Narcissus Marsh & his library

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1996), Volume 4

Portrait of Archbishop Marsh, attributed to Hugh Howard.(Courtesy of March’s Library)

It is curious that the career and achievements of Archbishop Narcissus Marsh (1638-1715) have received little attention from modern historians. One explanation may be the dismissive views of William King (1650-1729), the powerful Archbishop of Dublin, who said Marsh was ‘very dextrous at doing nothing’ or even more likely Jonathan Swift’s spiteful ‘Character of Primate Marsh’ written about 1710:

He is the first of human race, that with great advantages of learning, piety, and station ever escaped being a great man… No man will be either glad or sorry at his death, except his successor.

Avoided marriage

Narcissus Marsh was born in 1638 in a village called Hannington in Wiltshire. He said in his diary that he was ‘of honest parents’. His brothers Epaphroditus and Onesiphorus were also given names from St Paul’s Epistles. At Oxford he decided to become a priest. He was offered the living at Swindon and was ordained by Dr Skinner, Bishop of Oxford, although he was under age for ordination. After some difficulties Marsh took up residence in Swindon, and then discovered to his horror that in return for his appointment he was expected to marry a friend of the persons responsible for his preferment. Marsh refused. He wrote in his diary that he had no intention of ever getting married, but on this occasion he offered the reason that his father was opposed to the marriage and he had no wish to disobey him. Marsh thanked God for delivering him ‘out of the snare which had been laid for him’ believing that he would not be able to serve God and the Church properly if he was married. It seems that Narcissus Marsh was a handsome man and had many difficulties escaping from matrimony. He writes many amusing accounts of his narrow escapes. He said he had many ‘advantageous offers’ which included substantial dowries. One lady had £800, another £500 and another £2,400 and he noted, they were ‘very desirable, beautiful, lovely persons’.

Marsh returned to Oxford and continued his studies there. His studies included ‘old philosophy, mathematics and oriental languages’. He published a book on logic and later an essay on music; he played the bass viol. Marsh was not entirely happy about this pastime, saying: ‘Oh Lord, I beseech thee to forgive me this loss of time and vain conversation’. Marsh was appointed Principal of St Alban Hall in Oxford by the Duke of Ormond who was Chancellor of the University. He made a great success of this position and it was no doubt his administrative and organisational ability which encouraged the Bishop of Oxford, Dr Fell, and the Duke of Ormond to suggest a more important appointment for Narcissus Marsh, the Provostship of Trinity College in Dublin which he took up in 1679.

‘The cages’ at the end of second gallery. Originally readers were locked in for security reasons.

(Courtesy of Marsh’s Library)

‘Lewd and debauch’d town’

But Marsh seems to have been unhappy in Trinity, complaining that he was

finding this place very troublesome partly by reason of the multitude of business and impertinent visits the Provost is obliged to, and partly by reason of the ill-education that the young scholars have before they come to the college whereby they are both rude and ignorant; I was quickly weary of 340 young men and boys in this lewd and debauch’d town; and the more so because I had no time to follow my always dearly beloved studies.

This constant complaint continues throughout Marsh’s diary. He was basically a scholar who disliked ‘worldly business’. Yet he was also a very practical man and realised that the buildings and facilities for students and staff in the college were inadequate. He began by building a new college hall and chapel and he also developed the library. He checked and revised the library regulations, and insisted that when the new library keeper was appointed all the books in his care must be accounted for and that the old library keeper replace the missing books or pay for them.

Promoter of the Irish language

At Trinity Marsh revived the project to publish an Irish translation of the Old Testament. Bishop Bedell had supervised the translation of the Old Testament into Irish before 1641 but it had never been printed. Marsh with a team of assistants prepared the transcripts which they then sent to the Hon. Robert Boyle in London. The Irish translation of the Old Testament appeared there in 1685. Marsh was not content with this achievement. He discovered that under the statutes of the college thirty of the seventy scholars chosen each year had to be natives of Ireland. Marsh noticed that while these thirty scholars could speak Irish they could not read or write it. He was determined to rectify this situation and he employed, at his own expense, a former Catholic priest, Paul Higgins, to teach Irish to the students and to preach an Irish sermon once a month. The sermons and lectures were very popular. The attendance was never less than 300 at the sermons and eighty students came to the lectures. Marsh as Provost himself set a fine example by attending both lectures and sermons. He was severely criticised both by the Lord Primate and by many important people in the government for promoting the Irish language. He was told that there was an Act of Parliament the object of which was to abolish the Irish language. Marsh ignored their warnings and continued with his work. While he was undoubtedly interested and enthusiastic about the Irish language for its own sake (he had a scholar’s interest in languages), his main purpose was to communicate with the majority of the Irish people in order to propagate the reformed religion.

Marsh was one of the first members of the Dublin Philosophical Society. He contributed an early paper to that Society, ‘An Introductory Essay on the Doctrine of Sounds, Containing some Proposals for the Improvement of Acoustics’. The paper was remarkable because of Marsh’s use of three new words. He used DIACOUSTICS to describe the study of refracted sound, CATACOUSTICS for that of reflected sound, and most important of all, he was the first scientist to use the word MICROPHONE.

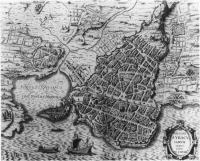

Map of Syracuse from Sicilia antiqua by Philippus Cluverius(1580-1622) – Dr Bouhereau Collection.

‘Sad and calamitous times’

Marsh’s next appointment was to the bishopric of Ferns and Leighlin in 1683. He took up residence in his diocese but he did not stay for long. King James was on the throne, and these were difficult days for a Protestant bishop in the Irish countryside. Marsh was subjected to various threats and spent many days in hard study, ‘especially in knotty algebra to divert melancholy thoughts these sad and calamitous times wherein I am forced to live far from home’. Marsh returned to Dublin and stayed in the Provost’s house and a short time later left for England. He returned to Ireland after the battle of the Boyne and resumed his duties. In 1690 Marsh became Archbishop of Cashel and four years later was promoted to the archdiocese of Dublin. He undertook his new duties with diligence and never spared himself visiting his clergy throughout his large diocese.

Marsh now became even more influential gaining membership of the Privy Council and being appointed Lord Justice seven times. His diary for this period gives an insight into his character and some of the historic events that occurred in Ireland. Apart from the amusing and detailed accounts of his dreams Marsh records his attendance in the House of Lords, and his appointment to several committees. He also refers several times (1692-95) to the famous Toleration Bill and the clauses regarding the inclusion of the sacramental test to ‘be imposed as it is in England and that persons obliged to take it likewise receive the communion thrice in the year at least’. He later refers to the bill for ‘encouraging Protestant strangers’ and the bill for ‘abrogating popish holydays’.

The Penal laws

Marsh was involved in drafting the Penal laws but he was by no means the only originator of these acts. Marsh’s support of penal legislation against Catholics and his animosity towards Dissenters could possibly be explained by some entries in his diary. He was obviously terrified of the Pope and the possibility of Catholics gaining power or influence in Ireland. Archbishop King said in his sermon at Marsh’s funeral that ‘though a strict and rigid adherer to the service of our church, yet so far as I could observe neither Dissenters nor Roman Catholics did ever complain of him: on the contrary they looked on him as a mild and merciful adversary that rather chose to convert than hurt them’.

It is also clear that Marsh was not prepared to carry out persecutions without government support, for example in the case of an action against Mr Fleming, a Presbyterian minister in Drogheda, which was withdrawn. His approach to the Huguenots, who had been encouraged to come to Ireland by the government, was quite different. With the Huguenots he showed great skill and understanding. At that time they worshipped in the Lady Chapel of St Patrick’s Cathedral and they were bound by the discipline and canons of the Church of Ireland under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Dublin. The French congregation prepared its own discipline, a more liberal interpretation of conformity than that required of them as a condition of their use of the Lady Chapel. They submitted it to the Archbishop who approved it. Marsh has been praised for his moderation in this case but it was a very shrewd move: the Huguenots gradually merged into the Church of Ireland.

Archbishop Marsh was made Primate in January 1703. He was now sixty-five years old. Even so, he continued with his work for his church. He repaired the cathedral in Armagh, rebuilt many churches in the archdiocese at his own expense, and he contributed large sums of money to the missionaries in the Indies. That was not all. He instituted, and largely endowed, the almshouses in Drogheda for the widows of clergymen, and provided them with pensions. Primate Narcissus Marsh died on the 2 November 1713 and was buried in St Patrick’s churchyard beside his beloved library which is his crowning achievement and lasting monument.

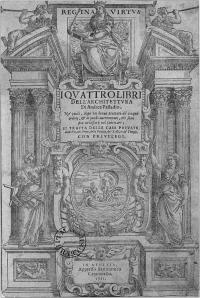

Title page of I quattro libri dell’architettura by Andrea Palladio (1508-80) – Archbishop Smyth Bequest

Marsh’s Library

While Provost of Trinity College Marsh observed how difficult it was to use the library there:

But that which renders the library almost useless to all, but some of the College, is this, that by the College statutes no man, besides the Provost and Fellows is permitted to study there, unless carry’d up thither by one of them, who is bound to be present all the time the other stays in the library: and ‘twas this, and this consideration alone that at first mov’d me to think of building a library in some other place (than in the college) for public use, where all might have free access, seeing they cannot have it in the College; nor are our booksellers’ shops furnished anything tolerably with other books than new trifles and pamphlets, and not well with them also.

When Marsh built his library and provided the books he was anxious to have it and its government incorporated in an Act of Parliament. He drew up ‘An Act for Settling and Preserving a Public Library forever. Unfortunately the Bill met with great opposition. This opposition came from some of the bishops and clergy who were meeting in Convocation. Convocation was the Synod of the clergy which met at the same time as Parliament to discuss legislation affecting the Church. And it was while Convocation was meeting and Marsh’s Bill (already passed by the English Privy Council) was still pending in the Irish House of Lords that the clergy in the lower House of Convocation opposed it.

Clerical opposition

One of the leaders of the opposition was Jonathan Swift who had been elected as Proctor to represent St Patrick’s Cathedral in the lower House of Convocation. There were two reasons for the opposition to Marsh’s Bill. The principal objection was because Marsh wished to annex the office of Keeper of the Library to the ecclesiastical office of Precentor of St Patrick’s Cathedral. Thus, since ecclesiastical titles and ancient benefices were attached to the Cathedral offices, the opposition claimed that this proposal to annex the librarian’s job to the precentorship of St Patrick’s could mean that church property might be lost to the Establishment and laymen on the board of the library might have authority over the Precentor. Another reason for the clergy’s objections was Marsh’s proposal that the Huguenot refugee, Dr Elias Bouhéreau, would be appointed Keeper. One of the grounds for his appointment was that he would donate his collection of books to the library. Because of this requirement the opposition could claim that Bouhéreau’s gift involved simony through the sale of an ecclesiastical office. It could also be claimed that because the office of Precentor belonged to the Cathedral Bouhéreau’s appointment infringed on the power of the Dean and Chapter of St Patrick’s Cathedral. Swift agreed with the clergy that Marsh’s Library Bill was dangerous and that it contained simony and sacrilege. His opposition arose from a genuine belief that in this instance it was necessary to preserve the rights of the lower clergy against the bishops and laymen.

In spite of these violent debates and Swift’s opposition, the Bill incorporating the Library as a public library forever was eventually passed in 1707. The attempt to unite the Treasurership or Precentorship of St Patrick’s Cathedral to the office of Librarian had been dropped after objections from Archbishop King. All this greatly distressed Marsh. He wrote to his friend Dr Smith in Oxford describing the opposition:

By this you will perceive how difficult a matter it is for a man to do any kindness to the people of this country. If he be a public benefactor, he must resolve to fight his way through all opposition of it; it being a new and unheard-of thing here… But the opposition continued to the last, not levelled against me directly, or my design in it, but that the Bill contained in it simony, sacrilege and perjury.

Design

The Library was designed by Sir William Robinson. It was beautifully arranged and I strongly believe that Archbishop Marsh must have given very strict instructions to his architect. It cost Marsh £5,000 and he intended spending another £500 on it. At Oxford he had became familiar with the design and the organisation of the Bodleian Library. He had an interleaved copy of its printed catalogue which he carefully annotated. When Marsh was in Oxford the Bodleian Library was in its heyday and was regarded as one of the most famous and important libraries in Europe. Indeed in his correspondence Marsh specifically refers to the Bodleian Library when he was discussing the design of his own library. He wrote to his friend, Dr Thomas Smith, concerning the upper part ‘that is contrived like the cross part of the Bodleyan Library’.

The Library is now one of the few eighteenth-century buildings left in Dublin which is still being used for its original purpose. The books are housed on the upper storey while the Librarian resides in the lower – thus absorbing the building’s damp! The Library is furnished with magnificent dark oak bookcases each with a carved and lettered gable topped by a mitre.

The first gallery is sixty feet long and the second gallery is seventy-six feet long, at the end of which are three wired alcoves usually called ‘the cages’. These were intended by Marsh for the protection of the smaller more valuable books. Another protective measure was the use of chains on the lower shelves of the bookcases throughout. But even the use of chains in Marsh’s is a bit different. In earlier chained libraries the foredge or the front part of the book faced outwards while in the case of Marsh’s the spine faced outwards. These chains were removed in the middle of the eighteenth century.

From Latium by Athanasius Kircher SJ(1602-80)-

Bishop Stillingfleet Collection.

The collections

In 1705 Marsh purchased the library of the late Bishop Edward Stillingfleet (d.1699) containing nearly 10,000 books for just over £2,000. The Stillingfleet collection, the most important in the Library, was acquired very soon after the building was erected. Bishop Edward Stillingfleet had been Dean of St Paul’s and later Bishop of Worcester. He was one of the best known preachers and writers of his day. His library was regarded as the best private library in England. There was consternation at the proposed sale, and many attempts were made to find an English buyer; even King William was approached. But Marsh was successful and the Stillingfleet collection was brought to Dublin and placed in the first gallery by Archbishop Marsh and the first Librarian Dr Bouhéreau in 1705. It contains books on a wide range of subjects including theology, history, the classics, law, medicine and travel.

Dr Bouhéreau left his books to Marsh’s when he was made Librarian in 1701. This collection relates to France and to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the religious controversies of the seventeenth century. It contains books on medicine which was Bouhéreau’s profession in La Rochelle. Marsh donated his own books and the fourth major collection was bequeathed in 1745 by John Stearne, the Bishop of Clogher. Stearne is the only major Irish collector in the Library and a considerable part of his collection relates to Ireland. But there are also some very important books of Irish interest in both Marsh’s and Stillingfleet’s collections. Marsh also showed great interest in Irish manuscripts. Earlier, in 1695, Marsh had purchased the manuscripts belonging to the Dublin orientalist, Dudley Loftus. Many of these relate to Irish history. They include O’Hussey’s Grammaticæ Hibernicæ Rudimenta, an Irish-Latin dictionary (1662), Royal grants in Ireland 1604-31, and Thady O’Doyne’s letters and surrenders 1559, 1590 and 1606.

Archbishop Marsh’s interest in Irish books and manuscripts was maintained by the Librarians of the early part of this century. From the small annual book-purchasing fund of £20 (never increased) they managed to buy a collection of books and periodicals relating to Irish history printed within the last hundred years. The Library also received the Dean Webster Donation in 1941, a collection of manuscript material relating to Irish antiquities, deeds relating to County Cork and notebooks belonging to Bishop William Reeves.

There are 25,000 books in Marsh’s. There are eighty incunabula, that is books printed before 1501. There are 430 books printed in Italy before 1600. There are 1,200 books printed in England before 1640, and there are 5,000 books printed in England before 1700. Because the books were collected at the same time they make a homogenous collection. The collectors in Marsh’s were interested in similar subjects, although Marsh’s own library is slightly different because it illustrates his interest in oriental material including Arabic and Hebrew books

It is easy to forget that in the early eighteenth century Marsh’s would have been regarded as a modern library with the latest books and a modern classification system. To study and examine the books in Marsh’s is to explore a world which has been one of the hallmarks of Europe’s great cultural heritage. Marsh’s has been used by scholars for nearly three hundred years. It was always intended to be a working library and it continues to be so, but it is not used by scholars as often as it should be. This is probably due to the fact that we do not have a printed catalogue of all the books in the Library. We do have printed sectional catalogues—manuscripts (1913), French books (1918), English books to 1640 (1905) and music books and manuscripts (1982)—but these are now out of print. However, a new and exciting project has just begun: the catalogue of the entire collection is being computerised. Eventually it will be accessible to readers through the Internet which will open the Library to international scholarship. Marsh’s can then become a major centre for seventeenth-century studies.

Muriel McCarthy is the Librarian of Marsh’s Library.

Further reading:

M. McCarthy, All graduates and gentlemen: Marsh’s Library (Dublin 1980).

M. McCarthy, ‘Swift and Marsh’s Library’ in Dublin Historical Record, vol. XXVII, no.3, June 1974.

R. Mant, History of the Church of Ireland. Vol.2 (London 1840).

G.T. Stokes, Some worthies of the Irish Church (London 1900).