G.E.M. Anscombe—Irish-born philosopher

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2020), Volume 28An incisive thinker with a flamboyant personality, she was a leading figure in the ‘Golden Age of female philosophy’.

By John Hayes

Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe, the most considerable female philosopher of the twentieth century writing in English, was born in Limerick on 18 March 1919 and was baptised in St Mary’s Church of Ireland cathedral on 7 May 1919. Her parents were Gertrude Elizabeth (née Thomas) and Allen Wells Anscombe (b. 1885), a Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF) officer, with an address at Llangattock, Wales. According to UK National Archives, Capt. Anscombe was severely wounded by shell fragments at Puisieux, Pas-de-Calais, on 27 February 1917 and was treated in Guy’s Hospital, London, for neck injuries. After recuperation—during which time he received a ‘wound gratuity’ of £145 16s. 8d.—Anscombe was judged ‘fit for home service’. He was assigned to the 3rd Reserve Battalion of the RWF in Limerick on 29 July 1918 and rented a house, ‘Glanmire’, on the North Strand to accommodate his wife and two sons. (Matthew Potter, Limerick Museum, has recently identified ‘Glanmire’ as now No. 3, ‘The Trossachs’, Clancy’s Strand.)

Above: No. 3, ‘The Trossachs’, Clancy’s Strand, Limerick (centre, with open gate), birthplace of G.E.M. Anscombe on 18 March 1919, when it was known as ‘Glanmire’, North Strand. (Keith Wiseman)

‘Sedentary duties’ only

Although Anscombe’s sight was affected following the incident in France, his superiors decided on 2 January 1919 that ‘he could not be spared’. Nevertheless, on 6 March 1919 Anscombe was referred to the Cork Eye and Ear Hospital, where a permanent injury to his left eye was confirmed. This finding was considered first by a medical board in Limerick on 27 March and again on 30 April at the dispersal hospital, Portobello, Dublin, where he was pronounced fit for ‘sedentary duties’ only.

Meanwhile, on 9 April 1919 a deteriorating security situation led to the designation of Limerick as ‘a special military area’. This provoked a general strike and the establishment of the Limerick Soviet. The maintenance of public order presented the city’s constabulary and the resident military forces with formidable challenges. Perhaps for that reason the Anscombe family, including the newly arrived Elizabeth, left Limerick at the end of May 1919. Allen Anscombe spent all of 1920 as a chief instructor at the Rhine Army General and Commercial College in Cologne and was finally demobilised on 7 January 1921. A headmaster before the war, he became head of the engineering (i.e. science) department at Dulwich College and taught physics there until his death in 1939.

‘Golden Age of female philosophy’

After education in the nearby Sydenham High School, in 1937 Elizabeth went up to St Hugh’s College, Oxford, where she read Classics and Philosophy. During her first year she converted to Roman Catholicism; her parents strongly disapproved. She again displayed independence when in 1939 she contributed an essay entitled ‘The War and the Moral Law’ to a pamphlet in which she applied then widely disregarded ‘just war’ principles to the British declaration of hostilities on Germany. She considered the British government’s case untenable because of its reply to US President Roosevelt’s request ‘for assurances … that civilian populations would not be attacked’. The UK agreed to refrain from such attacks (which Anscombe deemed murderous) only if Germany did likewise.

Elizabeth Anscombe became a leading figure in what has since been considered the ‘Golden Age of female philosophy’, along with Philippa Foot (née Bosanquet), Mary Midgley (née Scrutton), Iris Murdoch and Mary Warnock (née Wilson), in male-scarce wartime Oxford. They opposed attempts (notably by A.J. Ayer) to reduce moral evaluation to an individual’s emotional response.

Literary executor of Ludwig Wittgenstein

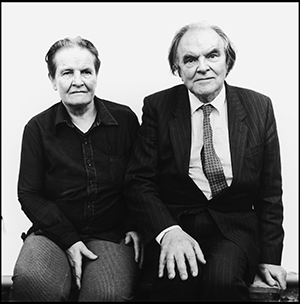

Above: G.E.M. Anscombe, with her husband and fellow philosopher Peter Geach, at Cambridge in 1990. (Steve Pyke/Getty Images)

In 1941 Elizabeth graduated from Oxford and married a philosopher and fellow Roman Catholic convert, Peter Geach (b. 1916), then a conscientious objector. She retained her patronymic and continued to be addressed as ‘Miss Anscombe’—even by her husband. In 1942 she commenced graduate studies at Newnham College, Cambridge. Meanwhile, she had become obsessed with ‘phenomenalism’, a sceptical theory confining knowledge to what appears to the senses. She wrote that ‘for years’ she ‘would spend time … staring at objects’, saying to herself: ‘I see a packet. But what do I really see? How can I say that I see here anything more than a yellow expanse?’

Liberation came through the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (b. 1889), who throughout the 1930s attracted a cadre of students at Trinity College, Cambridge. Wittgenstein was sceptical of the philosophical ability of women but admitted Anscombe to his post-war classes, addressing her as ‘old man’—she wore ‘slacks and a man’s jacket’. Wittgenstein thought phenomenalism amusing and yet provocative of important questions. Indeed, he himself was still pondering on how knowledge is possible until a few days before his death in 1951. Anscombe edited his notes on this issue in On certainty (Oxford, 1969). Wittgenstein had published just one book in his lifetime, called (for brevity) the Tractatus (1921). As one of his literary executors, Anscombe greatly augmented his bibliography by preparing several volumes of his manuscripts for posthumous publication.

Anscombe had been appointed a research fellow at Somerville College, Oxford, in 1946 and maintained an open house for grateful graduate students at 27 St John Street. In 1948 she visited Wittgenstein in Dublin. He was staying in Ross’s Hotel, Parkgate Street (since rebuilt as the Ashling Hotel), and working on philosophical psychology—what it is to be a human being with beliefs and desires. During Anscombe’s stay, the two had conversations on what became part two of his second major book, Philosophical investigations (1953)—edited and translated by her.

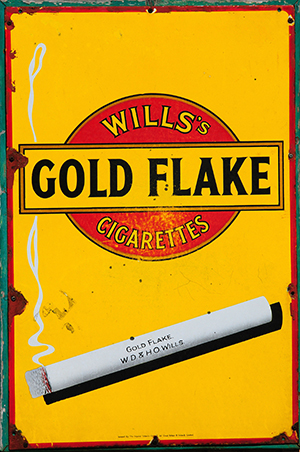

Above: The yellow packet at which Anscombe, a chain smoker, stared in her phenomenalist phase was probably of Gold Flake cigarettes, her preferred brand.

At the time of her Dublin visit she was suffering from insomnia and other symptoms following treatment by a hypnotist in England to cease smoking (a chain smoker, the yellow packet she stared at in her phenomenalist phase was probably of Gold Flake cigarettes). Wittgenstein was kind to her and introduced her to the Palm House in the Botanic Gardens and Bewley’s Café. He advised her to consult his former student and friend Maurice O’Connor (‘Con’) Drury, who, after war service in the Royal Army Medical Corps, had taken a post in psychiatry in St Patrick’s Hospital, James’s Street. Con Drury helped restore her sleep through his good sense and friendliness. Long-term, he advised—as did Wittgenstein—that she resume smoking. She left Dublin much refreshed.

In turn, Anscombe was central to her mentor’s support when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in late November 1949. She invited the ailing Wittgenstein to the family home and he stayed there—a visit to Norway excepted—from April 1950 to February 1951. As his disease advanced, he moved to the home of a former Royal Army Medical Corps colleague of Con Drury’s, Dr Edward Bevan, in Cambridge, to be close to Addenbrooke’s Hospital for treatment. Wittgenstein died on 29 April 1951 with Anscombe and Drury by his bedside.

Principled opposition to the killing of innocents

Consistent with her opposition in 1939 to the direct targeting of non-combatants in war conditions, in 1956 she proposed a motion at a ‘Convocation’—whose eligible voters included holders of an Oxford master’s degree—to reject a University plan to confer an honorary doctorate (LLD) on Harry S. Truman. Her argument was that, as US president, Truman had ordered the indiscriminate bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945 as a means of averting anticipated American military losses and that this was tantamount to murder. Only four voters agreed—among them Philippa Foot, granddaughter of an American president, Grover Cleveland.

In 1958 Anscombe published an article entitled ‘Modern moral philosophy’, challenging, in trenchant terms, philosophical trends that undermined the moral principle prohibiting the killing of innocents in all circumstances. She labelled these trends ‘consequentialism’, such that any action can be regarded as permissible if the anticipated consequences benefit a majority. Her principled opposition to the killing of innocents was maintained with regard to abortion. If abortion wasn’t murder—she recognised that others (though not she) had reservations about the moral status of the foetus—it was still ‘nearly’ as evil, and she described sexual intercourse as normatively ‘a reproductive type of act’, so backing Pope Paul VI’s prohibition of contraception in Humanae Vitae (1968).

Anscombe was appointed to the chair of Philosophy in Cambridge in 1971. An incisive thinker, her writings were considered ‘hard going’ even by professional philosophers. A flamboyant personality, she was observed driving about Cambridge in a superannuated cab replete with children (she had seven of her own), cigar in mouth and monocle on eye.

Bloody Sunday

In August 1972, an editorial in The Human World—a quarterly review edited in Swansea—criticised the British government for ‘its toleration of the rule of rebels’ in ‘panic’ following ‘the misfortune at Londonderry’ and eschewing a ‘military solution’. In a letter to the editor, Anscombe wrote that Northern Ireland was ‘unnatural’; its borders had been drawn artificially to create ‘a Protestant majority’ and, moreover, its regime was oppressive towards Catholics. She agreed that ‘if you clobber them hard enough you can suppress revolt and the oppression can go on’, but proposed instead a ‘county by county plebiscite’ on joining the Republic of Ireland. The likely result—a reduction in the Roman Catholic population—would mean that the remainder would not have ‘to be kept down at all costs’.

Anscombe is associated with the ‘Virtue Ethics’ movement in moral philosophy. Led by Philippa Foot, this revived Aristotle’s approach to moral enquiry, focusing on how human beings can achieve a comprehensive goal of ‘living well’—in practice, through self-discipline, courage and fair dealing, guided by ‘good sense’. Anscombe had cleared the ground for this revival by her critique in Modern moral philosophy of canonical moral theories—Kant’s approach was ‘useless’ and J.S. Mill’s ‘stupid’, while contemporaries were ‘shallow’ and ‘provincial’. She believed, however, that a better theory first required an analysis of psychological concepts used by moral philosophers. This was the project of her book Intention (Oxford, 1979). An eminent philosopher declared it ‘the most important’ investigation of practical [action-guiding] reasoning since Aristotle’. Her husband demurred but claimed no special status in interpreting his wife’s mind, as he had ‘privileged access’ to her body only.

G.E.M. Anscombe died on 5 January 2001 and was buried adjacent to Wittgenstein in the ‘Ascension burial ground’, Cambridge. Her husband, Peter Geach, who died on 21 December 2013, was interred with her.

Prof. John Hayes is retired Head of the Department of Philosophy at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick.

FURTHER READING

G.E.M. Anscombe, The collected philosophical papers (Oxford, 1981).