Frank Hugh O’Donnell: a virulent anti-Semite

Published in Issue 1 (January/February 2020), Volume 28‘Crank Hugh’ left a trail of bitterness and recrimination.

By Colum Kenny

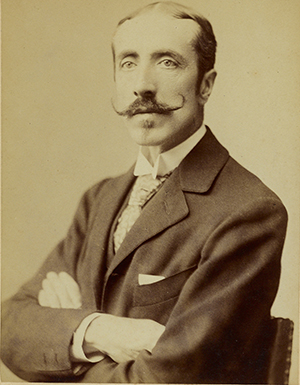

Above: Frank Hugh O’Donnell—‘an important figure in the history of British [sic] anti-Semitism’.

‘It is not merely a general ascription of qualities but a formal assertion of inherent and derogatory characteristics, displaying a deep-seated racial antipathy. As such, it represents a rather rare form of anti-Semitism, one hardly ever displayed in Edwardian England. It would be more familiar in the context of certain German writings of the 1930s. In this respect, O’Donnell is an important figure in the history of British anti-Semitism …’

‘Crank Hugh’

O’Donnell was once a promising member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, of which he wrote a vivid history, but his nickname ‘Crank Hugh’ reflected later perceptions of him. He took contradictory positions on current events and was unhelpful to Parnell. He was suspected of being in the pay of various European governments and of the Boers. He was a disruptive influence in nationalist politics, and even Yeats described him as ‘a political enemy’.

O’Donnell, a sometime journalist, wrote for two papers that concern us here in particular. One was Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman, the other the New Witness of Cecil Chesterton in London. Even earlier, notes Deirdre Toomey (DNB), in 1897 he wrote pseudonymously for United Ireland, supposedly from a revolutionary group called ‘Fuath na Gall’. The name means ‘hatred of foreigners’.

Besides appearing in New Witness, O’Donnell was one of an anti-Semitic league campaigning in England for ‘clean government’. This led one correspondent in a British socialist paper to ask whether O’Donnell’s ideas of clean government ‘include the hounding from the country of everyone who is guilty of the crime of being of Jewish blood or creed’, and to accuse him of being a fomenter of ‘cruel and bloodthirsty hatred between races’.

New Witness was edited by Cecil Chesterton, younger brother of the well-known writer G.K. Chesterton and a close associate of the writer Hilaire Belloc. Both of the latter expressed anti-Semitic views. Belloc in 1912 had published some of O’Donnell’s anti-Semitism in Eye-Witness, forerunner of New Witness. It included this gem:

‘In France and Italy, for example, every representative of the old European civilization, whose prominence is feared by the Jew, is the object of a universal and Argus-eyed inquisition … There are hundreds of thousands of representatives of European civilization in several modern countries who know that they are registered, marked down, tabooed, reduced to helplessness and poverty, solely through the vast organization controlled by the Jew.’

O’Donnell was soon writing regularly for New Witness. His contributions continued, despite Belloc ostensibly telling Cecil Chesterton that they went too far:

‘… the detestation of the Jewish cosmopolitan influence, especially through finance, is one thing, and one may be right or wrong in feeling that detestation or in the degree to which one admits it; but mere anti-Semitism and a mere attack on a Jew because he is a Jew is quite another matter …’

O’Donnell in New Witness referred back to an alleged Jewish conspiracy to foment the Boer War, a constant theme of his earlier columns in the United Irishman. Then the English were depicted as hand in glove with Jews; now they were victims of ‘the tribe’:

‘The tribe had recently induced those [British] Christians to spend £230,000 and tens of thousands of Christian lives in order to secure its African mines and investments. Canaan-on-Thames was, indeed, a Promised Land.’

Jews were to blame for corrupting others and, chillingly, society needed to be cleansed of them: ‘Sir Ikey Moses and Mr Pecksniff Chadband may infect English public life. They do not constitute it. A sanitary operation is required …’. The left-wing civil servant Archibald Robertson pointed out at the time that O’Donnell seemed to accept as true a recent accusation of ritual murder by Jews—the old blood libel then being given new life in the widely reported Russian Beilis case. Robertson deemed the articles in New Witness ‘the most atrocious, scurrilous and malevolent outpourings of anti-Semitism that have ever been offered to English readers’.

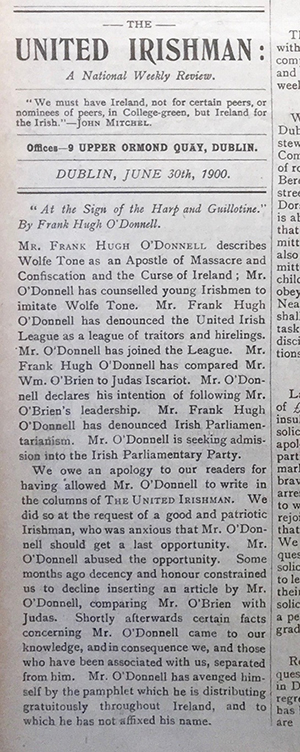

‘The Foreign Secretary’ in the United Irishman

‘The Foreign Secretary’ in the United Irishman

In 1899–1900 O’Donnell had written for Griffith’s United Irishman and brought to that paper also a scurrilous anti-Semitism. His principal pen-name there was ‘the Foreign Secretary’, reflecting his acknowledged experience in foreign affairs. Both ‘Red Hand’ and ‘Lllendo’ are also thought to have been pen-names of his. His arrival coincided with a doubling of the size of the United Irishman. Its editor wrote that ‘Foreign affairs we trust to have dealt with by gentlemen versed in continental politics’ (3 June 1899).

The United Irishman first appeared on 4 March 1899 but the ‘Foreign Secretary’ did not appear in it until 1 July 1899, and during those first four months there was no anti-Semitic content. Coverage of the Dreyfus scandal was not merely even-handed but at times implied that he was innocent. Even the mere fact that Dreyfus was a Jew was mentioned just once (15 April 1899).

That tone changed suddenly as the Boer War erupted and dominated the news. From July onwards, especially during 1899, the ‘Foreign Secretary’ column was full of poisonous references to Jews, and there were anti-Semitic references elsewhere in the paper too. The ‘Foreign Secretary’ appeared for the last time on 31 March 1900. Thereafter anti-Semitism in the United Irishman declined significantly, although it was not entirely absent—most notably in 1904, when Griffith fuelled a controversy about Jews in Limerick. Laffan has said that Griffith later ‘outgrew’ such prejudice (DIB).

Criticism of the Boer War as an Anglo-Jewish conspiracy was common among both Irish nationalists and quite a few British socialists, as well as among French Catholics and politicians such as the anti-Semitic Lucien Millevoye, with whom Maud Gonne had two children. Gonne, working closely with Griffith at the time, wrote that the editor of the United Irishman was offered money to back the Boers but refused. He needed no enticement, however, to support such a battle against the British. In any event, or so she later wrote, she had financed him to some extent (from what ultimate source is unclear).

Above: Lucien Millevoye—criticism of the Boer War as an Anglo-Jewish conspiracy was common among Irish nationalists and quite a few British socialists, as well as among French Catholics and politicians such as the anti-semitic Millevoye, with whom Maud Gonne had two children.

Some writers have failed to distinguish between what Griffith actually wrote and what others penned for the paper that he edited (and for which he therefore shared responsibility but for which James Joyce, for one, partly excused him). He has been quoted, for example, as having ‘written’ one of ‘the Foreign Secretary’s’ most obnoxious articles:

‘I have in former years often declared that the Three Evil Influences of the century were the Pirate, the Freemason and the Jew … The swarming Jews of Johannesburg, who have gained the mining town the nickname of Judasburg, are the staunchest, though not the most valiant, snarlers in Chamberlain’s currish pack.’

(United Irishman, 23 September 1900)

O’Donnell here also quoted Thackeray’s pungent portrait of poor Jews, in the verses White Squall, on how ‘All the fleas in Jewry / Jumped up and bit like fury’.

‘A toothless cur baying at the moon’

Ironically, Griffith and O’Donnell fell out after the editor decided that ‘decency and honour’ constrained him to reject an article in which O’Donnell had compared the conciliatory nationalist leader and newspaper owner William O’Brien to Judas, who betrayed Jesus. O’Brien’s wife, as it happened, was the daughter of a Russian Jewish banker to the Czar. It seems, however, to have been ‘certain facts concerning Mr O’Donnell’ that caused the final break, facts that Griffith did not explain in his United Irishman editorial of 30 June 1900 but that may have been related to O’Donnell’s murky role in respect of foiling a proposal to bomb a British transport to South Africa. Maud Gonne was urging this on a Boer agent in Europe.

In retaliation, O’Donnell published pamphlets (At the Sign of the Harp and Guillotine and Wolfe Tone the informer) attacking Wolfe Tone as anti-Catholic and his 1798 French allies as despots indifferent to Irish people and their rights. Griffith retorted in an editorial (30 June 1900), stating that he had allowed O’Donnell to write for the paper ‘at the request of a good and patriotic Irishman who was anxious that Mr O’Donnell should get a last opportunity. Mr O’Donnell abused the opportunity.’ That Irishman was almost certainly Mark Ryan, a senior organiser in the IRB, which O’Donnell, Gonne and Griffith had all joined. Griffith may have found it hard to refuse Ryan a favour, because Ryan strongly supported the paper and both Ryan and O’Donnell lived in London and mingled there in Irish circles. Ryan had initiated the latter into the IRB but wrote later that O’Donnell had ‘no political convictions’. Soon the United Irishman (23 and 30 June and 10 November 1900) was attacking O’Donnell as a ‘black-guard, clever and foul-mouthed’, and as ‘a toothless cur baying at the moon’.

Griffith himself at that stage of his career was not averse to taking an occasional sideswipe at Jews in the stereotypically prejudiced fashion of the times, but O’Donnell had briefly brought to the United Irishman a level of persistent and vitriolic anti-Semitism that notably dissipated upon his departure. O’Donnell once blazed brilliantly across the Irish parliamentary landscape but burnt out, leaving a trail of bitterness and recrimination. Yeats called him a ‘mad rogue’ but perhaps the sharpest description of his character is by Patrick Maume in The long gestation, where (p. 38) he describes O’Donnell as someone ‘who devoured his life in anachronistic visions of neo-aristocratic nationalism and pouring out diatribes against scapegoats for the failure of his dreams’.

Colum Kenny’s The enigma of Arthur Griffith: ‘Father of Us All’ will be published later this year by Merrion Press.

FURTHER READING

C. Kenny, ‘Sinn Féin, socialists and “McSheenys”: representations of Jews in early twentieth-century Ireland’, Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 16 (2) (2017).

K. Lunn, ‘The Marconi scandal and related aspects of British anti-Semitism, 1911–1914’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of Sheffield (1978).