‘My father was a full-blood Irishman’

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2016), Volume 24RECOLLECTIONS OF IRISH IMMIGRANTS IN THE ‘SLAVE NARRATIVES’ FROM THE NEW DEAL’S WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION (WPA)

By Joe Regan

On 2 November 1938 Mal Boyd sat on his porch in Pine Bluff, Arkansas; he recollected his father’s years as a slave in Texas:

‘Papa belonged to Bill Boyd. Papa said he was his father and treated him just like the rest of his children. He said Bill Boyd was an Irishman. I know Papa looked kinda like an Irishman—face was red.’

Between 1936 and 1938, over 2,300 former American slaves from across seventeen different states were interviewed by the New Deal’s Federal Writers Project (FWP), a subset of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Amounting to over 10,000 typescript pages, the WPA’s slave narratives comprise the largest single written source of US slaves’ personal experiences. The WPA narratives provided surviving former slaves with an unparalleled opportunity to give their personal accounts of their experiences under the institution of slavery. Each narrative provides a microscopic representation of life in the different slave states of the South prior to Emancipation. Although more than 70 years had elapsed between Emancipation and the conducting of the interviews, these narratives also provide rich insights into white society and contain evidence of some slaves’ interactions with Irish immigrants.

Slavery was the economic, social and political foundation of society in the Old South. Irish immigrants understood the potential of wealth generated from slave labour and that slave ownership served as the basis for elevated prestige and respect in southern society. Many Irish immigrants purchased slaves and some succeeded in becoming large planters. Although some Irishmen owned large plantations, thousands of other Irish immigrants laboured in the South. Southern whites, including Irish immigrants, often drank, gambled, stole, and slept with slaves and free blacks. The WPA narratives reveal a legacy of sexual relations between Irish men and female slaves.

Validity and legitimacy

It is important to note that the WPA slave narratives have generated considerable debate among American historians over their validity and legitimacy as reliable sources for understanding the experiences of the enslaved. For example, John W. Blassingame’s The slave community: plantation life in the antebellum South (1972), an influential and pioneering work analysing the personal accounts of former slaves, deliberately omitted the WPA narratives, fearing that reliance on these accounts would provide ‘a simplistic and distorted view of the plantations as a paternalistic institution where the chief feature of life was mutual love and respect between master and slave’. On the other hand, many recent historians, such as Mia Bay, Edward Baptist and Stephanie Camp, have argued the usefulness of the detailed observations recorded by the FWP narratives, and with careful reading they should not be discounted as a source.

Most of the informants had experienced slavery as young children, and many of those interviewed during the Depression years of the 1930s lived in abject poverty. In Tennessee, Maggie Broyles, whose father was ‘a full-blood Irishman’, admitted that she was ‘having a hard time to scratch around and not go hungry’. The childhood experience of slavery and the hardship of the Great Depression were frequently compared, and many recalled their time in servitude favourably. For example, Ransom Sidney Taylor in Charlotte, North Carolina, provided an idyllic picture of plantation life and his former master, John Cane, ‘an Irishman from the North’. Ransom recalled how

‘Mother and Father said he was one o’ the best white men that ever lived. I remember seein’ him settin’ on the porch in his large arm chair. He called me “Lonnie”, a nickname. He called me a lot to brush off his shoes. I loved him he was so good.’

Cane’s slaves always had ‘plenty of something to eat’ and Cane was portrayed as a benevolent master who ‘would not allow anyone to whip his Negroes. If they were to be whipped he did it himself and the licks he gave them would not hurt a flea. He was good to all of us and we all loved him.’ As children under the age of ten, many of the informants had not experienced at first hand the full rigours of plantation routine and discipline.

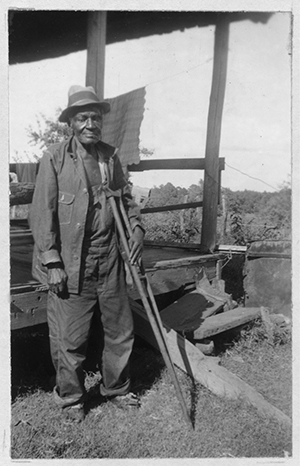

Above: Litt Young from Texas, aged 87. He was a former slave of Martha Gibbs, ‘a big, rich Irishwoman’. (Library of Congress)

The WPA narratives included the testimony of an estimated 3% of former slaves still alive in the US. The representativeness of the accounts has been questioned owing to the disproportionate representation of information recorded. For example, Arkansas, which never had more than 3.5% of the US slave population, accounts for over 33% of the WPA’s collected narratives. The most serious source of distortion in the narratives, however, came from the interviewers, the overwhelming majority of whom were white southern males. North Carolina, South Carolina and Alabama, for example, employed a total of one black interviewer, compared to Florida, which employed ten. The lack of black interviewers influenced the responses provided by the former slaves. During the 1930s, the Jim Crow system of racial segregation and white supremacy was securely entrenched and pervaded everyday life in the US South. Throughout this period, sharecropping and lynching demonstrated the nature of power in the South. White collectors often adopted patronising and condescending tones. Some informants mistook their interviewer for a government representative who might aid them economically and calculated their responses in an attempt to gain favour. For example, Josephine Stewart, aged 85, in Blackstock, South Carolina, concluded her interview with a plea, ‘Please do all you can to get de good President, de Governor, or somebody to hasten up my old age pension dat I’m praying for’. Josephine’s master’s mother-in-law, ‘Miss Anne Jane Neil’, was ‘a Irish lady, born in Ireland across de ocean’. A questionnaire was devised by John Lomax, National Advisor on Folklore for the WPA, but it was partially or completely ignored by the collectors. As a result, the quality of the accounts recorded is uneven and provides contradictory information about the nature of American slavery. The frankness of the much-quoted Martin Jackson of San Antonio, Texas, is not to be found in all accounts: ‘Lots of old slaves closes the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery. When the door is open, they tell how kind their master was and how rosy it all was.’

Irish interactions

The slave narratives reveal that slaves encountered Irish immigrants at all levels of southern society, from planters to manual labourers. In Raleigh, North Carolina, former slave Charity Austin remembered how ‘we children stole eggs and sold ’em durin’ slavery. Some of de white men bought ’em. They were Irishmen and they would not tell on us.’ In 1861 Angie Boyce was born into slavery in Kentucky. Her mother, Margaret King, attempted to reach her freed husband in Indiana. She was arrested, however, and placed in the Louisville jail and ‘lodged in the same cell with [a] large brutal and drunken Irishwoman’. Enraged by the crying of Margaret’s baby and ‘crazed with drink’, the Irishwoman threatened to ‘bash its brains out against the wall if it did not stop crying’.

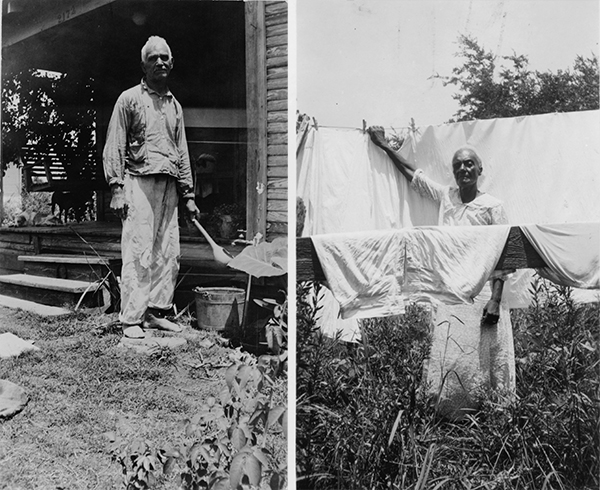

Above: ‘In those days all the slaves had the religion of the master,’ recalled Donaville Broussard (left), a former French-speaking slave from Louisiana. ‘The priest came and held Mass for the white folks sometimes.’ Orelia Alexie Franks (right) was also raised ‘where everybody talk French’. She declared how ‘I used to be a Catholic but now I’s a Apostolic’. (Library of Congress)

The interactions between slaves and Irish immigrants varied considerably, but those who laboured under an Irish overseer or were owned by an Irish master found that the latter could be just as ruthless as native-born white southerners. At the age of twelve Moses Mitchell was sold ‘to an Irishman named John McInish in Marshall [Texas] for $1,500’. His mother and baby sister were left in Arkansas and he never saw either of them again. Investment in slavery was deemed economically prudent and the institution was avidly defended and morally justified by the various Christian churches in the US South, including the Catholic Church. Irish families consciously exploited and profited from the institution of slavery. Litt Young was a former slave of Martha Gibbs, ‘a big, rich Irishwomen and not scared of no man’. She enforced strict routines on her holdings outside Vicksburg, Mississippi. Young observed how his mistress ‘buckled on two guns’ before she went among the slaves and ‘out-cussed a man when things didn’t go right’. The work on Gibbs’s plantation began when the ‘big bell rung at four o’clock’, with the overseer ‘standin’ there with a whippin’ strap if you was late’. Cotton quotas were set for individual slaves and the ‘last weighin’ was done by lightin’ a candle to see the scales’. Any picker ‘not getting his task’ got a whipping. Litt recalled how her second husband, Dr Gibbs, before the Civil War suggested to his wife that ‘you oughtn’t whip them black folks so hard’. Martha was quick to order her husband to ‘Shut up’ and ignored his pleas. In 1863, after the fall of Vicksburg to Union forces, Martha Gibbs moved to Confederate-controlled Texas with her slaves. On their forced march Gibbs had hired Irishmen as guards, and Litt recalled that when they made camp at night ‘they tied the men to trees. We couldn’t git away with them Irishmen havin’ rifles.’ In Nashville, Tennessee, Emma Grisham remembered when the ‘fightin’ got so heavy mah white people got sum Irish people ter live on de plantation, en dey went south, leavin’ us wid de Irish people’.

Wherever slaves worked on large plantations in the antebellum South, white men were typically hired as overseers to supervise and discipline the enslaved workforce. Among these were Irish overseers who undertook managerial positions on southern plantations. Violence was inherent in the plantation system, since it was the most successful method for slaveholders and overseers to resolve labour disputes. When an overseer failed to dominate the slaves, he failed to keep his job. Some overseers resorted to violence, sexual assault and the rape of slave women to assert their dominance and power. The sexual abuse of female slaves by overseers went largely unchecked. Most white men cared little for the consequences of their sexual relations with the slaves, but the children born from these relations left a lasting legacy. For example, in Woodward, South Carolina, John C. Brown stated that his wife Adeline Brown’s father was ‘a full blooded Irishman’ who was the overseer for ‘Marse Bob Clowney’. John divulged how the Irish overseer ‘took a fancy for Adeline’s mammy, a bright ’latto gal slave on de place. White women in them days looked down on overseers as poor white trash. Him couldn’t git a white wife but made de best of it by puttin’ in his spare time a-honeyin’ ’round Adeline’s mammy. Marse Bob stuck to him, and never ’jected to it.’ The sexual abuse of slaves ranged from acts of punishment to forced reproduction and concubinage. Planters tolerated their overseers’ sexual discrepancies, since they resulted in the birth of children like Adeline, a natural increase in the slaveholders’ property. In Missouri, Betty Brown stated that her mother had five children before Emancipation: ‘Our daddy; he wuz an Irishman, name Millan, an’ he had de bigges’ [whiskey] still in all of Arkansas. Yes’m he had a white wife, an’ five children at home, but mah mammy say he like huh an’ she like him.’ There were also some genuine relationships, which demonstrated kindness and affection between slaves and Irish immigrants. For example, Michael Morris Healy in Georgia was an Irish slaveholder who took extraordinary measures to secure the freedom of his slave children. In 1875 one of his sons, James Augustine Healy, became the bishop of Portland, the first black Roman Catholic bishop ordained in the US.

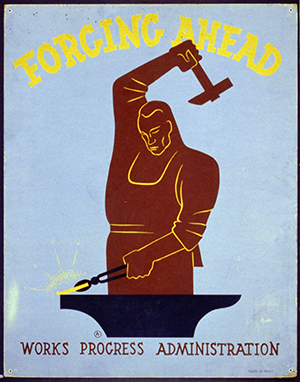

Above: ‘Forging ahead’—the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed some five million Americans between 1934 and 1943. (Library of Congress)

Conclusion

The presence of black Irish Americans has received limited attention from historians of the Irish diaspora, and the WPA slave narratives are an important but neglected source for understanding the ambiguous relationship between the Irish and African Americans in the US. The evidence provided by the former slave narratives led one of the leading twentieth-century historians of the South, C. Vann Woodward, to remark that, given ‘the mixture of sources and interpreters, interviewers and interviewees, the times and their “etiquette”, the slave narratives can be mined for evidence to prove almost anything about slavery’. Just as the plantation records and the writings of planters cannot be used without caution, the slave narratives, like all primary sources, have their usefulness and limitations for understanding the past. The WPA slave narratives are too valuable to be left aside by historians and remain an important source for understanding American slavery. They also offer a new perspective on an under-studied part of the Irish story in America.

Joe Regan has recently completed a Ph.D on Irish immigrants in the US slave South at NUI Galway.

FURTHER READING

J. Ernest (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the African American slave narrative (Oxford, 2014).

D. Gleeson, The Irish in the South, 1815–1877 (Chapel Hill, 2001).

L. Hill, ‘Ex-slave narratives: the WPA Federal Writers’ Project reappraised’, Oral History 26 (Spring 1998), 64–72.

C. Van Woodward, ‘Review: History from slave sources’, American Historical Review 79 (April 1974), 470–81.

Read More:

WPA’s ‘slave narratives’