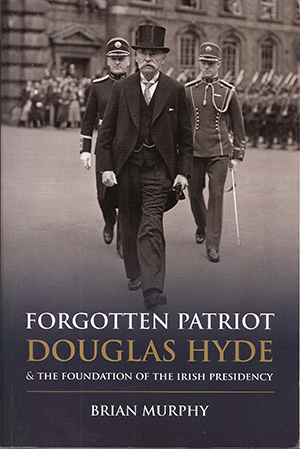

Forgotten patriot: Douglas Hyde and the foundation of the Irish presidency

Published in Book Reviews, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Reviews, Volume 25BRIAN MURPHY

Collins Press

€15.99

ISBN 9781848892903

Reviewed by: Tom Garvin

Tom Garvin is emeritus Professor of Politics at University College Dublin.

Brian Murphy has produced a well-researched and thoroughgoing biography of Douglas Hyde, first president of Ireland under the 1937 Constitution. Hyde was born in Castlerea, Co. Roscommon, in 1860, son of a Protestant rector in an area where a handful of Protestants lived surrounded by a sea of Catholic peasants which was gradually being turned into a community of owner-occupier farmers. He grew up to be a rather good organiser of a political movement, later to be termed the Gaelic League. In alliance with Eoin MacNeill he became a firm advocate of the Irish language and of the preservation and revival of as much of traditional Ireland’s habits, customs, games and poetry as was feasible. In many ways Hyde had an uphill struggle. In later life he reminisced about speaking to a young boy in County Sligo and being answered in English. When Hyde asked him in Irish why he wasn’t speaking Irish to him, the lad replied in English of a very Irish kind: ‘Sure amn’t I speaking to you in Irish?’

Brian Murphy has produced a well-researched and thoroughgoing biography of Douglas Hyde, first president of Ireland under the 1937 Constitution. Hyde was born in Castlerea, Co. Roscommon, in 1860, son of a Protestant rector in an area where a handful of Protestants lived surrounded by a sea of Catholic peasants which was gradually being turned into a community of owner-occupier farmers. He grew up to be a rather good organiser of a political movement, later to be termed the Gaelic League. In alliance with Eoin MacNeill he became a firm advocate of the Irish language and of the preservation and revival of as much of traditional Ireland’s habits, customs, games and poetry as was feasible. In many ways Hyde had an uphill struggle. In later life he reminisced about speaking to a young boy in County Sligo and being answered in English. When Hyde asked him in Irish why he wasn’t speaking Irish to him, the lad replied in English of a very Irish kind: ‘Sure amn’t I speaking to you in Irish?’

Probably rightly, Murphy concentrates on the later phases of Hyde’s life, when he had become a veteran of Irish nationalist politics and had retired from active campaigning. He had become disillusioned with the revivalist campaign, particularly when the movement that he and MacNeill had invented was hijacked by the physical-force wing of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) between 1911 and 1915. This was, of course, part of the political process that led to the Rising of 1916 and Irish partitioned independence in 1920–2.

Many years later, de Valera, looking for a candidate for the new office of president, saw the now aged veteran of long-ago battles as an ideal compromise. He was a highly respected representative of the old revival movement during the short era when it was not embittered by strife between physical-force and constitutionalist opinions, and he was a Protestant during a time when political Catholicism was ensconcing itself in power and claiming itself to be the Irish nation to the exclusion of all other faiths. In a way, de Valera’s choice resembled his insertion into the Constitution of a guarantee of the rights of the Jewish faith during a time of a murderous anti-Semitism in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. The one weakness in his choice was Hyde’s health; two years into his term of office he had a stroke. Had it not been for the world war, Hyde would certainly have had to resign his office. As it was, he soldiered on until 1945, but was partially bedridden for much of his term. David Gray, the representative of the United States, despite his public reputation for hostility to de Valera’s neutralism and his various ideological devices, seems to have been quite friendly with Hyde and reported: ‘President Hyde convalesced to such a degree that he could receive visitors in bed and dispense sweet Manhattan cocktails to Americans. He liked them himself.’

Hyde’s presidency was in large part a matter of legitimation of the state. For example, as Murphy recounts, the presidency had to avoid any notion that it was a successor of the old governor-general of the Irish Free State, and in no way was the president a representative in Ireland of the British crown, as was sometimes argued by hostile observers. In 1939 Hyde held a garden party in the grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin in which old Treatyites and Republicans mingled politely. Conspicuous by their absence were the militant republicans of Sinn Féin and W.T. Cosgrave, refusing to attend for equal and opposite reasons. Earlier, in 1938, Hyde attended an international soccer match (Ireland vs Poland), in technical violation of the GAA’s ban on ‘foreign’ games such as soccer. As president, Hyde had no choice but to refuse to ally himself with such a ban.

A theme that runs through the book is the importance behind the scenes of Michael McDunphy, a veteran civil servant who had considerable experience of the travails of the governors-general and a strong if often pedantic awareness of the sensitivities of someone who was, if not exactly the head of state, the nearest equivalent in a nation-state that was still finding its feet in a world of uncertainties and considerable upheaval. Hyde and McDunphy became good friends during the war years.

Another thread is Murphy’s account of the damaging effect that Irish neutrality had on relations not only with the United Kingdom but also with the United States. The book contains a fascinating account of Irish reactions to Hitler’s death by suicide in 1945. Eduard Hempel, the German representative in Ireland, was no Nazi and was an old-style career diplomat, interested in literature and quite familiar with Irish constitutional realities and political dilemmas, unlike his masters in Berlin. Hitler’s suicide resulted in de Valera’s visiting Hempel and signing a book of condolences, as was normal on the death of a head of state. The fact that Hitler was a genocide and a tyrant seems to have escaped the minds of Irish leaders. Nevertheless, it is clear from Murphy’s account that they were certainly well aware of the hostile reaction that the visit produced in neighbouring states at the time and for years after. The US State Department wrote to President Truman: ‘… general policy that Ireland missed the boat during the war and we should do the minimum towards her’.

This is an important contribution to the literature on Irish constitutional development in the twentieth century. De Valera’s originality with regard to institutional arrangements and his alliance with Hyde did indeed strengthen emergent Irish democracy in dark times.