The Spanish Basque Irish Fishery & Trade in the Sixteenth-Century

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 2001), Volume 9

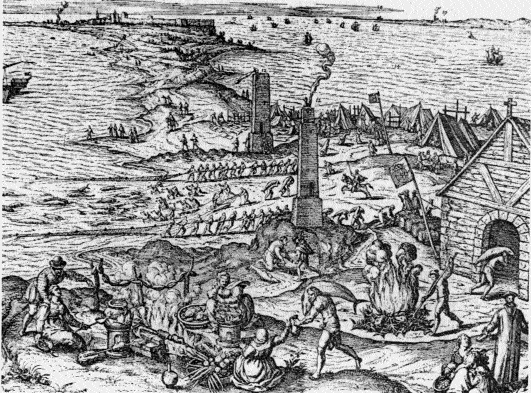

Spanish fishermen catching, smoking and barrelling fish-similar scenes would have been witnessed on the south and west coasts of Ireland.

It is not clear when Basque mariners first began fishing off the coast of Ireland but the ordinances of 1553 of the confraternity of fishermen of the Spanish Basque port of Bermeo indicate that men from there were already fishing in Irish waters by then. Furthermore, in a lawsuit over the fishing voyage of the ship Bárbara of San Sebastián to the Irish coast in 1506 witnesses testified that fishermen from that port ‘have been accustomed to go fishing [in Ireland] from times immemorial’.

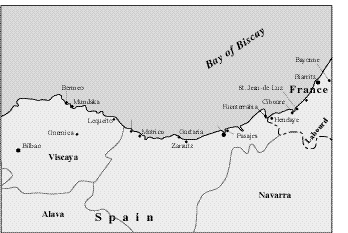

In the early sixteenth century the principal long-distance Basque fisheries were off western and south-western Ireland, largely for hake, conger eel and herring but also for pilchard (Ireland’s most important export in the 1500s) and a whale fishery off the coast of Galicia in north-western Spain. Whereas relatively few details are available concerning French Basque involvement in the ‘Irish fishery’, as it was called, northern Spanish archival sources amply confirm the prominent position of Vizcayans and Guipúzcoans in the fishery. They also confirm that the Irish fishery, along with whaling off Asturias and Galicia—and not the nascent Terra Nova (Newfoundland and Labrador) cod and whale fisheries—were the Spanish Basques’ main offshore fisheries, even in the fourth decade of the sixteenth century.

Scale

Of the sixty-seven ships given in the September 1534 Guipúzcoan shipping survey as preparing for or away on voyages, no less than fifteen, totalling 1,230 tons (an average of eighty-two tons each), equivalent to 11.1 per cent of the total tonnage or 20 per cent of the total number of ships, were away at the Irish fishery in which some other northern Spanish ships, as well as certain English, French and Portuguese vessels, customarily took part every year. In contrast only a couple of Basque ships had sailed to Terra Nova that year. All fifteen ships (eleven caravels ranging from forty to 120 tons and four naos ranging from eighty to 170 tons), crewed by between 250 and 300 men and boys, were from San Sebastián and El Pasaje de Fuenterrabia. To these fifteen Guipúzcoan ships should have been added a number of Vizcayan vessels, primarily from Ondárroa, Lequeitio and Bermeo, while a forty-ton zabra from Deva, Guipúzcoa was in Ondárroa bound for Ireland, apparently for trade and not fishing. The tithe accounts of Lequeitio’s parish church reveal that, beside the local inshore fishery, in most years of peace during the first half of the century up to four vessels were equipped in that port for the Irish fishery, sometimes in association with mariners from Ondárroa, Bermeo and other nearby ports.

Season

That a relatively large fleet of Spanish Basque fishing ships sailed to Ireland in the summer of 1534 means not only that the fishery was still a profitable enterprise for them but also that the ships had not gone to Terra Nova as the two fishing seasons overlapped. At that time ships bound for Terra Nova customarily left in March or April and returned in late August or September, while those going to Ireland left in the summer and usually did not return until November or later. In the 1506 lawsuit over the Bárbara witnesses were asked whether ships normally left San Sebastián for Ireland in June or July and returned in September or by All Saints’ Day (1 November) at the latest. But in another lawsuit witnesses declared that the Irish fishing season ‘was usually from August until Christmas’, while the fifteen Guipuzcoan ships of 1534 mentioned above were expected back ‘by the middle of the month of November, a few [days] more or less’.

Fishing grounds

Witnesses in the Bárbara’s lawsuit also mentioned specific fishing destinations on the rugged and exposed south-western Irish coast from Baltimore in the south (near Cape Clear) to Valencia Island 100 kilometres to the north-west. Records show that this was one of two main Spanish Basque fishing areas in Ireland. The other was almost 400 kilometres north at ‘Calabeq’ [Killybegs] in Donegal Bay.

Present-day Basque inshore fishing boats, similar in length to sixteenth-century pinazas.

According to the master of Bárbara, when he sailed to Ireland in 1506 he first took the ship to the ‘port of Arrisymin’ or ‘Reschin’ in the south-west where he and the crew stayed for forty days but only found ‘very little’ fish. Therefore, at the end of August they sailed to ‘Calaber’ or the ‘island of Calabeq’ where they fished ‘with another eight naos from this [Spanish Basque] coast’. Unfortunately, if the master’s testimony is correct, Bárbara and other ships were lost as they departed for Spain, with Bárbara’s crew barely managing to escape ‘in [their] doublets’. One of the other ships that sailed to the fishery that summer was the caravel Magdalena which left El Pasaje harbour for ‘the ports of Milber and Otelin’. There were good profits to be made in the Irish fishery, hence the considerable interest of entrepreneurs and fishermen alike in those voyages. For instance in the summer of 1529 the caravel María of San Sebastián was chartered for the Irish fishery by Joanes de Villar, also of San Sebastián. The crew caught a total of 3,170 ‘dozens’ of hake and the shipowners’ fifth of the catch from that season alone (less their share of the ‘salt and nets’) came to about 220 ducats, whereas it had cost them 604 ducats to build the caravel.

Organisation

This Basque Irish fishery was a forerunner of the trans-Atlantic cod fishing and whaling ventures to Terra Nova that developed rapidly after 1545: it was a large-scale market-orientated enterprise controlled by merchants; it involved a long period away from the Basque coast at distant fishing grounds and required extensive and complex financing. At one end of the organisational scale was the type of venture that was financed and put together by two or three traders of modest or middling economic standing in conjunction with local master fishermen, almost a form of co-operative undertaking. One such venture was the 1530 voyage of the caravel Trinidad of Motrico, owned by Juan Ochoa de Berriatua. ‘At the request’ of six of the town’s maestres de pinazas [master-owners of open fishing boats] two local merchant-entrepreneurs, Juan de Meçeheta and Juan de la Plaça, agreed to charter Trinidad for the fishery, providing nine pinazas with their crews and loading the vessel with ‘all the necessary victuals of bread, wine and cider, and the equipment for the said fishery’.

On 16 June 1530, an agreement was signed in Motrico’s hospital between Meçeheta and la Plaça and the six master fishermen (acting for themselves and for the ‘companions and sailors’ of their pinazas) in which the conditions for the fishing voyage were laid down. The master fishermen elected Meçeheta and la Plaça as ‘the guardians and captains according to the custom of the fishery’ and gave them power of attorney to conclude the charter-party with Trinidad’s owner and to commit them ‘to fulfil, pay and provide each one of them, for themselves and the people of each pinaza, all the victuals and equipment which is required by each of them for the said fishery’. The master fishermen also empowered the captains to borrow money in their names with which to buy the victuals and equipment as well as to ‘order them hither and thither’ for the duration and best result of the voyage. The captains could put into whichever Irish port they wished ‘consulting with the master fishermen or not’, as was customary, and if the fishermen did not fulfil their part of the agreement they were to lose their shares. A final condition was that no one was to be allowed to take or bring back ‘merchandise’ in the ship unless all agreed and each person had his respective share in the goods. As usual on Basque fishing voyages to Ireland, while one of the charterers or their nominee sailed as captain the shipowner or his appointee sailed as master.

At the other end of the scale was the type of venture dominated by large-scale merchants and their capital. For instance, in 1510 Gregorio de Turbi, a Genoese merchant resident in the French Basque port of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, chartered and fitted out two ships owned by Martín de Yriburu from that same town ‘for this year’s Irish fishery’. On 22 May the two vessels, Catalina (Juanes de Sorravindo, master) and María (Guichet de Rançu, master), were moored in El Pasaje harbour ready ‘to leave with the first good weather that God may give’ and on that day the Genoese signed a contract with his Spanish Basque associate, Juanot de Larrandabuno of San Sebastián. The two men declared that Turbi had invested 1,557 francs and Larrandabuno just over 147 old ducats and by the document they agreed that ‘the profit and loss made…shall be common, halves each, at the risk and fortune of the said Gregorio and Juanot’. In spite of the clarity of the agreement the partnership ended in litigation.

Sixteenth-century stone carving from house in the Basque Country of ship of the same type used in the Irish fishery.

After the ships had returned from Ireland Larrandabuno filed suit against Turbi in Guipúzcoa claiming that Turbi had ‘gone absent’ and had not fulfilled the contract. Larrandabuno demanded to be paid the money he claimed Turbi owed him from fish (mostly conger eel, hake and herring) belonging to the Genoese businessman and that had been embargoed in the ‘cabins…on the beach of the said town of San Sebastán’ to pay his other creditors.

Marketing

The fish caught from Irish waters could be dried either in Ireland or in Basque ports (for subsequent sale in the Iberian interior) as is indicated by a promissory note signed in San Sebastián on 20 May 1506. By way of repayment of an eighty ducat loan from Juan Pérez de Ydiacaiz, a merchant from the inland Guipuzcoan town of Cestona, the master of Bárbara, Juan López de Aguirre, undertook to deliver to Ydiacaiz ‘twenty cargas [a carga comprised fourteen ‘dozens’ of fish] of cured hake from Ireland, half of which dried in Ireland and the other half dried in this land’. This northern European fishery even involved marketing catches in southern Spain and the Mediterranean as is illustrated by a voyage of the new ship Santa Marina, chartered in April 1511 by Juan de Maidana from another Lequeitio entrepreneur, Martín Pérez de Olea, for ‘the Chirgo fishery’ in Ireland. By St Peter’s day (29 June) Maidana, who sailed as captain, was to have loaded the armazón [the victuals and fishing equipment] onto Santa Marina, including ‘six pinazas for fishing hake and one for killing sardines’, two of the six pinazas with five ‘fishing men’ each and four with four men each. In keeping with the custom on these ventures, the shipowner, Olea, was to contribute one-fifth of the cost of the armazón (‘except in the victuals and things for eating’) and to receive by way of payment one fifth of all the profits. He was also to receive one third of the freightage due from any other cargo transported during the voyage (‘as on merchant voyages’). From Lequeitio the ship was to sail to La Rochelle to purchase salt for curing the fish and from La Rochelle to the ‘island of Aran’ (Galway Bay?) where the crew was to fish ‘until the feast and day of Christmas’. Having completed this lengthy period away from northern Spain the ship was to sail to Cadiz where the catch was to be sold, although the charter-party did specify that ‘if the said fish cannot be sold there in that case the said nao should go ahead to any place and part that the said Maidana wishes until reaching Civitavecchia which is next to Rome and there carry out the official unloading’.

Import-export trade

The Basques also traded extensively in Irish ports, exporting iron and other commodities and, besides fish, returning primarily with hides and leather, which together were Ireland’s second most important export in the 1500s. Spain was the principal importer of Irish hides which also found ready markets in France, Flanders and Italy. Around 1503 two merchants from Bilbao and one from inland Vitoria loaded a ship with wine, saffron, sword blades and other goods which they took to ‘St Michael’ [Ballinskelligs, County Kerry] bringing back to Bilbao mainly fish and hides. The tithe accounts of Lequeitio’s parish church for the first half of the sixteenth century register many such trading voyages by local ships to Cork, Waterford and Dublin. One Lequeitio merchant, Pero Sáenz del Puerto, brought ‘a dozen bedelines’ (a type of hide often brought from Ireland) for the town’s parish church. A notarial document records in 1529 three merchants from the same Vizcayan port sending 1,357 iron bars (fourteen tons) in a ship from nearby Motrico to be sold in Dublin or Liverpool or another port ‘of Ireland or England’. The proceeds from the sale were to be used to purchase other merchandise that was then to be taken in the same ship for sale in Cádiz. This is an example of one of the many triangular trades in which Basque merchants had long been involved. The considerable Basque and northern Spanish trade in general with Ireland even in the mid 1500s is no doubt encapsulated in an English report from 1543 which made known that ‘from Limerick to Cork, the Spaniards and Bretons have the trade, as well as the fishing there, as buying their hides, which is the greatest merchandise of this land’. At Bordeaux pre-1550 notarial records document French Basques, but more Bretons and Normans, trading in Irish ports in the late 1400s and early 1500s, almost always carrying in their ships wine for Bordeaux merchants and returning with fish, hides and other goods.

Decline and end

The Spanish Basque cod and whale fisheries in Terra Nova reached their peak during the relatively peaceful quarter century between 1560 and 1585. In the best years the Vizcayan and Guipúzcoan fleet consisted of about forty medium and large ships totalling approximately 9,500 tons and crewed by up to 2,000 to 2,500 men and boys, a high proportion of Spanish Basque fishermen-sailors. Ships that on the cod fishery were away for five or six months between March/April and August/September, while whaling voyages lasted six to eight months between April/May and December/January. The rise of these trans-Atlantic ventures was the principal cause of the almost total ending of the Spanish Basque fishery in Ireland; they yielded greater profits; cod fishing crews did not return from Terra Nova until August at the earliest (and whaling crews later); ships chartered for the Irish fishery had usually left by then. The decline of the Irish fishery is reflected in the tithe accounts of Lequeitio: prior to 1560 (war years excepted) one, two or more fishing voyages to Ireland are recorded annually; after 1560 they are hardly mentioned. The situation regarding Terra Nova expeditions is the exact opposite.

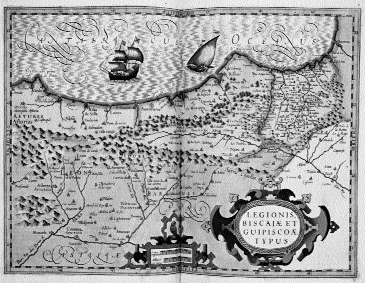

Engraved map of north-eastern Spain and the Basque Country. (Mercator-Hondius atlas, Amsterdam, 1606)

The Vizcayan and Guipúzcoan presence in the waters of north-western Europe was also affected by the increasing hostility of the English towards Spanish subjects after the 1550s. It ceased completely during the long Anglo-Spanish war of 1585-1604. In 1625-26 the Spanish Basque priest and historian, Lope Martínez de Isasti, whose own father had purchased significant quantities of ‘Irish hides’, wrote:

In the past the mariners from this coast of Guipúzcoa used to go to Ireland in small ships to the hake, salmon and herring fishery and to the cattle hide and dried meat trade in which they were successful, without distancing themselves to Terra Nova; and this trade and navigation ceased one hundred years ago [1526] because of English opposition.

Isasti slightly mis-timed the ending of the fishery: in fact it continued for several more decades. Its decline was due not only to ‘English opposition’ but primarily to the phenomenal expansion of the Terra Nova fisheries.

Michael M. Barkham is an independent scholar and museum consultant who holds a doctorate in geography from the University of Cambridge

Further reading:

M. M. Barkham, ‘La industria pesquera en el País Vasco peninsular al principio de la Edad Moderna: ¿una edad de oro?’ [‘The fishing industry in the Spanish Basque Country during the early modern period: a golden age?’], in Itsas Memoria/Revista de Estudios Marítimos Vascos, 3 (2000).

S. Huxley (ed.), Los Vascos en el Marco Atlántico Norte, Siglos XVI y XVII [The Basques in the North Atlantic in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries] (San Sebastián 1987).

A.K. Longfield, Anglo-Irish Trade in the Sixteenth Century (London 1929).

Glossary

caravel: small to medium size ship with two or three masts, lateen or square-rigged or in combination, common in sixteenth-century Spain and Portugal.

nao: three-masted and usually square-rigged ocean-going merchant ship, 70 to 800 tons, 17 to 33 metres in length.

zabra: sixteenth-century vessel used for coastal trade in northern Spain, 30 to 70 tons, 11.5 to 17 metres in length.

pinaza: sixteenth and seventeenth-century inshore north coast Spanish fishing vessel, 8 to 11.5 metres; larger ones with half-decks fore and aft.