Frowning Ruins: The Tower Houses of Medieval Ireland

Published in Anglo-Norman Ireland, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Revival, Issue 1 (Spring 1996), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 4

Bourchiers’ Castle, Lough Gur, County Limerick,

an elegant fifteenth century Irish Gothic tower house.

A tower house is a fortified medieval residence of stone, usually four or more stories in height. Like most of the surviving monuments of our medieval past, the majority of Irish tower houses are in poor condition, with collapsed walls and ivy shrouded exteriors reflecting centuries of neglect. Yet these ruins, the remnants of a major medieval building industry, provide a valuable source of information on life in Ireland during the later Middle Ages. An increasing number are being restored through both private and state initiatives, while there has also been a marked upsurge in academic interest in recent years.

The buildings were regarded as castles by their occupants. This classification continues today and tower houses are regarded as a species within the castle genus. Their evident defensive strength should not, however, overshadow their residential nature, for tower houses were primarily the defended homes of a wealthy landowning class and were erected by both Anglo-Irish and Gaelic families during the period from circa 1400 to circa 1650.

The identification of the tower house as a distinct unit of study among the castellated architecture of Ireland is of relatively modern origin. In 1858 the English antiquarian John Henry Parker made a fortnight’s tour of southern Ireland. Among the numerous historic monuments he visited he recognised a distinct class of free standing, castellated towers with similar architectural features, the tower house. Parker’s appellation, however, does not seem to have been readily adopted by contemporary Irish antiquarians. Thomas J. Westropp, for example, preferred to use the term peel tower, a name derived from a broadly similar medieval building series found in Scotland and northern England. The term tower house only gained greater acceptance from the 1930s onwards, largely due to the work of Harold G. Leask.

John Mulvany’s painting of Kilmallock, County Limerick c.1800. (Courtesy of The National Gallery of Ireland)

Dating, origins and distribution

Ireland at the close of the Middle Ages was heavily populated with castles; according to an English document of 1515 there were no less than 500 piles or castles throughout the country. Even today the exact number of castles and tower houses is by no means certain, and there are numerous ‘lost’ castles. Westropp’s comprehensive survey of County Limerick was based on information retrieved from historical documents and it identified a corpus of 405 buildings. Today the location of only 176 can be identified with certainty. Leask came up with a figure of around 2,900 castles throughout Ireland, the majority of which were undoubtedly tower houses (Fig.1).

Tower houses came into existence by the early fifteenth century, when a 1429 statute allowed the counties of the Pale to grant £10 to landowners towards their construction. The tower house at Kilclief, County Down was erected in the early fifteenth century. Where did the concept originate? They may have been scaled-down copies of earlier Anglo-Norman keeps. They may have developed as the secular equivalent of the belfry towers raised at Irish abbeys and monasteries during the fifteenth century. The concept may have been imported from England, Scotland or the Continent. Married to any discussion on origins, however, is the need to identify the reasons why tower houses became prominent in late medieval society

In a history of County Limerick published in 1826-7, the antiquarian P.J. Fitzgerald recorded that ‘the frowning ruins of many [castles] still remain as the solitary monuments of a long and gloomy period of distraction and anarchy’. This paints a rather grim picture of life in late medieval Ireland. While it is true that events in the fourteenth century such as the Bruce invasions and the Black Death did lead to social dislocation and economic recession, the effects on society may not have been as severe as is often portrayed. Roger Stalley and Tom McNeill, for example, have argued that there was no complete hiatus in building activity during this period. After a recession in the mid to late fourteenth century the construction industry recovered, building in a style—Irish Gothic—whose elements arrived from England between 1300 and 1350. Great social and economic changes did occur in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. There was a change from arable to pastoral agriculture, while research in east Galway, Meath, and the barony of Knockgraffon in Tipperary has shown that there was a fragmentation in major lordships, accompanied by a proliferation of both minor lordships and tower houses.

The Desmond Survey of the 1580s identifies a similar situation in County Limerick. The Elizabethan document is the first overall view of the county after the medieval period and it depicts a landscape divided up among lesser lords and tenants who paid dues in rents and services to their overlord, the Earl of Desmond. Precisely when this proliferation of lesser lordships occurred cannot be readily identified, but its correlation with the advent of tower houses from the fifteenth century onwards must be significant. In County Limerick tower houses show a marked concentration in the county’s fertile central plain. The rich land would have provided excellent pasture for cattle, a key factor in generating wealth for landowners. The tower house also emphasised the landowner’s position in society. Secure behind its walls, the tower house and bawn provided a landowner with protection from troublesome neighbours and raiders at a time when forays were the principal form of Irish warfare.

Monea Castle, County Fermanagh, was built in the aftermath of the Ulster plantation of 1609 and displays Scots Baronial architectural features.

The architecture of tower houses

No two tower houses are ever identical. While the same assemblage of architectural features occurring in one tower house can be present in a neighbouring building (thereby suggesting that both were erected at a similar period), the location, variety and number of features present in each individual building can differ. The presence of a shared architectural assemblage does, however, allow the buildings to be defined as a distinct architectural series. In addition, each tower house functions as a self-contained unit with the chambers inside stacked vertically, one over the other. Both of these factors result in the conformity of appearance throughout Ireland.

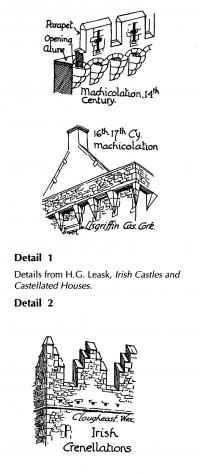

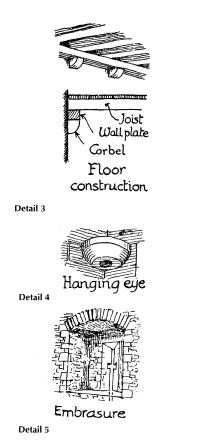

The majority of tower houses have a rectangular, nearly square, plan with tall walls which taper upwards from thick, base battered foundations (Fig. 2). The entrance is at ground floor level, framed by an arched doorway of dressed stone. The presence of a small hole set in one of the stone door jambs can betray where  an iron door, or yett, once hung. Looking upwards a stone box at parapet level may be set directly out over the doorway. The open floor of this machicolation (Detail 1) allowed missiles to be dropped on assailants below. Bartizans and tourelles can jut out from an upper corner or the crenellated parapet (Detail 2), both providing the circuit of the building with additional defence. The entrance may lead into a small lobby, in the roof of which is often positioned a murder hole, another defensive feature and one which enabled the occupants to dispatch any unwelcomed visitor from the safety of the building’s first floor level. On one side of the lobby there may be the entrance to a small subsidiary chamber (perhaps a porter’s station), while often on the other side is the doorway leading onto the spiral staircase which gives access to the upper floor levels. The lobby may lead through to the large main chamber. Both main and subsidiary chambers may lie under stone barrel vaults, but the stress which vaults placed on the side walls often restricted their number in the finished tower house. As a result, the builders more often used wooden floors, set on joists which spanned the room and were supported on beams placed on stone supports (corbels) projecting from both side walls of the chamber (Detail 3).

an iron door, or yett, once hung. Looking upwards a stone box at parapet level may be set directly out over the doorway. The open floor of this machicolation (Detail 1) allowed missiles to be dropped on assailants below. Bartizans and tourelles can jut out from an upper corner or the crenellated parapet (Detail 2), both providing the circuit of the building with additional defence. The entrance may lead into a small lobby, in the roof of which is often positioned a murder hole, another defensive feature and one which enabled the occupants to dispatch any unwelcomed visitor from the safety of the building’s first floor level. On one side of the lobby there may be the entrance to a small subsidiary chamber (perhaps a porter’s station), while often on the other side is the doorway leading onto the spiral staircase which gives access to the upper floor levels. The lobby may lead through to the large main chamber. Both main and subsidiary chambers may lie under stone barrel vaults, but the stress which vaults placed on the side walls often restricted their number in the finished tower house. As a result, the builders more often used wooden floors, set on joists which spanned the room and were supported on beams placed on stone supports (corbels) projecting from both side walls of the chamber (Detail 3).

Usually the floor plan is repeated in each of the upper levels, and each level’s internal space is divided between a main chamber and a subsidiary chamber. The timber doors throughout the building were hung on ‘hanging eyes’ (Detail 4) or pivot holes placed at the top inner side of the doorway, into which the door stile was inserted. The chambers can contain deep wall cupboards and fireplaces (though the latter are rarely found in subsidiary chambers). Long stone-roofed passages, housed in the thickness of a side wall, lead to the castle’s latrines. The latrine is set over a downward flue which allowed waste matter to fall through the shaft to an opening in the external wall-face where it was jettisoned from the building.

The narrow slit-like windows within their deep embrasures (Detail 5) at lower floor levels provided little light to the internal living area but had a necessary defensive quality. At upper floor levels defensive considerations were not as paramount; the upper levels in the building may have elaborate mullioned windows, with carved heads. Projecting mouldings (hood moulds) set over the window on the external wall face were designed to throw rain water away from the opening. Such windows could also be accompanied by  stone seats placed at either side of the window embrasure. The spiral staircase terminated at the parapet (sometimes in a caphouse) where there was a wallwalk, protected by stepped crenellation. The building lay under a pitched roof.

stone seats placed at either side of the window embrasure. The spiral staircase terminated at the parapet (sometimes in a caphouse) where there was a wallwalk, protected by stepped crenellation. The building lay under a pitched roof.

Variations in format do occur. Not all tower houses, for example, have rectangular floor plans. At Castle Troy, County Limerick, there is a unique and ingenious use of space within a five sided building, while there is also a small corpus of round tower houses, represented by buildings such as Ballynahow, County Tipperary. Side turrets can also be incorporated into the floor plan (particularly in north Leinster), as at Roodstown, County Louth. At buildings such as Castle Hewson, County Limerick, a straight flight of stone steps housed in the thickness of a side wall was favoured instead of a spiral staircase.

An early seventeenth century traveller, Fynes Moryson, stated that Irish cattle ‘eat only by day, and are brought at evening within the bawns of castles where they stand or lie all night in a dirty yard without so much as a lock of hay’. The bawn was a fortified enclosure where outbuildings (perhaps of timber) were located. The bawn walls were usually of stone and enclosed a rectangular area surrounding the tower house. Of a less substantial nature than the walls of the tower house, many bawns have been demolished. In County Limerick they have a particularly low survival rate, with only fourteen examples remaining.

Domestic life in a tower house

The most widely quoted description of life in a tower house is Luke Gernon’s 1620 account of a coshering, or feast, where the entertainments were held in the uppermost storey. Hospitality was showered upon the guests from the moment they entered until the time they departed. The fire was kindled in the chamber, the bard sang, and food, alcohol and tobacco were consumed in large quantities, though the guests may have been expected to share the castle’s beds since furniture was scarce. In a second document, written in 1644, the French traveller Bouillaye le Gouz states that the houses of the nobility were ‘nothing but square towers’, poorly lit, with little furniture and with floors covered in rushes a foot deep ‘of which they make their beds in summer, and straw in winter’. This account is perhaps a little too contemptuous. When compared to the thatched, mud-walled cabins in which the majority of the contemporary population dwelt, the tower house was a secure homestead with provision for heat and sanitation.

With defences designed to resist petty plunderers rather than marching armies, the tower house was not a citadel but the country seat of its time, bustling with the activities of everyday home life and the administration of the estate. The available evidence suggests that the buildings were not isolated on the landscape, but were economic and social centres in the rural community. A number of castles included in the pictorial maps of the Cromwellian Down Survey are accompanied by smaller buildings, while The Civil Survey of the 1650s records orchards, gardens, cottages, mills and dovecots associated with castles. Archaeological excavations in the vicinities of tower houses have produced evidence of contemporary activity in the form of cultivation furrows, out-houses, terraces and trackways. Pat O’Connor’s study of urban settlement in County Limerick identified at least thirty cases where a medieval church was located in close proximity to a tower house. This is further evidence for settlement nucleation, and echoes Luke Gernon’s statement that in every village there was a castle and church, with the villages ‘distant each from other about two miles’.

Like surviving stretches of town walls or medieval churches, the presence of a tower house can often indicate of the former medieval importance of a modern urban settlement, for a town’s merchants would have required protection in the event of a raid. Mulvany’s painting of circa 1800 shows a lively street scene in Kilmallock, County Limerick (Fig. 3). The street is framed by the roofless shells of merchant’s houses and stores in a trading centre which once had strong mercantile connections with Cork and Limerick. In 1690 John Stevens wrote: ‘The ruins show it to have been a good town, the houses being of stone, lofty and large, but most of them ruined, and but few of those that remain inhabited’. Pat O’Connor has highlighted lack of patronage, absentee landlords and economic eclipse by Charleville as reasons for the town’s post-medieval decay.

![This computer enhanced reconstruction of Oola castle, County Limerick, a later tower house, shows the building as it may once have looked, with whitewashed walls,gables crowned with chimneys and mullioned windows.[Donnelly, Alexander & Pringle]](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/87_small_1304691788.jpg)

This computer enhanced reconstruction of Oola castle, County Limerick, a later tower house, shows the building as it may once have looked, with whitewashed walls,gables crowned with chimneys and mullioned windows.[Donnelly, Alexander & Pringle]

The defences of the tower house and its bawn engaged at two levels. At the first level the bawn’s shot holes and loops worked in conjunction with similar features in the tower house to hold an enemy away from the defensive circuit. If this circuit was breached then a second category of defences came into play as the inhabitants retreated into the tower house, firmly shutting the yett and wooden doors behind them. Shot holes made the doorway a ‘killing zone’, while a box machicolation on the parapet allowed missiles to be dropped on the heads of the aggressors below. If the enemy managed to break into the building the defenders closed the doors on the entrance lobby and then retreated upstairs. As the intruders stood in the lobby they could be attacked through the murder hole above their heads.

This is the theoretical application of the tower house defences, but architectural study in County Limerick has established that not all of these defensive features were present. Not all were deemed necessary for security—perhaps the cost was too high. While the medieval annals often refer to the capture of castles, it is unfortunate that the exact mechanisms used are rarely related, though some tantalising information does occasionally present itself. It is only with the Tudor conquest of the sixteenth century that information on tactics used in sieges increases, usually in government reports. This also corresponds to a period which witnessed an increase in the size of armies and greater use of artillery. The defences of the tower house were not designed to cope with either and many buildings suffered heavily. Detailed accounts of the siege of Glin Castle, County Limerick, in 1600 depict a bitter fight for possession.

The rebellion of 1641 saw a return to more traditional methods of warfare. Lacking artillery, the Irish raided or besieged the settlers in their tower houses and castles and attempted to starve them out. The arrival of the New Model Army in 1649 heralded the end of an inconclusive war. Well equipped with artillery, Parliament’s army crushed all opposition, including that thrown up by the humble tower house. In a letter to the speaker of the House of Commons in February 1650 Cromwell briefly mentions his capture of the tower house of Kilbeheny on the Cork/Limerick border. In contrast to his usually detailed accounts of military operations, Cromwell’s lack of detail may suggest that the building fell with relative ease.

The later tower houses and the end of a building tradition

The later tower houses and the end of a building tradition

There is a series of buildings which belong to the last phase of the developmental sequence of tower houses, during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In Munster the buildings are characterised by their gabled walls, cruciform roofs, large mullioned and transomed windows, and gun defences (Fig. 4). As with earlier tower houses, elaboration and architectural detail differs from one building to the next, but certain features still betray their kinship with the earlier Irish Gothic building tradition; of more importance is the fact that they retain the function of self-contained units. The change in style reflects a general change in architecture during this period with the construction of major fortified houses such as Portumna, County Galway, and Burntcourt, County Tipperary. The desire for defence is still apparent in the form of shot holes and machicolations, but greater emphasis was now being placed on privacy, symmetry of plan, and increased provision of heat and light.

Erected by 1619, Monea Castle, County Fermanagh, (Fig. 5) is an example built in the aftermath of the Ulster plantation of 1609 and displaying Scots Baronial architectural features. The seventeenth century saw, however, a continuing shift towards low, thin walled fortified houses, as exemplified by Tully Castle, County Fermanagh, or Castle Baldwin, County Sligo, though defensive features such as murder holes and box machicolations could still be retained. Control of the country had now passed to the English government in Dublin, with consequent changes in social, political and economic organisation. One of the last examples of a traditional tower house is Derryhivenny Castle, County Galway, erected in 1643. A few tower houses were incorporated into the fabric of later country houses, as at Leap Castle, County Offaly, while other buildings were adapted for more prosaic use. At Ballyvoreen, County Limerick, there is an example of a tower house which was cut down in height to just above ground floor level, the remaining structure being converted for use as a two-storey farmhouse. In the aftermath of the Cromwellian settlement of the 1650’s some tower houses, such as Gortnetubbrid, County Limerick, were reused as garrisons for the New Model Army.

For the majority of the buildings, however, the seventeenth century brought about what Westropp described as a ‘dull dead ending’ for the building series, and they remain under siege today from neglect, stone-robbing and frost. The map (Fig. 6) displays the location of the 176 tower houses known on the Limerick landscape. Of this number, 102 definite or probable examples have been demolished. A further twenty-eight are severely damaged and only forty-six remain in a good state of preservation. As this erosion of our medieval past continues, clearly some form of long term strategy needs to be initiated to ensure that the best preserved examples from each county are protected for future generations.

Colm Donnelly has recently completed a PhD thesis on the tower-houses of County Limerick in the Department of Archaeology and Palaeoecology, Queen’s University. Belfast.

Further reading:

M. Craig, The Architecture of Ireland from earliest times to 1880 (London 1982).

H.G. Leask, Irish Castles and Castellated Houses [revised edition] (Dundalk 1951).

P.J. O’Connor, Exploring Limerick’s Past: An Historical Geography of Urban Development in County and City (Newcastle West 1987).

M. Salter, Castles and Stronghouses of Ireland (Malvern 1993).