Exporting Magna Carta: exclusionary liberties in Ireland and the world

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2015), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 23In a rush of commemorative activity this summer, we have been enjoined to recall that Magna Carta (‘the Great Charter’)—whose 800th anniversary fell in June 2015—announced a fundamental principle of the rule of law: even sovereigns should be subject to the law of the land. Magna Carta is credited with being the first effective check in writing on arbitrary, oppressive and unjust rule—in a word, on tyranny.

By Peter Crooks

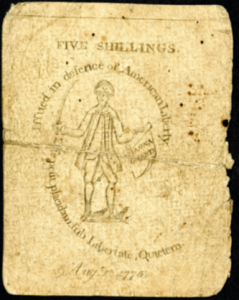

The geographical distribution of Magna Carta 800 commemorations is significant. Magna Carta’s fame spread as England, later Britain, girdled the globe from the seventeenth century onwards. Consequently, it is in the former white dominions of the British Empire—and, especially, in the United States of America—that Magna Carta is most fervently venerated as a beacon of liberty. During the American War of Independence, revolutionaries depicted George III as a tyrant trampling on their birthright to the English liberties enunciated in Magna Carta. Within months of his famous ‘midnight ride’ of April 1775, the revolutionary and silversmith Paul Revere engraved a new seal for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts showing an American brandishing a sword in his right hand and a copy of ‘Magna Charta’ in his left. Fundamental principles associated with Magna Carta were later enshrined in the American Bill of Rights (1791). A panel in the bronze doors of the US Supreme Court, cast in 1935, depicts the sealing of Magna Carta. In 1957 it was the American Bar Association that erected a memorial at Runnymede, the Thames-side meadow where Magna Carta was sealed in June 1215.

Fourteenth-century illumination of ‘bad’ King John hunting a stag. (British Library)

‘Bad King John’

The document we know as ‘Magna Carta’ was sealed on 15 June 1215 by King John of England (1199–1216). It was a royal charter—a legal instrument in which the king granted specified rights, written out in Latin on parchment and authenticated with the royal seal. Unlike most charters, Magna Carta was not conceded by the king of his own will. Rather it was extracted from a reluctant and resentful John by his rebellious barons. John was a notoriously bad king. ‘Foul as it is, Hell itself is defouled by the foulness of John’, wrote an English chronicler after John died. Over a century later the stench of John’s foul reputation lingered in Ireland. The Dublin chronicler from the Dominican Priory of St Saviour, recalling the tumultuous events of John’s reign, referred to the king as a ‘tyrant’.

In one of Magna Carta’s most famous chapters, John was forced to promise not to levy taxes without consent. Needless to say, the barons of 1215 were not chanting ‘No taxation without representation’. But the animating principle of counsel and consent bore fruit later in the thirteenth century in the nascent institution of parliament. The king also undertook not to imprison, dispossess or outlaw his men except by the lawful judgement of peers—principles we now consider the cornerstone of due process of law and trial by jury.

As soon as John was able to do so safely, he repudiated the charter of Runnymede. How, then, did Magna Carta survive to be exported as an artefact and icon of global significance? The saviour of Magna Carta was William Marshal (d. 1219), earl of Pembroke and lord of Leinster, famed as the greatest knight in Christendom. William Marshal became regent of England after King John died in October 1216, leaving as his heir a nine-year-old boy, Henry III (r. 1216–72). In an effort to bring an end to the conflict that had engulfed England, Marshal reissued the charter of Runnymede on 12 November 1216. It was this version of the charter that was sent to Ireland for observance on 6 February 1217.

The charter reforged: ‘Magna Carta Hiberniae’

Detail from the 1215 Charter of Runnymede from the Liber Niger (‘Black Book’) of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin.

The document described by President Higgins as Magna Carta Hiberniae (‘Great Charter of Ireland’) bears the same date of 12 November 1216. But the text differs from its English exemplar. There are a small number of minor, but cumulatively significant, changes. Where the English charter refers to the kingdom of England, the text of Magna Carta Hiberniae refers instead to ‘Ireland’. Where the English charter refers to the ancient liberties of the city of London, the Irish charter reads: ‘The city of Dublin shall have all its ancient liberties and free customs’. And where the English charter orders the removal of fish-weirs from the River Thames, the Irish charter refers instead to ‘Anna Liffey’.

Magna Carta Hiberniae appeared in the manuscript known as the ‘Red Book of the Irish Exchequer’, a semi-official miscellany compiled for the internal use of the Dublin exchequer, the financial department of English government in Ireland. The Red Book was still extant in June 1922, when it perished in the blaze that engulfed the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI). Magna Carta Hiberniae was, by then, a celebrated document, published by Thomas Leland in 1773, produced in facsimile by J.T. Gilbert in 1879, and published again in the critical edition of early Irish statutes by the PROI in 1907. No one yet doubted that it was a genuine royal charter.

Then, in 1940, Robin Dudley-Edwards called the authenticity of Magna Carta Hiberniae into question. He argued that the Magna Carta transmitted to Ireland in 1217 must have been an unadulterated version of the English text. Despite these revelations, the myth of the Magna Carta Hiberniae has proved resilient, and the old orthodoxy that a version of Magna Carta was tailored specifically for Ireland in 1217 is rehearsed in the most recent and authoritative works on the making of Magna Carta in England.

Admittedly, the textual history of Magna Carta in the century after 1215 is extremely complicated. The key problem is what we might call ‘version control’. King John’s charter of Runnymede was, as we have seen, soon superseded by the charter of Henry III, issued in November 1216 and sent to Ireland in February 1217. When the charter was again reissued in November 1217 it was split into two. The chapters relating to the royal forests were issued as a separate ‘charter of the forest’. The remaining chapters formed a longer document that was soon known as the ‘great’ (in the sense of ‘large’) charter—hence ‘magna carta’. A near-definitive version of Magna Carta was issued in 1225. But when in 1297 Edward I was forced to reissue and confirm Magna Carta, his ministers had difficulty locating an accurate version of the 1225 text from which to make their copies.

Ireland shared in this complex textual tradition. By the later thirteenth century the English legal profession was well developed both in England and Ireland, and there was a growing book trade in compendia of English statutes. One such digest of legal material survives in the manuscript codex known as the Liber Niger (‘Black Book’) of Christ Church Cathedral, which contains a copy of King John’s 1215 charter of Runnymede and a series of later statutes. The text was probably brought to Dublin by an Augustinian canon, Henry le Warre or ‘Henry of Bristol’, who became prior of Holy Trinity (Christ Church) in 1301. The section of the Liber Niger containing Magna Carta includes many documents of legal interest. John’s 1215 Magna Carta is followed by a text purporting to be the reissue of 1217. In fact, this is a hybrid Magna Carta, conflating elements of both the 1217 and 1225 charters. Nevertheless, however slapdash the copying of the scribes, all these were versions of Magna Carta authorised by English kings.

Magna Carta Hiberniae is an entirely different beast. It was an unofficial adaptation of the original charter of November 1216, and a rather clumsy one at that. Medieval copyists were not above ‘improving’ or updating the texts on which they worked. Magna Carta Hiberniae was probably the work of an anonymous exchequer official working in Dublin in the early fourteenth century, whose ‘improvements’ to the 1216 Magna Carta made it relevant to Irish local conditions.

Magna Carta Hiberniae is an entirely different beast. It was an unofficial adaptation of the original charter of November 1216, and a rather clumsy one at that. Medieval copyists were not above ‘improving’ or updating the texts on which they worked. Magna Carta Hiberniae was probably the work of an anonymous exchequer official working in Dublin in the early fourteenth century, whose ‘improvements’ to the 1216 Magna Carta made it relevant to Irish local conditions.

For lawyers, the spuriousness of Magna Carta Hiberniae is rather awkward. The ongoing Statute Law Revision Programme has purged from Ireland’s statute book many redundant statutes, but the 2007 Act specifically names Magna Carta Hiberniae as a retained statute. Our enterprising and anonymous ex-chequer clerk could scarcely have imagined that his new and improved Magna Carta would still be the ‘law of the land’ 700 years after he started tinkering with the text!

For historians, Magna Carta Hiberniae provides a classic case in manuscript form of colonial mimicry and identity formation. On the one hand, the manuscript provides evidence of a strong ‘Magna Carta’ tradition in Ireland, mirroring developments in England. On the other, it provides evidence of the English

settlers in Ireland making Magna Carta their own.

Exclusionary liberty

One aspect of Magna Carta’s history that has received less attention than it deserves is the exclusionary nature of its liberties. Magna Carta was, from the first, a ‘rich man’s charter’ that entrenched the interests of a free, male, landed class. Only gradually were its famous provisions, originally reserved to ‘all freemen’, extended to ‘all men of whatever estate or condition’ (that is, whether free or unfree). Exported to Ireland, Magna Carta took on the added valency of racial animus. The liberties of Magna Carta were English liberties. They served to define the English settlers against the native Irish population. By the late thirteenth century, if not earlier, persons deemed to be ‘of Irish birth and blood’ commonly found it necessary to purchase an individual charter of liberty from the crown if they wished to be ‘free and quit of Irish servitude’.

Magna Carta’s role as a totem of English liberty in Ireland was overtaken in the later fourteenth century by the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which notoriously prohibited marriages and other forms of social and cultural interaction between English and Irish. The manuscript evidence for the Statutes of Kilkenny is problematic (there are no surviving fourteenth-century manuscripts), but there are indications that in its original form the first clause of the Statutes confirmed that ‘all the art-icles contained in the Great Charter of the King shall be in all points held firm and established’. Certainly, in 1410 Magna Carta and the Statutes of Kilkenny were confirmed in the same act of the Irish parliament, which was (let us not forget) an assembly representative only of the English colonists. Magna Carta thus came to be folded into the Statutes of Kilkenny to create a new set of exclusionary liberties now described with increasing regularity as the ‘liberties of the land of Ireland’.

This racialised and exclusionary history of English liberty in later medieval Ireland prefigured the later export of Magna Carta over the oceans, when the extension of Britain’s ‘empire of liberty’ was predicated upon the extermination, dispossession or disenfranchisement of ‘native’ peoples who were deemed too uncivilised or primitive to be admitted to the benefits of English law.

Peter Crooks is Lecturer in Medieval History at Trinity College Dublin.

Further reading

D. Carpenter, Magna Carta (London, 2015).

R. Dudley-Edwards, ‘Magna Carta Hiberniae’, in J. Ryan (ed.), Féil-sgríbhinn Eóin Mhic Néill: essays and studies presented to Professor Eóin MacNeill on the occasion of his seventieth birthday (Dublin, 1940), 307–18.

J.P. Greene, Exclusionary empire: English liberty overseas, 1600–1900 (Cambridge, 2010).

N. Vincent, Magna Carta: a very short introduction (Oxford, 2012).