‘Forced from this world’: massacre on the Mary Russell

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2009), Volume 17![Sailing Brigs [two-masted vessels similar to the Mary Russell] off the Cork Harbour 1851 by George Mounsey Wheatley Atkinson. (Private collection, Cork)](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/73_small_1252843084.jpg)

Sailing Brigs [two-masted vessels similar to the Mary Russell] off the Cork Harbour 1851 by George Mounsey Wheatley Atkinson. (Private collection, Cork)

Inquest

Next day an inquest was held, according to the practice of the time, in the presence of the dead. Coroner Henry Hardy presided, with Dr Thomas Sharpe. A ‘gentleman reporter’ from The Constitution or Cork Advertiser (all indented quotations below) described what he saw in the Mary Russell’s cabin:

‘There were seven human beings with their sculls [sic] so battered, that scarcely a vestige of them was left for recognition, with a frightful mess of coagulated blood—all strewed about the cabin, and nearly a hundredweight of cords binding down their bodies to strong iron bolts, which had been driven into the floor for that murderous purpose. Some of the bodies were bound round about six places, and with several coils of rope round their necks, and all were in a state of decomposition, so that it required a constitution of no ordinary strength to bear up against the spectacle, and the effluvia that arose from a confined cabin.’

The skull injuries had been inflicted with a crowbar, sufficient to cause almost instantaneous death. The coroner and jury were required to find how Captain James Gould Raynes, Francis Sullivan, John Keating, James Murley, Timothy Connell, John Cramer and William Swanson met their deaths.

Robert Callendar from New Brunswick, captain of the Mary Stubbs, an American ship plying between Belfast and Barbados, testified that on 23 June he saw the Mary Russell 300 miles from the Cove of Cork, flying distress signals. Hailed repeatedly, Captain Stewart eventually appeared. He said he had put down mutiny aboard his vessel, killing seven in the process, and asked Callendar, ‘for God’s sake come to my assistance’. When Callendar came, Stewart handed him a loaded pistol, gave a confused account of attempted mutiny, then showed the cabin and its contents, saying: ‘Am I not a valiant little fellow to kill so many men?’

Hearing Callendar’s voice, first mate William Smith and crewmember John Howes, both seriously wounded, emerged from the hold and begged his help. Callendar took them to his own vessel, leaving Captain Stewart three of the Mary Stubbs’ crew to sail his ship to port. The following day, when Callendar revisited the Mary Russell, Stewart, believing the loaned crew to be enemies, jumped overboard and was rescued twice before Callender had him removed to the Mary Stubbs. There, recognising Smith and Howes, he jumped overboard yet again (as described in the opening line).

Tragic story

Smith and Howes, cabin boy Daniel Scully and eleven-year-old passenger Thomas Hammond testified to the inquest. Their combined accounts made a tragic story. Captain William Stewart, an Englishman, described as a ‘kind, good master’, captained the brig Mary Russell, which in early 1828 took a cargo of mules to the West Indies. She left Barbados to return to Cork on 9 May with hides and sugar, carrying a crew of six.

Smith and Howes, cabin boy Daniel Scully and eleven-year-old passenger Thomas Hammond testified to the inquest. Their combined accounts made a tragic story. Captain William Stewart, an Englishman, described as a ‘kind, good master’, captained the brig Mary Russell, which in early 1828 took a cargo of mules to the West Indies. She left Barbados to return to Cork on 9 May with hides and sugar, carrying a crew of six.

At first all went well, but after a week at sea it was obvious that the captain was not himself. He looked ill and could not sleep, then told several people that God had warned him in a dream that his crew would kill him and seize the ship. First mate Smith argued with him—unsuccessfully—about the unreliability of dream messages. Captain Stewart gradually became suspicious of everyone, especially James Raynes, whom he disliked. Raynes socialised with the crew, speaking with them in Irish, a language Stewart did not understand. He thought that Raynes was conspiring against him. Raynes and the others emphatically denied this, but were disbelieved and threatened with injury if they spoke Irish again. The captain threw instruments and charts overboard, saying that Raynes had driven him to do this. He destroyed the log so that no written records could be kept. Finally, Captain Stewart boarded a passing ship to buy meat, and returned with a pair of pistols.

Stewart’s suspicions intensified. By 21 June he thought that Smith was plotting to kill him and, ignoring the mate’s denials, insisted on tying Smith’s hands behind his back. The others protested, but Smith gave way to humour Stewart. Smith, bound hand and foot, was placed in the lazarette (a shallow cellar under the main cabin floor). Captain Stewart, who at intervals recovered his former humanity, ordered the ship’s carpenter to make an air hole. Through this, Smith overheard what followed.

Each man summoned separately

![‘Representation of the interior of the cabin of the Mary Russell, with the bodies [numbered] as they lay on arriving in Cork on Thursday morning the 26th June, and four days after the tragical occurrence.’ (The Constitution or Cork Advertiser)](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/73_small_1252843144.jpg)

‘Representation of the interior of the cabin of the Mary Russell, with the bodies [numbered] as they lay on arriving in Cork on Thursday morning the 26th June, and four days after the tragical occurrence.’ (The Constitution or Cork Advertiser)

‘When Howes got away, the captain applauded Rickards for what he did, and said he would get 100 guineas from Lloyds, and that he, the captain, would get some thousands of pounds. What the boys did was from terror, as they were afraid of being murdered. Deaves began to cry and begged of the captain not to kill Howes, on which the captain scolded them and said: “Why should they spare him—was it to be murdered?”’

Stewart made Scully sign a statement that the crew planned to mutiny.

The captives remained on deck overnight, complaining about cold and discomfort, but gradually realised that Stewart had no intention of releasing them. With the boys’ help he dragged his prisoners down into the cabin, placed some on mattresses and Raynes in a berth, and eased their bonds. Next, he offered his crew the ship’s longboat. They accepted, but Stewart would not release the men to launch it.

Stewart decided that bonds alone were insufficient. Fixing metal bolts into the cabin floor, he devised for each man a rope noose, attached to the nearest bolt. Any free movement of the head would result in self-strangulation. His crew immobilised, Stewart intended to sail the ship home with the help of the boys, and as he possessed another set of instruments and charts this was feasible.

Unknown ship twice approached

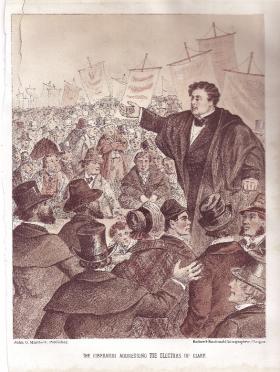

‘The Liberator addressing the electors of Clare.’ The Mary Russell massacre pushed the Clare election of 1828 off the front pages of Cork’s newspapers. O’Connell was engaged for the prosecution, but did not attend for the one day the trial lasted. (Maclure & Macdonald Lithographers, Glasgow)

By now the Mary Russell was flying a reversed ensign at half-mast, the recognised international distress signal. Next day, 22 June, an unknown ship twice approached the Mary Russell as though to intercept her, then suddenly sheered off and disappeared. According to Scully, Captain Stewart fell into deep despair, crying:

‘“The curse of God is on you all, there’s the ship come to us twice and went away”, and he took the crowbar that lay on the floor and struck the second mate Swanson right on the point of the skull and knocked him senseless at once! They all cried out most piteously “The Lord have mercy on their souls” and they all gave Scully their blessing, but Swanson, who was senseless, and Captain Raynes, who was saying his prayers, he then killed . . . while killing them, he called out: “You ruffians, you ruffians, you were going to take my life, but I’ll take yours . . .”. He then desired the witness to bring the beef and some grog, having cut some slices off, he drank, and smoked his pipe over the dead bodies. He then had Deaves called down, and he (the captain) raised his hand and said: “Look, boys, at my hand, how steady it is—I think no more of killing them than if they were dogs”.’

Then Captain Stewart tried to harpoon Smith through the air hole with a harpoon, injuring his left eye, shoulder, ear and face. The harpoon struck a bundle of hides, which felt like a human body, and Stewart, convinced that he had succeeded in killing Smith, gave up. Smith managed to untie his bonds and crawl from the lazarette into the hold.

Captain Stewart did not physically harm the boys but alternately threatened to shoot them or reassured them that the ship’s owners would reward them generously. Terrified and exhausted, they slept for several hours. When they awoke next morning, 23 June, a stopped watch hanging in Captain Stewart’s cabin had begun to go again, which he took as a sign that God wanted him to take back the weapons recently issued to the boys. Once the weapons were back in his possession, Stewart began to tie the boys up. ‘Little Tommy Hammond called out to the captain not to kill the boys, or he would die.’ Captain Stewart knelt down, handed his knife and pistol to Hammond, and swore on the Bible that he would not kill the boys—if he did, Hammond could shoot him. Yet he continued tying them up. Suddenly, Captain Callendar’s voice was heard outside. While Stewart spoke with him, Hammond untied the others, and they transferred to the Mary Stubbs. The inquest was adjourned to the Bridewell, Cork, for next day.

Stewart arrested and put on trial

Gravestone of Timothy Connell at Cill Muire cemetery, Passage West. (Helena Kelleher Kahn)

Next morning, police in Skibbereen notified the coroner that they had William Stewart in custody and that he had confessed to killing seven men. They added: ‘The above unfortunate man is well known here and was always considered extremely humane; he is very respectably connected, being nephew to Dr Stewart DLL of Clonakilty’. The coroner’s jury delivered its verdict: ‘That the several sailors and passengers were killed by the hands of Captain William Stewart being then and for some days before in a state of mental derangement’.

The trial of William Stewart for the murder of James Gould Raynes took place at Cork assizes on 11 August 1828 before Judge Baron Pennefather. The defence entered a plea of ‘Not guilty’ on the grounds that the prisoner was insane and incapable of knowing right from wrong. The prosecution, engaged by relatives of James Raynes, dwelt on the need to attach responsibility for a terrible crime. Both sides examined the witnesses, and no attempt was made to prove mutiny on the part of the crew.

Daniel O’Connell was engaged for the prosecution, but did not attend for the one day the trial lasted. Evidence emerged of previous strange behaviour on the part of Stewart. Dr Edward Townsend, local inspector of the county gaol, said Stewart suffered from monomania, defined as a condition in which ‘a man may be mad on one particular subject, and quite rational and sane on all others. This is the case until the cord on which insanity turns is touched.’

The judge was impressed by Dr Thomas Carey Osborne of the Cork Asylum, who said that, if the evidence was true, he had no doubt that the prisoner was insane. The jury gave its verdict as directed by the judge:

‘“Not guilty, having committed the act while labouring under mental derangement.” Immediately on the verdict being read, Captain Stewart threw himself on his knees, raising his hands to heaven as if in prayer, and continued in this posture for about half a minute.’

William Stewart was committed to the Asylum for Criminal Lunatics, Dundrum (now the Central Mental Hospital), but Dr Osborne arranged transfer to the Cork Asylum(on the site of the present South Infirmary). Stewart liked Osborne, and made him a unique present—a full-rigged model ship constructed to scale from bones. He had first to make tools to carve it, as he was not allowed knives.

After Dr Osborne died, Stewart had another psychotic episode and killed a hospital attendant. He was sent back to Dundrum, where he died in 1873. Apart from a subscription list set up to help widows and children, his helpless victims and their families attracted little attention. Patrick Connell made sure that his brother’s death at least would be recorded, on a gravestone in Cill Muire cemetery at Passage West:

‘You, gentle reader that pass this way,

Attend awhile, adhere to what I say,

By murder vile I was bereft of life

And parted from two lovely babes and wife,

By Captain Stewart I met an early doom

On board the Mary Russell the 22nd June

Forced from this world, to meet my God on high

With whom I hope to reign eternally.’ HI

Helena Kelleher Kahn is a returned emigrant who graduated from social work to social history.

Further reading:

Mr and Mrs S. C. Hall, Ireland: its scenery, character, etc. (London, 1840).

J. G. Lockhart, ‘The story of the Mary Russell’, in Fifty strangest stories ever told(London, 1930).

M. Reuber, ‘Public lunatic asylums 1800–1845’, in E. Malcolm and G. Jones (eds), Medicine, disease and the state in Ireland, 1650–1940 (Cork, 1999).

The Constitution or Cork Advertiser, June, July and August 1828.