The Royal Schools of Ulster

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2009), The Reformation, Volume 17 The State has always been quick to enlist schools as agents of public policy, not least in Ireland, both pre- and post-independence. This was particularly so at the time of the Reformation, when Tudor legislation sought to establish a system of parish elementary schools and diocesan grammar schools throughout the land. These ambitious schemes, whereby the native Irish were to be Anglicised (and Anglicanised), remained largely aspirational, depending on local clerical and episcopal initiatives that were not generally forthcoming. In the eighteenth century there were the ‘charter schools’, founded by George II, generously funded by Crown and parliament to bring up the children of the Irish (largely Catholic) poor as loyal and industrious Protestants, but these too achieved little. The story of the seventeenth-century Royal Free Schools associated with the Ulster Plantation is one of success, however, after an initially unpromising start, and to this day they remain major educational establishments.

The State has always been quick to enlist schools as agents of public policy, not least in Ireland, both pre- and post-independence. This was particularly so at the time of the Reformation, when Tudor legislation sought to establish a system of parish elementary schools and diocesan grammar schools throughout the land. These ambitious schemes, whereby the native Irish were to be Anglicised (and Anglicanised), remained largely aspirational, depending on local clerical and episcopal initiatives that were not generally forthcoming. In the eighteenth century there were the ‘charter schools’, founded by George II, generously funded by Crown and parliament to bring up the children of the Irish (largely Catholic) poor as loyal and industrious Protestants, but these too achieved little. The story of the seventeenth-century Royal Free Schools associated with the Ulster Plantation is one of success, however, after an initially unpromising start, and to this day they remain major educational establishments.

One school per escheated county

The original proposals envisaged six schools, one for each of the escheated counties, but the school in County Coleraine (later renamed Londonderry) owed its existence to the Irish Society and has never been numbered among the ‘Royal Free Schools’. A crucial distinction between the Royal Schools and other Crown foundations was that they were intended for the sons of the Protestant undertakers and chief servitors of the newly settled territories, and not for the dispossessed Catholic population. As early as 1607, George Montgomery, bishop of the combined sees of Derry, Raphoe and Clogher, claimed that, having spent the best part of a year in the most northerly and ‘most barbarous’ part of Ulster, he was certain that unless the education of the youth of the country ‘in learning and loyalty’ was taken in hand no improvement in the situation could be expected. He called for the establishment of free schools, and when the lord deputy, Sir Arthur Chichester, sought a royal warrant in respect of those Ulster lands to be escheated for planting, he bore the bishop’s proposal in mind. Similarly, Sir George Carew had been made aware by the high sheriff of County Tyrone of the urgent need for educational provision for the sons of the planters and their tenants, there being ‘a great defect of schools in those parts for the instruction of their youth’. Consulting with the local gentry, the high sheriff found them not only willing but desirous of having ‘schools for that purpose settled amongst them’.

The ‘orders and conditions’ governing the Plantation, therefore, included the instruction that each county should have schools for the instruction of youth, land being set aside for the purpose. Nonetheless, however desirous the new settlers may have been of schools for their sons and those of their tenants, little happened for several years, doubtless in part owing to the disruption caused by Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s rebellion. Any attempt to closely follow the fate of those thousands of escheated acres initially allotted for the support of schools is fraught with difficulty, and complaints abounded about the alienation of lands supposedly dedicated to schools. Despairing of the local magnates moving on the matter, and aware that attempts had been made to put these estates to other purposes, from 1612 Chichester instigated a change to the original plan, conveying the management of school lands to Ulster’s bishops. Letters patent made it clear that the king had transferred this responsibility to them ‘as men whose function and quality it is most proper to be careful’.

In 1612 Henry Ussher of Armagh (not to be confused with his internationally renowned successor, James) had reported on schools planned ‘according to royal command’ for Armagh and Dungannon, both of which lay within his diocese. These schools were to be provided with schoolmasters, ‘religious and learned men’ appointed by the archbishop, who would hold office during their good behaviour. While in office, they would hold leases of the school lands, confirmed by the dean and chapter of Armagh. Pending the appointment of schoolmasters, the rents accruing from the school lands were to be used to build a schoolhouse. In 1614 the king, learning ‘that there are not as yet any further schoolhouses erected’, directed the bishops to proceed with applying the rents to building schoolhouses and to appointing masters.

First schoolmasters appointed

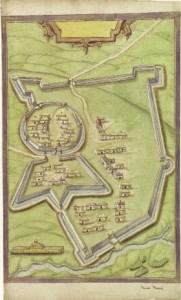

Richard Bartlett’s 1601 map of the fort at Mountnorris, between Armagh and Newry (see reviews, p. 78). While we are not certain of its precise location, the likelihood is that the school was within its protecting walls. (National Library of Ireland)

However tardily, the schools eventually came into being with the appointment of the first schoolmasters. In 1609–10 Thomas Lydiat, a graduate of Oxford, was appointed to Armagh and John Robinson took up the Cavan post. Within a few years John Bullingbroke became master of Dungannon, Geoffrey Middleton of Lisnaskea (later sited at Portora), and Bryan Moryson took charge of Donegal (later Raphoe). These men were all well qualified for the task, most as graduate clergy of the Established Church of Ireland, while Moryson (or O’Moryson) was described as an Irish native who had conformed and ‘a very good humanist’. The lord lieutenant’s order appointing Robinson to Cavan referred to the setting aside of a ‘certain proportion of land for free schools to be erected there for the future good and civil education of the youth in general of the province of Ulster’. The royal letter patent making the appointment to Dungannon stated the intent ‘that the youths of this realm may be educated in literature and knowledge of true religion to the end that they may learn their duty towards God and true obedience toward us’.

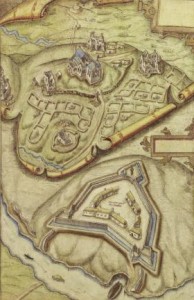

Not surprisingly, the schools were based on the lands of those proprietors most closely associated with the settlement, in several cases moving after some years from their original sites. For example, while the earliest records of the school for County Fermanagh mention the Lisnaskea lands of Sir James Balfour, it subsequently moved to Sir William Cole’s newly established borough of Enniskillen, at Portora, outside the town. Just as Trinity College, Dublin, began life on the lands of a suppressed religious house, for over a century Armagh school occupied a former Columban abbey, following an earlier period at Mountnorris. Dungannon Royal Free School is thought to have started life near the fortress of Mountjoy, Co. Tyrone. But whatever progress may have been made, Wentworth, writing to Archbishop Laud in 1633, lamented that the schools in fact fell far short of their original objectives:

‘The schools, which might be a means to season the youth in virtue and religion, either ill-provided, ill-governed in the most part, or which is worse, applied sometimes underhand to the maintenance of popish schoolmasters; lands given to these charitable uses, and that in a bountiful proportion, especially by King James, of ever blessed memory, dissipated, leased forth for little or nothing, concealed contrary to all conscience, and the excellent purposes of the founders.’

Not free

Lord Deputy Thomas Wentworth, first earl of Strafford, writing to Archbishop Laud in 1633, lamented that the schools fell far short of their original objectives. (National Portrait Gallery)

From the outset, parents paid quite substantial boarding and tuition fees in the Royal Schools. Official reports enable us to discern a pattern from the early eighteenth century. In addition to the annual fee, sometimes charged quarterly, there was usually an ‘entrance fee’. In the case of Portora this came to five guineas for boarders and one and a half guineas for day pupils, the boarders paying 32 guineas per annum and the day pupils six guineas. Raphoe, a somewhat smaller school and with less impressive premises at the time, charged boarders (some of whom lived with local farmers) five guineas on entrance and subsequently 26 guineas per annum. The small number of day pupils paid one guinea on entrance and four guineas per annum. Incidentally, in considering these figures it is important to note that the school year was much longer than today, and that parents of boarding pupils were spared the cost of maintaining their sons at home for the greater part of the year.

Several parliamentary enquiries suggest that the masters were academically qualified, mainly classics graduates, as befitted men whose teaching would largely be confined to Latin (and occasionally Greek) authors, English literature and the Scriptures. Only in the late nineteenth century did mathematics, science and modern languages (generally French or German) find a regular place in the school curriculum. In 1881 the Rosse report on endowed schools identified a factor which undoubtedly inhibited the development of Ulster’s Royal Schools (and indeed all Irish grammar schools), stating that ‘. . . all the nobility and the great majority of the gentry send their sons to English or foreign schools’, institutions supported by large numbers of pupils and high fees that could offer an education superior to any available in Ireland. The report recommended an improvement in the quality of grammar-school teaching in Ireland. When in due course this came about through the wider provision of university education, the advantages of patronising local schools became clear and the balance was redressed in favour of the local foundations. They have changed enormously, offering as they now do a broad curriculum in a co-educational setting and in modern buildings with facilities not imagined by their founders. Nor could their original patrons have foreseen that Armagh, Dungannon and Portora would find themselves in a distinct political jurisdiction from Cavan and Raphoe. Yet the very survival of all five is testimony to the enduring impact of the Ulster Plantation on Irish society. HI

Kenneth Milne is chairman of the Christ Church Cathedral Culture Committee.

Richard Bartlett’s map of Armagh c. 1600. In 1610 the Royal School moved from Mountnorris to the site of the ruined former Columban abbey (top right-hand corner), where it remained for over a century. (National Library of Ireland)

Further reading:

The 1608 Royal Schools celebrate 400 years of history, 1608–2008 (Aghalee, 2007).