‘Rebell privy counsellors’: the first Catholic confederate supreme council, July 1642

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2015), Volume 23What was the composition of the first supreme council elected in June 1642 prior to the first formal meeting of the Association of Confederate Catholics of Ireland the following October, a list that until now has remained elusive?

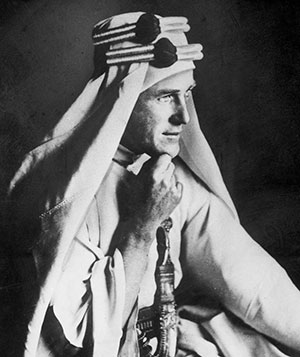

Portrait of David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, a member of the first supreme council, by an unknown artist, 1644. (Private collection)

The outbreak of rebellion in Ulster in October 1641 initiated a period of political turmoil that spread rapidly throughout the island. Government inability to achieve a decisive victory over insurgents and a mass exodus of Protestants left a major swath of territory in rebel hands. Lower orders took full advantage of the ensuing chaos and many aggrieved gentry also joined the insurgents. As unrest continued, some concerned Catholic magnates, realising the need for accommodation with the Crown, gradually assumed political control. Under their supervision, insurgents began to coalesce by late 1641. Thereafter, the widespread distribution of an oath of association instigated moves towards alternative government in rebel quarters. Clerical endeavours in the oath’s circulation alongside their proposal to create a joint lay–clerical council at the Synod of Kells in March 1642 guaranteed them a leading role in the resultant administration. Two months later, their national congregation declared the insurrection ‘lawful and just’ and repeated calls for a ‘general council’ to coordinate the war effort. In June an assembly of lords, clergy and commons at Kilkenny established a supreme council of ‘a few choice hands . . . to gather all the springs into one channell’. According to Micheál Ó Siochrú, this first council sat from 11 June to 15 July. There is no evidence that another was elected prior to the general assembly of late October 1642.

Because of the sparse nature of the evidence, historians have long overlooked these early assemblies. Nevertheless, employing the eyewitness testimony of Richard Bellings, the Kells congregation decrees and June assembly records, Cregan determined that the first council consisted of twelve members drawn from the nobility, clergy and major towns, with three representatives from each province. He further argued that it comprised a general, a bishop, a temporal lord and eight gentlemen, one of whom was a ‘professor of the law’, and concluded that these eleven figures, accompanied by Viscount Gormanston (designated president in the assembly records), constituted the twelve. Bellings, however, named Viscount Mountgarret as president and also identified Heber MacMahon, bishop-elect of Down and Connor, as a councillor. Therefore the only conclusion to be drawn from the official sources was that the council was envisaged as a twelve-strong body with the aforementioned three figures afforded seats. Because its remaining members were not revealed, it was believed that a definitive list no longer survived.

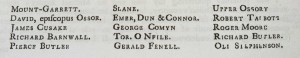

The fifteen ‘noblemen and gentlemen’ elected ‘by the lords and commons of three provinces’ who signed a letter to the marquis of Clanricarde on 11 June 1642. (U. de Burgh, The memoirs and letters of Ulick, marquis of Clanricarde . . .)

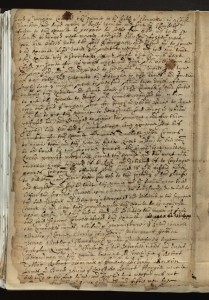

One source hitherto neglected in the search for the elusive council membership is the 1641 Depositions. These accounts, taken from Protestant refugees and former confederates in the 1640s and ’50s, have experienced a chequered reputation in Irish historiography. Once dismissed as credible sources, nowadays they are acknowledged as the only available evidence for reconstructing the rebellion’s early months. Among the testimonies collected for County Wexford there are separate reports by Donatus Connor and Henry Masterson, local Protestants imprisoned and put on trial before the supreme council at Kilkenny in July 1642. Significantly, after their liberation they reported the councillors’ names to the Dublin government. Aware of the treasonous nature of the alternative government in Kilkenny, Masterson and Connor were only too eager to expose the confederate political hierarchy.

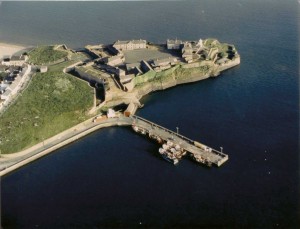

The deposition of Henry Masterson, who fled Moniseed, Co. Wexford, for the government garrison at Duncannon Fort (above) in late October 1641. (Trinity College, Dublin)

According to Donatus Connor’s testimony, his home at Artramen was attacked around 7 November 1641. As a Protestant minister he was a primary target for insurgents and sought protection in Wexford town. He survived there until March 1642, when the town’s remaining Protestants were expelled. Connor had previously been a Catholic priest and the insurgents were anxious to rid themselves of such a prominent apostate. He was duly imprisoned in ‘a most odious dark and lothsome dungeon’ and remained there until summoned to Kilkenny by a warrant from Mountgarret, Gormanston ‘and other of the Rebellious Counsell’. By contrast, Henry Masterson fled Moniseed for the government garrison of Duncannon in late October 1641. He was afterwards employed by Lord Esmonde, fort governor, to deliver letters to Lord Justice William Parsons at Dublin. His mission fulfilled, Masterson returned home but was apprehended and was subsequently incarcerated in the same dungeon as Connor and two further co-religionists, his father, Roger Masterson, and Francis Talbot. Although he escaped this initial custody, Masterson was again captured and placed in ‘bolts of iron’ at Sir Morgan Kavanagh’s castle at Clonmullen, where only the intercession of servants saved him from immediate hanging. Kavanagh was subsequently frustrated in securing a warrant to execute Masterson as a ‘herriticke’, and the prisoner remained in irons ‘untill such tyme as the bolts did eate into his fleashe to the bones’.

Ultimately, each detainee was sent to be ‘tried for his lyfe before their supreame councell’. All four were transported to Kilkenny, the confederate capital, charged with failure either to convert to Catholicism or to leave insurgent quarters and with conspiring against the confederates. Connor withstood constant attempts to reconvert before facing allegations of clandestine correspondence with his father in England during custody. The Mastersons were likewise interrogated about intercepted dispatches from Lord Esmonde to Sir William Parsons. After consultation, it was decided that the group posed little risk and they were freed. Connor reached Dublin before 13 October 1642, where he recorded the first of two depositions. Henry Masterson gave his first report on 8 January 1643 and three further testimonies at later dates. Their information, corroborated by independent depositions, makes it possible to date the trial. Connor reported being sent to Kilkenny ‘about the first of July’, while a separate examination given on 29 July claimed that the group were transferred there ‘about three weekes since’. This approximates their case to early July 1642, thereby proving its hearing before the first supreme council.

Letter to the marquis of Clanricarde

In their depositions, both former detainees provide fragmented lists of the councillors they encountered. Masterson’s reports provide ten names while Connor lists nine. Five are common to both (Viscounts Mountgarret and Gormanston, Piers Butler, David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, and Heber MacMahon, bishop-elect of Down and Connor), giving a total of fourteen councillors. Therefore, rather than the planned council of twelve, the numbers were higher, perhaps 24 as on the five subsequent councils to 1645. But with only fourteen names from the deponents, how can the remaining ten be found? An instructive source is a letter to the marquis of Clanricarde by fifteen ‘noblemen and gentlemen’ elected ‘by the lords and commons of three provinces’. Dated 11 June 1642, this can only be a section of the supreme council, a fact underlined by the signatures of eight of those named in the Connor–Masterson depositions. Providing seven new names, this source increases the membership to 21, leaving three undisclosed councillors. Their identification lies among the ‘divers clergy men’ who both deponents claim made up the numbers. Masterson could not identify them but Connor conveniently provides the names of Frs Nicholas French, Richard Synnot and Nicholas Shee. That these priests were actually a clerical committee attending the trial cannot be discounted, but Connor did describe Synnot as a ‘rebell privy counsellor’.

In their depositions, both former detainees provide fragmented lists of the councillors they encountered. Masterson’s reports provide ten names while Connor lists nine. Five are common to both (Viscounts Mountgarret and Gormanston, Piers Butler, David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, and Heber MacMahon, bishop-elect of Down and Connor), giving a total of fourteen councillors. Therefore, rather than the planned council of twelve, the numbers were higher, perhaps 24 as on the five subsequent councils to 1645. But with only fourteen names from the deponents, how can the remaining ten be found? An instructive source is a letter to the marquis of Clanricarde by fifteen ‘noblemen and gentlemen’ elected ‘by the lords and commons of three provinces’. Dated 11 June 1642, this can only be a section of the supreme council, a fact underlined by the signatures of eight of those named in the Connor–Masterson depositions. Providing seven new names, this source increases the membership to 21, leaving three undisclosed councillors. Their identification lies among the ‘divers clergy men’ who both deponents claim made up the numbers. Masterson could not identify them but Connor conveniently provides the names of Frs Nicholas French, Richard Synnot and Nicholas Shee. That these priests were actually a clerical committee attending the trial cannot be discounted, but Connor did describe Synnot as a ‘rebell privy counsellor’.

The breakdown of authority made the early assemblies unrepresentative of the wider Catholic community. No Connacht delegates attended and there were only four Munster representatives, while Bishop-elect MacMahon and Turlough O’Neill, brother of Sir Phelim O’Neill, were the sole Ulster deputies. The remainder were Leinstermen, proving that representation was heavily weighted in favour of the eastern province. Furthermore, with four councillors from the Butler family, it is clear that local interests also predominated, emphasised by the appointment of David Rothe, bishop of Ossory, to the council.

Participation in later councils

Of the 24 members, twelve sat on future councils. MacMahon, transferred to Clogher in 1643, was the only figure to sit on every council in the 1640s. Richard Bellings was secretary on seven further occasions, while George Comyn was an ever-present until 1645. The peers had contrasting futures on the council. Mountgarret and Netterville played leading roles until 1645–6, while the untimely deaths of Slane and Gormanston in late 1642 and mid-1643 respectively eradicated the Pale nobility’s representation. Although Barnaby Fitzpatrick, baron of Upper Ossory, was active in the early revolt and helped present the confederate remonstrance at Trim in March 1643, he played only a negligible role thereafter. Others, like James Cusack, former attorney of the Commission for Defective Titles, and Sir Richard Barnwell, had acted as Catholic party leaders in parliament. Their presence reveals the transformation of the Catholic struggle from reactionary politics to revolutionary government. Cusack was elected to the second supreme council in October 1642 but was afterwards redeployed as attorney general and judge of the admiralty. Likewise, Barnwell was employed as a peace commissioner, only returning to the council in 1647 as a supernumerary. Gerald Fennell, a physician, sat on a further five councils and became a leading member of the peace faction. Some were re-elected as councillors later in the decade: Piers Butler in 1646–7 when the clerical party came to dominance, and Robert Talbot, after serving as an army commissioner and on various negotiating committees, as a supernumerary in 1647.

Alternatively, some of the original councillors never again served on the executive. Bishop Rothe played only a passive role in politics afterwards, while Sir Edward Butler remained inactive until raised to the peerage as Viscount Galmoy in 1646. Others reconcentrated their efforts towards ancillary affairs. Rory O’Moore, one of the original conspirators of the rebellion, acted as interim general of the forces of upper Leinster and pursued a mainly military career. Of the possible clerical councillors, only Nicholas French, elected bishop of Ferns in 1645, operated on the council again. Richard Synnot retreated from secular politics to concentrate on administrative duties with the Franciscan order, while Fr Nicholas Shee acted as a diplomatic envoy in Flanders. Philip Hore of Kilsallaghan, treasurer of the insurgent forces in County Dublin, was later appointed as commissioner of the Leinster army. Only two councillors, the lawyer Christopher Nugent, possibly a brother of the earl of Westmeath, and Oliver Stephenson, a cavalry officer in the Munster army, seem to have played no further part in confederate politics.

Despite speculation that the first council was a twelve-strong body designed to represent all provincial interests, what emerges from these sources is an executive of 24, staffed mainly by Leinster and local interests, substantiating Bellings’s claim that their election had ‘much of chance and little of premeditation’. Some retained their positions on later councils while others departed from high politics once the confederation became more fully representative of Catholic Ireland. In truth, the first supreme council was an emerging administration manned by an eclectic mix of bishops and nobles, soldiers and lawyers, priests and parliamentarians, who together constituted the pioneers of Catholic government and the ‘rebel privy councillors’ of the confederate counter-state.

Jason McHugh is a former IRCHSS and An Foras Feasa post-doctoral fellow.

Read More: Membership of the first confederate supreme council, June–July 1642

Unanswered questions

Further reading

D. Cregan, ‘The Confederate Catholics of Ireland: the personnel of the Confederation, 1642–9’, Irish Historical Studies 29 (1995).

U. de Burgh, The memoirs and letters of Ulick, marquis of Clanricarde, and earl of Saint Albans: lord lieutenant of Ireland . . . (London, 1757).

http://www.1641.tcd.ie/, Depositions of Donatus Connor and Henry Masterson.

M. Ó Siochrú, Confederate Ireland, 1642–1649: a constitutional and political analysis (Dublin, 1999).