The executions after the Easter Rising

Published in Editorial, Issue 3 (May/June 2016), Volume 24By Joseph E.A. Connell Jr

Upon his arrival on Friday 28 April 1916 to take command, Major-Gen. Sir John Grenfell Maxwell first issued a proclamation indicating that he would take all measures necessary to quell the Rising. His second command was to have a limepit dug in the yard of Arbour Hill Prison (large enough for 50 bodies, it was claimed), and that is where those executed in Dublin were buried. (After his execution in Cork on 9 May 1916, Thomas Kent was buried in the grounds of the Military Detention Barracks and was reinterred in Castlelyons in 2015. Roger Casement was buried in Pentonville Prison following his hanging there on 3 August 1916 and was reinterred in Glasnevin Cemetery in 1965.)

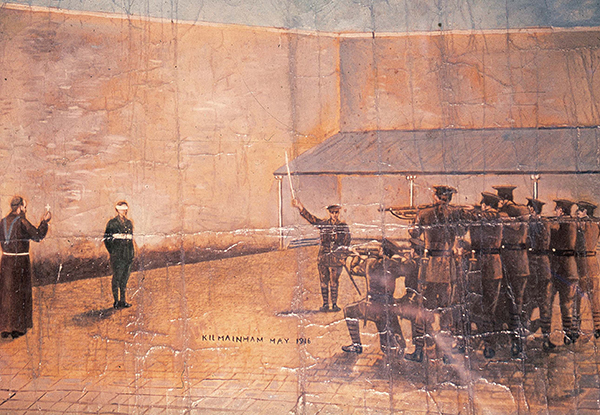

The executions of the fourteen leaders in Dublin took place in the stonebreaker’s yard of Kilmainham Gaol from 3 to 12 May. Maxwell ordered that the men were to be certified as dead by a medical officer and have a name label pinned to their breasts. The bodies would then be removed immediately to an ambulance, which, when full, was to drive to Arbour Hill, where they were to be put in a grave alongside one another, covered in quicklime and the grave filled in. One of the officers with the party was to keep a note of the identity of each body that was placed in the grave, and a priest was to be available to attend ‘the funeral service’.

Each of the men’s families requested that their bodies be released to them for burial. But from the outset Gen. Maxwell was determined that the bodies of the executed men would not be returned to their families. He feared that ‘Irish sentimentality will turn those graves into martyrs’ shrines to which annual processions etc. will be made. [Hence] the executed rebels are to be buried in quicklime, without coffins.’

As a ‘reward’ for their gallantry, troops from the Sherwood Foresters, the regiment whose ranks were so decimated at Mount Street Bridge, were chosen to form the firing squads. Brigadier J. Young was in charge at Kilmainham and laid down the procedures; the first prisoner to be executed was paraded at 3.30am to face a firing squad of twelve men. The commander of the firing squad was Major Charles Harold Heathcote, second-in-command of the regiment. While Major Heathcote was identified as the commander, the regiment followed the custom of not identifying the men who were in the firing squad, and the regimental records have no listing of the squad members.

As is customary in firing squads, eleven of the soldiers had live rounds in their weapons, while one round was a blank. The officers loaded the weapons for the soldiers, so no soldier knew whether his weapon contained the blank round or a live one. If necessary, the officer commanding shot the prisoner in the head with a handgun as the coup de grâce.

The graves are located under a low mound on a terrace of Wicklow granite in what was once the old prison yard of Arbour Hill Barracks. Behind the pit where they are entombed is a wall on which the Proclamation of the Irish Republic is inscribed in Irish and English. On the prison wall opposite the grave site is a plaque listing the names of others who gave their lives in 1916. The current memorial was started in 1955, and the grave is surrounded by limestone kerbing into which the names of those interred are incised in Irish at the head and in English at the bottom. Michael Biggs, a Dublin letter-cutter and sculptor, carved the 4,800 four-inch letters of the Proclamation, beginning in 1959.

Joseph E.A. Connell Jr is the author of Who’s who in the Dublin Rising (Wordwell Books).

Above: Kilmainham, May 1916—contemporary painting, artist unknown. (National Museum of Ireland)