Elizabeth Bowen’s selected Irish writings

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Book Reviews, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2011), Reviews, Volume 19

Elizabeth Bowen’s selected Irish writings

Éibhear Walshe (ed.)

(Cork University Press, €39, £35)

ISBN 9781859184493

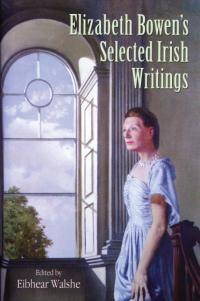

The dust-jacket of Éibhear Walshe’s anthology of the Irish writings of the Anglo-Irish novelist Elizabeth Bowen (1899–1973) reproduces a portrait of her by Patrick Hennessy, standing statuesquely in pale blue evening dress at the top of the grand staircase of her family home at Bowen’s Court, Farahy, north Cork. Bowen’s face, lit by a shaft of creamy sunlight, holds a resolute stare. Painted in 1955, just five years before this eighteenth-century country house was demolished, Hennessy’s photo-realistic style nostalgically freezes time with an interior glimpse of a vanishing ancestral space. In this portrait, displayed in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork, Elizabeth Bowen’s identity is magnified by her ancestral Bowen’s Court. It visually sets the tone for this collection perfectly. Bowen, in the preface to the second edition of her novel The last September, encapsulates the essence of her craft: ‘I am, and am bound to be, a writer involved closely with place and time; for me these are more than elements, they are actors’ (p. 167). Her Irish novels tackle the political and social seismic shifts that shaped an emerging state—the Irish War of Independence in The last September (1929), World War II and Irish neutrality in The heat of the day (1948) and Ireland in the 1950s and emigration in A world of love (1955). Bowen’s fictive writings featuring Ireland may have been sporadic, yet she continually wrote essays and reviews about Ireland, Irish history and Irish writers, both from the Anglo-Irish tradition and Irish literary culture, throughout her career. This anthology gathers together, and chronologically arranges, these critical writings for the first time. Its editor, Éibhear Walshe, author and senior lecturer in Modern English at University College Cork, informs readers, in his comprehensive introductory essay, that as an essayist and reviewer on Ireland ‘Bowen is confident, impressionistic, deft, witty, always in command of her subject and assures her English or American readership of her knowledge and authority on Ireland, its class structures and political system and the nature of social and cultural life in the new state’ (p. 4). Bowen’s complex relationship with Ireland was informed by her Ascendancy ancestry. Her critical writings illustrate what Walshe describes as ‘her own hyphenated identity’ (p. 26). Her north Cork home at Bowen’s Court and ‘big house’ culture, enmeshed within the ancient Irish landscape, thread through her critical writings from the 1930s to the late 1960s. In these she articulates those looming landmarks as manifestations mapping onto her shifting psychological geography. She attempted to write herself and her class into the new, largely Catholic, state by invoking the certainties of a vanishing Anglo-Irish cultural heritage. Bowen wrote best about Ireland in times of war and disorder. Of the five chapters encompassing this anthology’s chronology the fullest is Chapter 2, spanning Bowen’s output during World War II. War drew out divisions both within Ireland and within herself. In the face of violence, Bowen took refuge in her critical intelligence to locate solid ground; conversely, her imagination was moved by a contradictory impulse to explode such permanence. Bowen describes writing under the stress of wartime in the postscript to her essay collection The demon lover (1945), introducing Chapter 3. In the bomb-blasted streets of blitzed London she transforms the salvaging of material possessions from strewn wreckage into a form of spiritual talisman helping to preserve personal identity. Bowen’s Court was her wartime talisman. It was during this period that she completed her evocative family memoir, published in 1942. In her afterword to the 1963 revised edition of Bowen’s Court, introducing Chapter 5, she re-imagines its act of writing, where only the crackling of the radio in the darkened library ‘conducted the world’s urgency to the place’ (p. 204). The house stood ‘in its particular island of quietness, in the south of an island country not at war’ (p. 204). Because of Irish neutrality anxiousness permeates the atmosphere. Bowen’s Court was completed during a period of intelligence-gathering. Extracts from the secret reports on Ireland that Bowen drafted for the ministry of information in London, under her married name of Cameron, are reprinted, alongside her wartime reviews, in Chapter 2. These reports, read by Winston Churchill, present pen-sketches of social and cultural life during ‘the Emergency’. Polemically, Bowen stresses that neutrality was the Irish state’s first free act of political self-assertion. Walshe in his introduction places these subsequently controversial reports within the context of Bowen’s lifelong desire to act as a translator between Ireland and Britain, a desire often thwarted and misguided.Elizabeth Bowen’s selected Irish writings is sensitively edited by a Bowen scholar who comprehensively situates her critical writings within the body of her better-known literary work but does not intrude on Bowen’s voice. Bowen’s Irish writings illustrate the ambivalent position of the Anglo-Irish within the Irish Free State. HI

James G.R. Cronin is a staff member in the School of History and the Centre for Adult Continuing Education at University College Cork.