At Ó Néill’s right hand: Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire and the Red Hand of Ulster

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2010), Volume 18

A literal (and slightly disturbing!) depiction of the origin of the Red Hand of Ulster image in a loyalist mural off Belfast’s Lower Shankill Road. Coats of arms often pun by alluding to the name of the family concerned, known as ‘the canting of arms’, and the use of distinctive Gaelic features is well represented by the heraldic emblem of the Uí Néill. According to tradition, Heremon, the third son of Milesius and first Uí Néill king of Ireland, resolved a dispute with a rival king by staging a boat race in which the winner would be the one who touched dry land first. When his opponent built up a lead, Heremon had to act fast. He drew his sword, cut off his right hand and threw it onto the shore, thereby establishing the royal line of Uí Néill descendants who ruled over large parts of Ireland for centuries. This imagery would not have been lost on Ó Maolchonaire, whose own family were hereditary genealogists and chroniclers. O’Farrell’s Linea Antigua genealogy states that Ó Maolchonaire’s family were amongst the ‘kings, nobility and gentry of Leinster, Conaght, Ulster Scotland &c. descended from Heremon, third son of Milesius of Spain’.

As the loyalist murals of Belfast’s Shankill Road and the jerseys worn by Tyrone’s Gaelic footballers show, claims to the Red Hand of Ulster have been contested for centuries. From the earliest times, personal emblems have been used to identify prominent people and their descendants. The lasting use of such symbols extended to civil purposes to authenticate documents and indicate the ownership of property. In the feudal system, society was held together by personal allegiance. Members of the aristocracy who nominated clergymen for higher office required from them an act of homage. An Irish echo of this practice occurred in the early seventeenth century. After his nomination by Aodh Ó Néill, the newly appointed Catholic archbishop of Tuam, Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire, took for his coat of arms the Red Hand of Ó Néill.

Claimed descent from the southern Uí Néill

Measuring approximately 25mm or one inch across, the wax impression of Ó’Maolchonaire’s seal has survived intact on only a handful of documents recently discovered at the Archivo General de Simancas and at University College Dublin. His use of the Red Hand seems a curious choice, considering his family background in Roscommon and his role as archbishop of Tuam. The see of Tuam was created by St Jarlath in the sixth century and raised to an archbishopric at the synod of Kells in March 1152. As was the case with other Irish episcopal seals, that of Tuam usually included an image of the patron saint of the diocese. Prelates could, however, vary their coats of arms and, on closer examination, the Red Hand was well chosen by Ó Maolchonaire for his purposes. The Uí Néill shared with the kings of Connacht a traditional descent from Conn of the Hundred Battles. In the late tenth century, Domhnall Ó Néill assumed the title and surname Ó Néill for the ruling dynasty of the Connachta from his grandfather Niall Glúndubh (‘Niall of the black knee’), to whom the conquest of most of Ulster is attributed. The Uí Mhaolchonaire, on the other hand, did not claim Connacht descent but traced themselves back to a branch of the southern Uí Néill from present-day Westmeath. This may explain Ó Maolchonaire’s decision to use the Red Hand but, since this symbol is normally associated with Ulster, its use also reveals his deep political involvement with the earls of Tyrone. The authority of Ó Maolchonaire’s traditional patrons in Connacht had waned by the late 1500s and he came to prominence as confessor to Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill (Red Hugh O’Donnell) at the height of the Nine Years’ War, remaining loyal in his service to the Gaelic chiefs of Ulster throughout his career. He served as interpreter and adviser to the Ulster earls during their stay in Spanish Flanders and became Aodh Ó Néill’s closest political ally after the demise of Rudhraighe Ó Domhnaill.

Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire’s appointment to the archbishopric of Tuam in 1609 coincided with the beginning of the Ulster Plantation. As Aodh Ó Néill had received no direct response to the letters he had written to Philip III since December 1607 and the Spanish council of state would not allow him to approach the king of Spain in person, the earl of Tyrone sent Ó Maolchonaire to the court of Philip III as his representative. Madrid was a focal point of politics and commerce in early seventeenth-century Europe. Envoys from Portugal, the Italian and German states, Flanders and Brabant, England and Scotland all congregated in the Spanish capital. By asserting his hereditary claims to Ulster, Ó Néill hoped to convince Philip III of Spain to grant him a swift return to Ireland at the head of an army. The new archbishop’s task on the earl’s behalf became all the more urgent when they learned of plans to ‘declare confiscated up to six counties of the lands belonging to the earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell’. Ó Maolchonaire wrote to the Spanish council of state, stating that James I was ‘offering the said lands perpetually to all the English and Scots and their heirs who wish to inhabit them, provided that they pay a certain amount to the king every year’. Referring to the proposals published that year, Ó Maolchonaire said that the lands were to be granted on condition that ‘they must swear that the king is head of the Church […] they cannot rent the said lands to any Irishman of the ancient lineage of Ireland’.

The ‘shorthand of history’

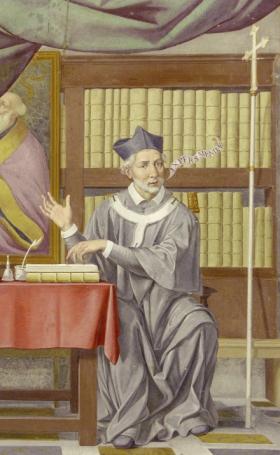

Fresco of archbishop of Tuam Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire OFM, painted by Fra Emanuele da Como, Aula Maxima, St Isidore’s College, Rome. (Gioberti Studio)

While Ireland’s annals chronicled the deeds of each ancestral lineage, heraldry enabled eminent families to avail of a method of commemoration termed the ‘shorthand of history’. Regrettably few Irish matrices or their impressions remain to us. Sealing wax introduced in the seventeenth century was easily broken and, to prevent counterfeit use being made of the matrix after the death of the original owner, the moulds were frequently effaced and destroyed. As a consequence, little has been written from an Irish perspective on sigillography, that is, the reading, dating and interpretation of seals.

Heraldry emerged as ‘a science and an art’ between 1135 and 1155 with the development of visors and full armour, when combatants had to clearly distinguish themselves. In their military aspect, arms became a mark of identity and of social status. Evidence exists for the use of seals on documents in Ireland following the Norman invasion, with Gaelic lords adopting the same system of heraldry by the fourteenth century. Gaelic arms preserved on extant seal matrices and the impressions they made on documents provide us with much of the information available on the subject of medieval Gaelic armory. The earliest extant Gaelic seal is attached to the treaty agreed between Rudhraighe Ó Cinnéide and the earl of Ormond in 1356. Use of heraldry by the Mac Murchadha Caomhánach dynasty in Leinster suggests their recognition of inheritance by primogeniture. Murchadha Mac Murchadha Caomhánach, for instance, used the arms of his grandfather Domhnall Riabhach in 1515.

To assert their claims to the kingship of Ulster during the fourteenth century, successive chiefs of the ruling branch of the Uí Néill used the title Rex Ultonie and the Red Hand device while associating themselves with Conchobhar mac Nessa, the sagas of Eamhain Macha and the warriors of Ulaidh. After its use on the seal of Aodh Reamhar Ó Néill, king of the Irish of Ulster, who died in 1364, the Red Hand became ‘a permanent feature of their memorial bearings and their dependent chieftains’.

Ownership repeatedly disputed

Recognition of the status bestowed by the Red Hand badge was not exclusive to Ulster, as demonstrated by the legendary late fourteenth-century Mac Murchadha chief Diarmait Láimhdhearg. Ownership of the Red Hand and its powerful imagery was repeatedly disputed. A fifteenth-century poem addressed to Art Mac Aodha mhic Airt Mhéig Aonghusa, chief of Uibh Eathach in present-day County Down, claimed that the Uibh Eathach and their ancestors the Ulaidh were the true warriors of the Red Hand, ‘the shedders of blood, that is, since they had repeatedly slaughtered the men of the rest of Ireland’ without ever being required to pay compensation. This challenge arose again about 1680.

Despite saying that he had seen no heraldic device ‘for a Milesian Irish family’ anterior to the reign of Elizabeth I, John O’Donovan declared that many Gaelic families preserved ‘those simple badges which their ancestors had on their standards’, such as the Red Hand of Ó Néill. This reflected the strong sense of perpetuity felt by Irish exiles in the early seventeenth century while also appealing to the deep pride shown by the Spanish in their ancestry and family connections. According to the account of Irish origins in the late eleventh-century Leabhar Gabhála, three sons of the Spanish king Milesius—Heremon, Heber and Ith—came to Ireland from northern Spain about the time of Alexander the Great. They conquered the land and, henceforth, every Gaelic royal pedigree traced its descent from the Milesians.

Practical purposes

Ó Maolchonaire’s crest: the Red Hand, surrounded by a flowing material known as mantling, appears below a flat, wide-brimmed episcopal hat, flanked by rows of tassels on each side. The archbishop’s cross appears between the hat and the Red Hand, denoting his metropolitan jurisdiction as primate of Connacht. Although only the beginning and end of the inscription (top right and top left respectively) are visible in this particular reproduction, the edge of the seal is inscribed with Ó Maolchonaire’s name and title in Latin: Florentius Conrius Archiepiscopus Tuamensis. (Archivo General de Simancas)

Seals served practical purposes, guaranteeing the security and the authenticity of a text and undersigning its objective. In cases where contracting parties were unable to subscribe their names to important documents, sigillography provided a mark of attestation. Prelates could impale together their personal and official arms by dividing the shield down the middle and placing arms in both halves, or quarter them by dividing the shield in four or more, with the most important arms in the top left-hand corner. In contrast, the clear legibility of Ó Maolchonaire’s seal, free from the numerous symbols associated with heraldry, avoided confusion and made it instantly recognisable.

Dextra Dei

A symbol of spiritual authority, the hand in heraldry is a sign of faith, sincerity and justice. The Red Hand of Ó Néill can therefore be explained as Dextra Dei, the ‘hand of God’. In early Christian iconography, God the Father was frequently represented by the open right hand, sometimes within a halo or nimbus. This image is preserved under the arm and ring on the north side of the tenth-century high cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice, Co. Louth. The arm, such as that of the Ó Domhnaill of Tír Chonaill, signifies diligence and steadfastness, while an arm covered with armour—that of Cathail Croibhdhearg, king of Connacht, for instance—refers to one prepared for ‘performances of high enterprise’.

At a time when feats of arms were essential to maintaining political influence, the Uí Néill took on the war-cry of Lámh Dearg Abú!—‘Up with the Red Hand!’ The historian Cox called the Red Hand of Ó Néill ‘that terrible cognizance’, while the sixteenth-century English writer Edmund Spenser observed that, in joining battle, the Irish invoked ‘their captain’s name or the word of his ancestors’, which in the case of Aodh Ó Néill was ‘the bloddie hand’. In the 1590s Sir George Carew recorded that the title ‘the Ó Néill’ meant more to Aodh Ó Néill ‘than to be entitled Caesar’.

The battle flags associated with Aodh Ó Néill’s armed forces probably consisted of a cross on a white field but, since they do not appear to have been depicted in writings or illustrations of the time, it is not possible to say whether Ó Maolchonaire’s subsequent adoption of the Red Hand of the Uí Néill was inspired by Gaelic imagery used during the Nine Years’ War. Nonetheless, his crest owes more to ancient Irish tradition than it does to contemporary Catholic symbolism, such as the papal military ensigns brought to Dingle by James Fitzmaurice in 1579.

As the jersey worn by Tyrone’s Joe McMahon (in action here for 2008’s All-Ireland winning team) and the loyalist murals of the Shankill Road show, claims to the Red Hand of Ulster have been contested for centuries.

Following defeat at Kinsale, the destruction of the Tullach Óg inauguration seat and other symbols associated with Aodh Ó Néill’s political authority formed an important part of Lord Deputy Mountjoy’s military campaign in 1602. To assist in the ensuing reduction of Ulster, James I instituted the order of baronets on 22 May 1611, whereupon a Red Hand emblem, albeit the left hand, was incorporated into the badge of the Ulster king-at-arms in Ireland and the armorial coat of the baronets.

From the time of his accession to the see of Tuam until his death twenty years later, Ó Maolchonaire’s continued allegiance to the Uí Néill bloodline was staunchly criticised by the Catholic archbishop of Armagh, Peter Lombard, and his allies. Ó Maolchonaire remained in exile waiting for a change in policy towards Ireland, but his aims and those of Aodh Ó Néill were incompatible with ‘the desired stalemate’ for Spain.

Those engaged in early modern diplomacy fulfilled the role of cultural intermediaries whose perennial duty was the defence of their culture’s reputation. With his Red Hand seal at the Spanish court, Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire articulated the views of many Irish exiles and was a ‘living letter’ for Aodh Ó Néill. In the immediate context of the times in which it was put to use by Ó Maolchonaire, the Red Hand of Ó Néill was selected for its ancient historical and cultural connotations, attesting the enduring relevance of such symbolism to its early modern audience. HI

Benjamin Hazard is Louvain 400 Postdoctoral Fellow at the UCD-Ó Cléirigh Institute.

Further reading:

M. Kerney Walsh, Destruction by peace (Monaghan, 1986).

F. Mac Giolla Easpaig et al., ‘The history of heraldry in Ireland’ (The Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, National Library of Ireland, Dublin).

H. Morgan, Tyrone’s rebellion: the outbreak of the Nine Years’ War (Woodbridge, 1993).

D. Ó Cróinín et al. (eds.), A New History of Ireland: prehistoric and early Ireland (Oxford, 2005).

This article is based on the 2009 winning entry to the Irish Chiefs’ Prize in History. For details of 2010’s competition see the notice below.