‘Erin cordially welcomes the Empress’:Elizabeth of Austria-Hungary in Ireland, 1879 and 1880

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2011), Volume 19

Portrait of Empress Elizabeth of Austria in dancing dress, 1865, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

Lord Spencer, a former lord lieutenant and avid huntsman, invited Elizabeth, wife of the Emperor Franz Josef, to Ireland. Being keen on hunting, she willingly accepted and it was arranged that she should stay in Summerhill House, home of Lord Longford, in Kilcock, Co. Meath. As this was a private visit she used her minor title, Countess Hohennembs. She arrived in Dublin on 22 February 1879, having travelled from Dover to Holyhead by special train and then on the steam-packet Shamrock. In the imperial party were Prince Rudolf Lichtenstein, Count Larisch, her physician Dr Lanyi and twenty others. Captain George ‘Bay’ Middleton, considered one of the best horsemen in England, acted as her master-of-horse.

Greeted by large crowds

Word got out and she was greeted by a large crowd in Dublin under the banner ‘Erin cordially welcomes the Empress’. The lord mayor welcomed her and a little girl presented a bouquet of flowers. Cheering crowds gathered as her train passed through Clonsilla, Lucan, Leixlip and Maynooth. At Kilcock a red carpet was rolled out and Austrian flags flown. On the last leg to Summerhill, two triumphal arches stretched across the road and another crowd welcomed her. Being an empress, Elizabeth took over the house, allowing Longford to remain as her guest. A room was made over into a Catholic chapel and a telegraph was set up so that she could communicate directly with her husband, Franz Josef.

The empress hunted often in England and her twelve hunters were brought to Ireland. Middleton killed three of them trying to get them used to the notorious Irish ditches. The empress, on the other hand, adapted quickly to the local style of hunting and the Irish scene. A favourite horse was called ‘St Patrick’ and she owned an Irish wolfhound called ‘Shadow’. On 17 March she even wore a sprig of shamrock. On different days she rode with the Ward Union, Royal Meath Fox Hounds Club and Kildare Fox Hunt Club, known as the ‘Killing Kildares’. Not only the local gentry but also notable guests from England joined her, such as the duchess of Marlborough and Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill (parents of Winston).

She caused a great stir and her activities were followed with keen interest by the local and national press. For example, on 4 March 1879 the Irish Times reported:

‘The Empress riding Mr Morrogh’s famous mount, Ward Union, now more famous than ever, was in front from find to finish, and one of the brightest days in the annals of the hunt was wound up by an imperial luncheon, to which all hunting men were bidden.’

People came out in droves on foot and on horseback to see her, and every ditch and hedge she jumped was crowded with spectators. In one case up to 500 horsemen showed up to watch her. The Irish Times reported that on St Patrick’s Day

‘The meet was at Culmullen crossroads and a triumphal arch was erected close to the post office in honour of the occasion with “Welcome to the Empress” inscribed upon it in large characters. The concourse of people on horses, in carriages, and on “shank’s mare” was enormous, but notwithstanding the crowd, order was well kept.’

The locals were impressed by her lack of ostentation and her prowess as a horsewoman. Her visit brought great business to local tailors, hairdressers and barbers, as people put on their finery to see her. It was not all riding after hounds, as she was often entertained by the local nobility and she made her presence felt in other ways. For example, St Patrick’s Church in Curtlestown, near Enniskerry, owns a set of Stations of the Cross donated by her. She had been to dinner with Sir Frederick Trench in nearby Heywood House.

Political tensions

Elizabeth’s stay in Ireland brought political tensions to the fore. The duchess of Marlborough was the empress’s guest, but her husband, as lord lieutenant, had the responsibility of reporting on her to the government. He expressed grave concern at the enthusiasm with which she was greeted. Here, after all, were crowds of Catholic peasants cheering a Catholic empress representing an empire that could claim continuity from the first Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne. In contrast, Victoria had only been an empress (of India) for a few years. The nationalist press warmly welcomed her, stressing that this empress was at home among the Irish people. The Hapsburg Empire had its own problems with nationalism and in 1867 had had to establish the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. It was well known that Elizabeth sympathised with the Hungarian cause. Might she not also favour the Irish one? Her husband, Franz Josef, was not too happy either when he heard reports about the kind of risks she was taking. Hunting in Ireland was pretty wild and the empress did not hold back. She once led a hunt at full gallop for 40 minutes. On another occasion she was thrown from her horse but immediately remounted, to the delight of the spectators.

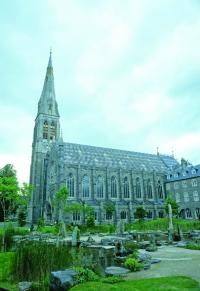

St Patrick’s Collegiate Chapel, Maynooth—on 24 February 1879 the Ward Union Hunt, accompanied by Elizabeth, chased a stag into the building, then under construction. (NIAH)

The stag in the chapel

On 24 February the Ward Union Hunt, accompanied by Elizabeth, chased a stag into the grounds of St Patrick’s College, Maynooth. A new chapel was being built (see ‘Gems of architecture’ in HI 19.2, March/April 2011) and the workmen had opened a gap in the wall, across which they put a makeshift gate. When the elderly janitor saw the stag pursued, he opened the gate and let the animal in. Some of the workmen intervened and rescued it from the hounds. Moments later, the hunters arrived, led by the empress. She must have presented an exotic sight. At 43 she was still stunning, with dark chestnut hair and an extremely thin waist (a feature highly prized among Hapsburg women).

The acting president of the college, Dr William Walsh, a future archbishop of Dublin, arrived on the scene to greet the imperial visitor. The stag, meanwhile, was let free, presumably to be hunted another time. Lord Spencer made the introductions and Walsh offered the party refreshments. He invited the empress to return formally at a later date. She suggested coming to Mass the following Sunday. On the day, she arrived in a brougham-and-four, with her entourage. After Mass she toured the college, gave Walsh a gold ring set with an olivine stone as a souvenir and persuaded him to give the students two days off.

Elizabeth left Ireland on 23 March 1879. As with her arrival, her progress was greeted with Austrian flags and cheers from huge crowds that the police had great difficulty in keeping under control. A bottler in Rutland (now Parnell) Square capitalised on her visit by advertising ‘mineral waters as supplied to the Empress of Austria’. In an apparent snub, on her way through England she did not pay a visit to Queen Victoria, using the excuse of hurrying home owing to flooding in Hungary.

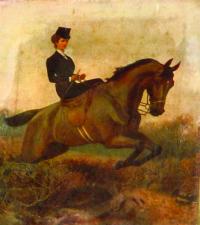

Portrait of Elizabeth riding side-saddle on the horse ‘Merry Andrew’, which still hangs in the Royal Dublin Society. (Gerard Whelan, RDS)

Return visit

She had purchased some Irish hunters and left her English horses with the intention of returning, which she did the following year. Taking the same route, the imperial party, made up much as before, arrived at Summerhill House on 4 February 1880, and she was out hunting the following morning with the Ward Union. As before, huge crowds turned out to greet her with cheers and flags wherever she went. As the hunt passed Fairyhouse racecourse she insisted on jumping all its fences. She dined again at Heywood House.

She returned to Maynooth College, this time presenting it with a statue of St George, one of the few saints to be depicted on horseback. She may have had second thoughts about donating the patron saint of England, and later she endowed the college with a set of vestments of gold cloth with an edging in green silk decorated with gold and green shamrocks and the arms of Austria, Hungary and Bavaria. They were considered too valuable for actual use, however, and were housed in the college museum.

Not welcome back by the British government

Elizabeth left Ireland on 7 March 1880. She could not be seen to snub Queen Victoria a second time and so they had a brief meeting in London. It was her intention to return in 1881, but the British made it clear that she would not be welcome. Bad harvests in 1879 had caused hardship resulting in widespread evictions. The Land League was gaining in strength, coercive measures were introduced and unrest was rife. The government feared that her presence might inflame the situation.

Her visits to Ireland had taken on the appearance of formal occasions, and the enthusiasm for Elizabeth was seen as enthusiasm for a Catholic imperial monarchy at a time when the popularity of the queen was in decline in Britain. While in the long run not significant, at the time her presence was another potentially unstable element in the cocktail of agrarian unrest and strengthening nationalism in Ireland, along with public discontent with Victoria in Britain.

She did not return to Ireland again but left an indelible impression. The empress is remembered in folklore wherever she hunted, and a portrait of her riding side-saddle on the horse ‘Merry Andrew’ hangs in the Royal Dublin Society. In Austria her visit is commemorated in the Coach Museum, Schönbrunn Palace, where there are paintings of her Irish hunters and of her Irish wolfhound, ‘Shadow’. HI

Further reading:

D. Fahey, ‘An Irishman’s Diary’, Irish Times, 20 April 2010.

O. Glaser, ‘The Hapsburgs in Ireland’, in P. Leifer and E. Sagarra (eds), Austro–Irish links through the centuries (Vienna, 2002).

B. Hamann, The reluctant empress (Vienna, 1988).