Pilgrimages to Tone’s grave at Bodenstown, 1873–1922: time, place, popularity

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Featured-Archive-Post, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2015), Volume 23

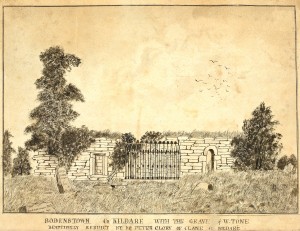

The grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown, ‘beautifully rebuilt by Mr Peter Clory of Clane, Co. Kildare’, in 1873. The railing was added in 1874. A shared awareness of the romance and symbolism of Tone’s tomb beside the ivy-covered ruined church could serve to maintain the ‘national spirit’. (NLI)

Regular, organised, mass pilgrimages to the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown, Co. Kildare, began in 1873. There was a gap in the 1880s and, after resumption in 1891, absences only from 1906 to 1910 and in 1921. They soon followed a pattern that has changed very little over the years. ‘Pilgrims’—the word ‘pilgrimage’ was first used in press reports in 1874 and ‘pilgrims’ in 1899—would arrive at Sallins from Dublin by train or by road and be joined by locals from the surrounding countryside; in later years they numbered tens of hundreds, even thousands. All would proceed or process from Sallins railway station to the graveyard, about 2.5km distant; bands would play along the leafy route to Bodenstown; wreaths would be laid solemnly on the grave; and an ‘oration’ would be delivered by an invited speaker, who would refer to current political matters as well as to Tone’s career and ideas. From 1891 all this would happen on a Sunday afternoon close to 20 June, Tone’s birthday. From 1911, when the pilgrimages were revived by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the political purpose was more evident. In 1914 and 1915 the procession from Sallins was a parade of units of the Irish National Volunteers; after 1922 there were rival official and unofficial pilgrimages.

Socio-economic status of the pilgrims

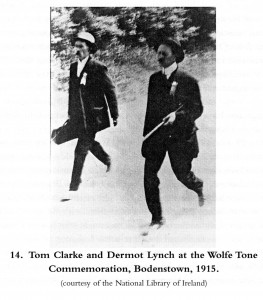

Seán O’Casey’s comment, made in 1938 and referring to 1913 (when he was secretary of the Wolfe Tone Memorial Committee), that the IRB ‘appealed only to clerks and artisans’ could equally have been applied to the Bodenstown pilgrimages throughout most of the period under discussion. From the 1870s there was IRB influence. From 1891 they were organised by bodies associated with the IRB: first the National Club Literary Society, later the Young Ireland League and after 1898 the Wolfe Tone Memorial Committee. The orators at the pilgrimages of 1876 and 1880 were IRB men, James O’Connor and John Daly respectively. In 1897 the orator of the day was Charles Doran, in 1901 it was P.N. Fitzgerald, in 1902 P.T. Daly and in 1905 John MacBride, all of them IRB men. The resumption of pilgrimages in 1911 (after a five-year break) was the doing of Thomas Clarke, who addressed the pilgrims at Bodenstown in 1912 and in the three following years.

It is interesting to consider the ‘day jobs’ of these orators: O’Connor was a journalist, John Daly had been a carpenter, Doran was a civil engineer, Fitzgerald a commercial traveller, P.T. Daly a printer, MacBride had no trade and Clarke was a tobacconist.

It is also interesting to compare the train fare from Dublin with the earnings of men in the economic classes indicated by O’Casey. The return fare in 1893 and 1901 was 1s.; in 1911 it was 1s. 6d. Some idea of ability to pay can be obtained from the ‘Appointments vacant’ columns in the Freeman’s Journal. On 6 January 1890 one read: ‘Traveller, wanted in connection with a flour mill in the south of Ireland, a competent traveller who knows the business well and has some knowledge of book-keeping . . . 18s. weekly’. A year later to the day there was a vacancy for an experienced provisions and grocery assistant who ‘must know his trade thoroughly’ to be paid £30 per year, which works out at 11s. 6d. per week and probably included accommodation. These were exactly the kind of positions held by IRB men, as they gave a degree of independence and the possibility of making contact with other IRB men whilst travelling around the country or whilst en-gaging with suppliers and customers. The train fare to Sallins for what may have been a man’s only excursion in the year must have been manageable to men of the skilled working class or lower middle class.

Buying a bicycle to travel by road meant saving up for some time or obtaining credit. In the Kildare Observer (25 March 1905) M. & J. Dawson, of Maynooth, advertised cycles (‘new machines, fully guaranteed’) from £5 10s. (‘cash and easy payments’). One can safely suppose that many of the bicycles that went to Bodenstown had been purchased second-hand at lower prices.

Social bonding

Thomas Clarke (left) and Dermot Lynch (right) at Bodenstown in 1915. Clarke gave the oration in that and in the three previous years. (NLI).

The companionship of travelling from Dublin or other places in a group for a common political or (at least) recreational or sentimental purpose could prove to be lifelong and could be a reason for becoming a regular pilgrim. Exchange of political ideas in conversation on the special train or the brake from Dublin, and during the 30-minute walk from Sallins to Bodenstown, or shared awareness of the romance and symbolism of Tone’s tomb beside the ivy-covered ruined church in Bodenstown churchyard could serve to maintain what nationalists called ‘national spirit’ and raise ‘hopes of national independence’. They could even turn pilgrims into fervent political activists. At the very least, experiences such as the sharing of food and drink with strangers, or sheltering in close company from a shower of rain, could produce lasting friendships.

The recreational aspect of the Sunday excursion into the countryside was important. Its potential for enhancing nationalist sentiment had been strongly argued in a letter published in the Nation on 3 August 1872. This letter may have inspired the members of the Dublin Wolfe Tone Band to commission a new stone for Tone’s grave and to organise a public ceremony for its laying in 1873. Thereby they started the custom of annual pilgrimages to Bodenstown. Even before 1872 there were recreational visits. One police report in the Fenian papers (National Archives, 4763/R) was of a picnic near Tone’s grave in 1869. There is a gem of an instance of a picnic in the archive of the Bureau of Military History where Thomas Pugh, a member of the Irish Citizen Army, records sitting on the grass eating lunch with James Connolly at the pilgrimage of June 1915. It is not difficult to believe that picnicking was the norm for most pilgrims. For others there was the possibility of refreshment in Sallins, the place of departure and return on foot. At that time it was an industrial village that had developed with the coming of the Grand Canal. Most likely it had many public houses. After the pilgrimage in 1900, the Kildare Observer reported that, once the orator’s speech was over, the crowds proceeded back to Sallins,

‘… where the excursionists from Dublin made fun for themselves. A good deal of drinking, shouting, cheering and jostling prevailed, and coming towards 7 o’clock matters took a serious turn by two parties falling into the canal, but they were promptly rescued. A large part of the crowd had come into Naas, and as they left Naas Station for Dublin by the 8.25 p.m. train, they, needless to say, created no little amount of noise and confusion.’

The opposite sex

Another reason for the popularity of Bodenstown was no doubt the presence of the opposite sex. In its coverage of the ceremony in March 1874 to mark the erection of a railing around Tone’s grave the Nation mentioned the presence of ‘a considerable number’ of women; in June 1893 the Leinster Leader reported that the two special trains arriving from Dublin ‘were closely packed’ with both men and women; and in 1899, when attendance well exceeded 1,000, ‘a conspicuous feature was the proportion of the feminine element comprised in the crowds thronging towards Bodenstown’. Evidently Tone’s grave, perhaps because it was a lieu de mémoire, a site redolent of patriotic sacrifice, was a place where women and girls could go and be in male company respectably. From 1911 pilgrims were more militant. In 1913 a contingent of women, the Daughters of Ireland (known also as Inghinidhe na hÉireann), marched from Sallins to Bodenstown and placed a wreath on Tone’s grave. This they did directly behind a contingent of so-called ‘National Boy Scouts’. They were all young people. Both the ‘Scouts’ (better known later as Fianna Éireann) and the women (soon to regroup as Cumann na mBan) were to be present at successive Bodenstown pilgrimages until and after 1922. Throughout the period of unrest that began in 1913 women were prominent. In June 1916, when the political situation was tense a few weeks after the suppression of the Easter rebellion, the Kildare Observer reported that the small crowd at Bodenstown was ‘mostly women and young girls and boys’; and in 1917, when ‘many thousands’ attended, ‘the majority of the visitors were young men and girls’. There was, for young women, the assurance not only of safety in numbers but also in a customary routine and, from 1914, the presence of disciplined young men. Moreover, the time of year and the proximity to Dublin (or to families in the locality) allowed them to arrive home before dark with the same assurance.

C.J. Woods is co-editor of The writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone, 1763–98 (3 vols, Oxford, 1999–2007).

Read More:Time and place

Music