassed the modern counties of Antrim, Down and northern Derry) for John de Courcy later in the 1170s. There was also a short-lived liberty of Thomond (1276–87), equivalent to the modern County Clare, granted to Thomas de Clare (who, interestingly, gave his name to the county) but only for his lifetime.In the 1240s the liberties of Meath and Leinster were both partitioned. The death of Walter de Lacy without a male heir in 1241 resulted in the division of Meath into two liberties, one of which first became part of County Dublin (1280) and then the newly created county of Meath (1297), while the other eventually passed by inheritance to the Crown in 1461 and was abolished in 1479. Leinster passed by marriage to the Marshal family, earls of Pembroke, whose extinction in 1245 resulted in its partition into four liberties—Wexford, Carlow, Kilkenny and Kildare. Of these, Kildare became a county in 1297, again a liberty (1317–45) and permanently a county in 1345. Carlow became a county in 1306, a liberty again (1312–44) and a county permanently in 1344. Kilkenny became a county between 1396 and 1402 (though in reality under the earls of Ormond it was to enjoy the autonomy of a liberty for centuries thereafter), while Wexford only became a county in 1536. The liberty of Ulster reverted to the Crown in 1461 and was extinguished around 1482.In the fourteenth century there was a second wave of liberty creation. Louth was a short-lived liberty (1318–28), created first for Sir John de Bermingham and then for Roger Mortimer, earl of March (1330). By contrast, two very long-lived liberties were established at this time: Tipperary for the Butlers, earls of Ormond (1328), and Kerry for the Fitzgeralds, earls of Desmond (1329). Both were to be abolished and replaced by their respective counties as a result of their holders’ involvement in rebellions—Kerry (1579) at the outset of the Desmond Rebellion and Tipperary (1716) after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715.

Sixteenth-century depiction of Hugh de Lacy, who in 1172 was granted the liberty of Meath (the northern part of the modern province of Leinster). It suited the English Crown to delegate the government of such frontier regions to great lords. County Meath was created in 1297, Westmeath in 1541–2 and Longford in 1570. (British Library)

Second wave of county creation

The Gaelic Irish made a remarkable recovery in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and the lordship of Ireland fragmented into a mosaic of lordships that gradually achieved de facto independence. This resulted in the effective collapse of many of the counties and liberties created in the thirteenth century. By 1520 only Dublin, Louth, Kildare, Meath (all in the Pale) and Limerick, plus the liberties of Kerry, Tipperary (including the nominal county of Kilkenny) and Wexford, still functioned. The Tudor conquest (1534–1603), however, resulted in the second and most lasting wave of shiring in Ireland. This was a twofold process. First, the twelve counties of medieval origin (Louth, Meath, Dublin, Kildare, Carlow, Wexford, Kilkenny, Tipperary, Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Kerry) were invigorated in some cases and revived in others. Second, twenty new counties were created. In 1541–2 Westmeath was separated from Meath, and Queen Mary’s plantation of the midlands in the 1550s was accompanied by the creation of King’s County (Offaly) and Queen’s County (Laois) in 1557. The process culminated in 1570, when the defunct county of Connacht was divided into Galway, Mayo and Sligo; Roscommon was revived; Clare was created and temporarily moved from Munster to Connacht (until 1602); Longford was established; and Antrim and Down were erected on the ruins of the old earldom of Ulster. In 1583 Leitrim was separated from Roscommon. Ulster was the last province to be shired, in two stages: nominally in 1585, when Donegal, Coleraine (later Derry and Londonderry), Tyrone, Armagh, Fermanagh, Monaghan and Cavan were established, and actually after 1603, when effective English rule was established over the whole country for the first time. The last county to be created was Wicklow in 1606. There were also two ephemeral counties: Ferns in north Wexford (1579–86) and Desmond in south Kerry (1571–1606).

The medieval, modern and urban counties of Ireland. (Tomás Ó Brógáin)

Urban counties

Since 1412 a total of ten Irish urban areas have gained county status in their own right. Before 1412 Drogheda had consisted of two distinct boroughs divided by the River Boyne, the northern in Louth and the southern in Meath. In 1412, Henry IV issued a charter uniting them into one borough, which was granted county status and full independence from both counties. Drogheda was followed by Dublin (1548), Carrickfergus (1569), Waterford (1574), Cork (1608), Limerick and Kilkenny (both 1609) and Galway (1610). There were no further creations until 1899, when the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898 gave county status to Belfast and Derry and removed it from Drogheda, Kilkenny, Galway and Carrickfergus. Subsequently, Belfast and Derry ceased to be counties in 1973, but Galway’s county status was restored in 1986. Currently five Irish urban areas (all in the Republic) enjoy county status. Finally, some of the canonical 32 counties have been partitioned. In the nineteenth century three Irish counties were divided into ridings, a subdivision particularly associated with Yorkshire. In 1823 Cork was divided into an East and West Riding for judicial purposes only, while in 1837 Galway was divided into East and West Ridings for the appointment of county surveyors and the management of the police force. Each retained a single grand jury (an unelected committee of 23 individuals, usually wealthy landowners, chosen twice yearly by the sheriff to perform both administrative and judicial functions) and after 1899 a single county council. By contrast, when Tipperary was divided into a North and South Riding in 1838 each was given a separate grand jury, which resulted in their becoming fully fledged administrative counties, a status they continue to enjoy. On the other hand, the ridings in Cork and Galway did not develop into administrative counties and became obsolete after independence. The late twentieth century saw further adjustments to Ireland’s counties. Under the provisions of the Local Government (Northern Ireland) Act of 1972, the traditional six counties plus Belfast and Derry lost county status and were replaced by 26 district councils with very limited powers. In the 1990s the rapid growth in the population of Greater Dublin resulted in the partition of the ancient county of Dublin into three new administrative counties: Fingal (administrative centre Swords), Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown (administrative centre Dún Laoghaire) and South Dublin (administrative centre Tallaght), with effect from 1 January 1994. The city of Dublin remained unaffected and retained its status as an administrative county.

The forging of county identy

John A. Murphy once wrote that ‘just as English rule created Irish nationalism, so too alien administration forged a county identity’. Mary Daly has traced the manner in which county loyalty first emerged in the Protestant settler community through the twice-yearly meetings of grand juries and the consequent growth of county towns; the significance of counties as parliamentary constituencies, which caused all the MPs from a particular county (including those representing boroughs) to work and vote together in the Irish parliament as an interest group; and the production of county histories in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Later, the county was appropriated as a mode of organisation by Irish nationalists and land reformers, including O’Connell, the Tenant Right League, the Land League and the Home Rule movement. The predominance of county constituencies after the Act of Union meant that the politicisation and mobilisation of the masses was usually done on a county basis, while the replacement of grand juries by democratically elected county councils in 1899 made them the primary unit of local government. Perhaps most significantly of all, the Gaelic Athletic Association developed a strong, popular, visceral county loyalty, akin to the parallel growth of political and cultural nationalism, which percolated down to all levels of society and saturated sporting, social and public life with an identity that transcended all others, including town, village and parish. This local ‘nationalism’ is typified by the invention of county flags utilising the local GAA colours, the evolution of ‘county anthems’ sung on match days and the growth of county associations in the Irish diaspora.In conclusion, Ireland has never been divided into 32 administrative counties. Excluding the Dublin liberties, Ireland had 40 counties from 1716 to 1838, 41 from 1838 to 1899, and 39 from 1899 to 1920. Since 1922, independent Ireland has had successively 31 (1922–86), 32 (1986–94) and 34 (since 1994) administrative counties. Northern Ireland has had eight (1920–73), and none since 1973. As a result, a modern unified Ireland under its current local government systems would be a 34-county and 26-district state! HI

Matthew Potter is Historian with the Mount St Lawrence Cemetery Joint Project, a collaboration between Limerick City Council and Mary Immaculate College.

Further reading

M.E. Daly (ed.), County and town: 100 years of local government in Ireland. Lectures on the occasion of the Local Government Act 1898 (Dublin, 2001).T.W. Moody, F.X. Martin & F.J. Byrne, A New History of Ireland, Vol. IX. Maps, genealogies, lists: a companion to Irish history, Part II (2) (Oxford, 2011).P.J. O’Connor, Seeing through counties: geography and identity in Ireland (Newcastle West, 2006).A.J. Otway-Ruthven, A history of medieval Ireland (London, 1968).