1609: the Ulster Plantation in the Iberian context

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2009), Volume 17

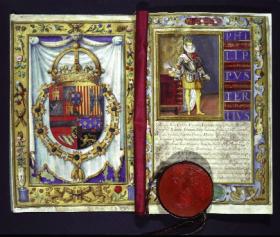

King Philip III of Spain—in 1609 he expelled the Moriscos and in a vast international operation forced around 300,000 people to leave the Iberian Peninsula, mostly to Ottoman North Africa. (Prado Museum, Madrid)

The Ulster Plantation was a complex system of double resettlement: from Britain to Ireland and from Ireland towards the Continent (an estimated 100,000 in the first half of the seventeenth century). Roughly half of these Irish migrants ended up settling in territories controlled by the Spanish Habsburgs, achieving remarkable success and acceptance, although many more found only the misery and deprivation from which they had attempted to escape. This article looks at the ongoing processes of change inside Spanish territories that affected the environment in which these Irish migrants struggled. In 1609 this transformation crystallised in three major interrelated events: the expulsion of the Moriscos; the Twelve Years’ Truce with the Dutch United Provinces after 40 years of war; and the beginning of a withdrawal policy in the New World linked to the transformation of Iberian intercontinental trade.

Expulsion of the Moriscos

The Moriscos of Granada rebelled in 1568 in protest at the abuses inflicted by the Christian authorities aiming to restrict their language and customs. Philip II suppressed the revolt with great difficulty, fearful throughout that the Ottoman Empire would send assistance to the rebels. After the war, the Spanish monarch deported and dispersed the Moriscos around the Iberian Peninsula, primarily to the lower Andalusia valley, New Castile and Extremadura, in order to break down and divide the closed circles of Morisco solidarity and to dissolve the cultural community into a wider Christian majority. When the survivors of the war and the long winter marches reconstructed their communities in hostile urban societies (not previously accustomed to a Morisco population), public awareness of the ‘Morisco problem’ grew, together with pressure on the Crown to resolve it permanently. Philip III finally took the decision to expel them in 1609 and, in a vast international operation, forced around 300,000 people to leave the Iberian Peninsula, mostly for Ottoman North Africa. An undetermined number of them died in the process, an outcome defined by some historians as ‘ethnocide’.

On their arrival in the Iberian Peninsula, the Irish did not fail to see parallels between their situation and that of the Moriscos. Key royal officials such as García Sarmiento de Sotomayor and Count Caracena, who advocated allocating resources to the Irish arriving in Galicia in north-west Spain, had at the same time been charged with expelling the Moriscos. The void left by these evictions created some direct opportunities for the Irish newcomers, although these took time to materialise. It was not until the 1640s that Madrid drew up plans to use Irish settlers to repopulate areas of the Ebro valley that had remained uninhabited since the Morisco expulsion. From the beginning, however, the Moriscos served as the perfect analogy to explain the conflicts in Ireland to Spanish audiences. Describing the rising of 1641, Irish Catholic publications compared the Protestants in Ireland with the Morisco subjects of the Spanish monarchy: both were presented not only as disloyal but also as a mortal threat to the very survival of the political community. Presented in this light, the violence against Protestants aroused little protest in Spain.

The Twelve Years’ Truce with the United Provinces

The expulsion of the Moriscos can be linked to another major event that transformed the Spanish empire by 1609: the signing of the Twelve Years’ Truce with the United Provinces, which concluded 40 years of war precipitated by the Dutch Revolt. Although the truce did not result in a final peace, it did allow both sides time to replenish their exhausted military and economic resources. The Spanish monarchy in particular needed to relieve its economy of the heavy burden of multiple wars in Europe, the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. The truce, along with the Treaty of London (1604), which brought an end to two decades of conflict with England, provided the necessary breathing space. A court faction headed by the duke of Lerma, royal favourite of Philip III, supported the agreement with the Dutch, which tacitly recognised the independence of a Protestant republic. Many historians have argued that the decision to expel the Moriscos provided a smokescreen to divert attention from the controversial terms of the Dutch agreement that had been signed the very same day—an expulsion that purified the body politic and reinforced its religious unity at a time when the power and thus the divine protection of the Catholic monarch was increasingly in doubt.

The terms of the agreement with the Dutch had important ramifications for the manner in which the Irish integrated into Spanish territories, especially outside Europe. From the beginning of the revolt in 1568, Irish Catholics had fought for the Spanish, while the English monarchy had supported the Protestant Dutch. The Netherlands, therefore, provided another battlefield on which Catholics and Protestants fought for the body and soul of Christendom, a continuation of the battle lost in Ireland. The changes crystallised in the 1609 truce, however, presented new and unforeseen opportunities for advancement for Irish migrants. It put in motion long-term changes in the complex relationship between the Netherlands and Spanish territories, both in political and especially in economic terms.

Trade did not stop altogether during the war, but had been severely hindered and carried on largely through smuggling. Now unburdened by any restrictions, it developed at an unprecedented level, allowing Dutch traders to assume a dominant position in Spanish marketplaces. One of the hardest points of the negotiation was the Dutch trade with the extra-European Hispanic dominions. The treaty did not envisage any right for the Dutch to trade in the Spanish territories in America, but in practice they encountered few difficulties. By utilising middlemen in the legal trade in the monopoly routes established by the Spanish monarchy, the Dutch illegally sold their cargo through American ports without paying any duty to the Spanish, who tolerated this evasion for strategic and political reasons.

In this new context inaugurated in 1609, the Irish arriving in the New World changed their attitude towards the Dutch from one of religious confrontation to one of economic collaboration or even symbiosis. The Irish colonies created in the Amazon basin during the first decades of the seventeenth century became completely dependent on Dutch assistance for provisions and the commercialisation of their produce. Moreover, Irish migrants to the British Caribbean settlements who wanted to migrate to Spanish settlements relied on the Dutch to obtain a safe passage from one island to another in exchange for economic collaboration. Confronted by the Spanish authorities, the Irish newcomers would defend the Dutch captains who had brought them as their friends and saviours. One senses an intimate understanding or tacit alliance in the Spanish American world between the Dutch (illegal) traders, smugglers and corsairs and the Irish who settled there and rose to positions of military and political importance.

Spanish withdrawal policy in the New World

The 1604 Treaty of London brought an end to two decades of conflict with England, which, along with the truce with the Dutch United Provinces, relieved the Spanish monarchy of the burden of multiple wars in Europe. (Public Record Office, Kew)

How had the Irish managed to hold such important positions in the Spanish Americas? Here, too, the adjustments around 1609 proved crucial, as the early decades of the seventeenth century in the Spanish Americas saw a change from episodic or spasmodic raids and expeditions by non-Iberian powers to the foundation of permanent settlements and the formation of stable routes of illegal trade. In an attempt to defend its monopoly in the New World, the Spanish monarchy reorganised its defence, settlement and communication systems. This involved abandoning the more exposed or under-populated territories and regions to concentrate military resources on cities and wealthy lands that could be reasonably well protected. From 1609 the Spanish initiated the deliberate depopulation and transfer of settlers from many frontier territories in the tropical forests of the Caribbean islands to the cold southern wasteland of present-day Chile. This policy would, in the long term, bring unexpected but beneficial opportunities for Irish integration in the Spanish Americas.

The forced depopulation of certain territories created spaces in which non-Iberian European migrants could settle. That was the case in the eastern and northern parts of the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), where buccaneers, smugglers, corsairs and pirates found a safe haven from which to launch attacks on, or trade with, the Spanish Caribbean. In response, the Spanish welcomed any relatively trustworthy newcomers, such as the Irish, particularly if they had European military experience that could be put to work in the New World. In many cases the Irish migrants defined themselves as farmers or labourers, but at the same time boasted of their many years of service on the battlefields of the Netherlands or the Iberian Peninsula under Spanish command. This precious ability allowed a fast-track promotion (social, economic and political) to those Irish settling in Spanish America, especially in those areas most exposed to European raids and trade.

Related to this development, in 1609 the state-sponsored trade convoy system, the Carrera de Indias, started a long process of decline after the zenith it had reached the year before. The long-term changes in Iberian transoceanic trade signified a shift to illicit trade outside royal control and dominated by non-Iberian merchants. The Bay of Cadiz became one of the main operating areas of these new commercial networks, where they could load and unload cargos without much fear of Spanish government interference. In the decades after 1609, Irish traders became profoundly integrated into the transnational network of trade (including the slave trade) and smuggling that criss-crossed Europe, Africa, Asia and America. They profited from their ambiguous status as subjects of the British Crown and religious protégés of the Spanish monarchy, as well as holders of significant military and political positions and members of strong patronage networks within the Spanish empire.

All these events presaged profound ongoing transformations within the kingdoms and territories under Hispanic rule, their relationship with other countries and, of the utmost significance, the manner in which Irish newcomers integrated into the Spanish world. Even at the cost of important symbolic, political and economic sacrifices, this new approach provided a realistic opportunity for the Spanish monarchy to keep its position as the first European power. In the Americas, this meant that Spanish claims shifted from defence of exclusive access to the New World at any cost to tacit toleration of European settlements in areas not previously conquered by Spain. All these changes meant that the Irish found an attractive destination in an empire at the zenith of its wealth but in which the vulnerability and symptoms of change were already visible, providing new opportunities, sometimes unexpected and at times very profitable, to all those Irish migrants who possessed the necessary skills, contacts, resourcefulness and risk-tolerance to prosper in an uncertain environment. It is understandable, therefore, that in this context, while many Irish migrants arriving after 1609 experienced economic despair and social marginality, others achieved spectacular social and economic success. HI

Igor Pérez Tostado lectures in history at Pablo de Olavide University.

Further reading:

P.C. Allen, Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598–1621: the failure of grand strategy(New Haven & London, 2000).

A. Feros, Kingship and favouritism in the Spain of Philip III, 1598–1621 (Cambridge, 2000).

E. García Hernán, Ireland and Spain in the reign of Philip II (Dublin, 2009).

M.E. Perry, The handless maiden: Moriscos and the politics of religion in early modern Spain (Princeton, 2005).