Dublin’s Great Explosion of 1597

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Hugh O'Neill, Issue 3 (Autumn 1995), Volume 3![Wood Quay in the late sixteenth century, showing the crane to the right.(from Jonathan Bardon and Stephen Collin(illustrator),Dublin:One Thousand Years of Wood Quay[Belfast 1984])](/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Dublin’s-Great-Explosion-of-1597-1.jpg)

Wood Quay in the late sixteenth century, showing the crane to the right.(from Jonathan Bardon and Stephen Collin(illustrator),Dublin:One Thousand Years of Wood Quay[Belfast 1984])

Sir William Russell,Lord Deputy 1594-97.

(Courtesy of Woburn Abbey)

Smoking crater

Suddenly, in a blinding flash and a thunderous roar the scene was one of devastation. A smoking crater denoted the place where 140 barrels of gunpowder had been stacked. The crane and cranehouse had been obliterated. Everywhere there were strewn shattered bodies and parts thereof. Many of the stout cage-work houses of the merchant patricians which had proudly fronted the river were flattened or almost totally ruinous. Back from the Liffey in the maze of streets and lanes of the city venerable buildings and churches as well as private houses were displaying signs of the blast. An eerie stillness lay over the zone where the explosion had been centred, broken then by the shouts and alarms of those who came to rescue and inspect. To all, the instrument of death and destruction was evident: the gunpowder. What was not immediately obvious was the cause of its detonation. Nor could the far-reaching consequences of that fateful happening be known to the surviving citizens of that already sorely-tried city of Dublin.

It was several days after 11 March when the exact number of casualties was established. There were many non-natives among the dead, and some headless corpses were impossible to identify. The first report of 200 killed was found to be an overestimate and eventually a figure of 126 dead was settled on. Of these, seventy-six were citizens —men, women and children—and fifty were ‘strangers’. Amongst the casualties were the craner, Stephen Sedgrave, his wife, Joan, and three of their children who lived in the cranehouse which was at the vortex of the explosion. The Sedgraves are commemorated in a handsome funerary monument in St Audoen’s church. A Captain Ratlyfe, master of a boat from Chester, was among the visitors killed, as were three of Sir George Bourchier’s men who were supervising the unloading of the barrels. To put the number of citizens killed in perspective, we must realise that the population of Dublin in 1597 was probably much less than 10,000. It is possible that up to one per cent of the population perished on that March afternoon—equivalent to 10,000 of Dublin’s population today.

Dereliction of duty

In the week following the mayor, Alderman Michael Chamberlain, examined at least two dozen witnesses as to the background and circumstances. The fact that so many who had been closest to the scene had died was a great handicap in establishing what caused the casks to go up. It became clear, however, that the clerk of the storehouse of the munitions, John Allen, a royal official, was a central figure in the chain of events which led to the explosion. At the very least he was open to the charge of dereliction of duty as he had left the scene shortly before to ‘drink a pot of ale’ at the house of Alderman Nicholas Barran, according to a merchant examined by the mayor. This witness stated that he met Allen on the quay shortly after the explosion and asked him what had happened. Allen replied that he did not know. The more serious allegation directed against John Allen, and the one for which he was imprisoned in the Castle, was that he had permitted a large quantity of gunpowder to be piled up in the street without having the barrels carried off as soon as they were landed. The reason for the pile-up was a strike among the porters and carters who were protesting against the bullying tactics of Allen and his assistants and the poor wages they were paid.

The Sedgrave family funerary monument,

St Audoen’s. (Brigid Fitzgerald)

Intimidation and exploitation

On examining the bearers who worked along the quays, Mayor Chamberlain uncovered a story of intimidation and exploitation. Interestingly most of these casual labourers had Gaelic names, such as Neale O’Molan, Derbie O’Ferrall and Rorie Dowgan, and therefore belonged to a sub-culture which had no official recognition in the civic records. They complained that on several occasions before 11 March they had been press-ganged into bearing laden and unladen barrels from the quay to the Castle by John Allen and his servants. They frequently used violence or the threat of violence to force the bearers to comply. Rorie Dowgan had been threatened at the point of a dagger and compelled to labour for two full days, carrying explosives from the crane to the Castle. He and his fellow-bearers, who corroborated his account, did not receive a penny until the end of the second day. At a rate four-and-a-half pence per man per day their remuneration was almost half the official municipal daily rate for a labourer. On several other occasions, according to Thomas and John Walshe, the bearers worked at carrying or cutting lead in the Castle and received no recompense at all. Patrick Morisoe testified that he was often forced to labour under threat of blows by Allen and his men, and to accept in wages whatever sum the clerk decided upon when the work was done.

Playing with gunpowder

It is not surprising then that the bearers were refusing to carry the barrels of powder to the Castle in the forenoon of 11 March. One merchant, Patrick Dixon, requested a group of them standing idly at the quayside to bear some boxes of herrings from the crane to his house. They refused, saying that they dared not approach the unloading area for fear of being beaten by John Allen who would press them into service for uncertain wages. Thus the barrels accumulated in the three hours up to one o’clock, stacked up beside the crane. Lax security and safety standards were concomitant factors. The route to the Castle for the few barrels that were transported was through the busiest thoroughfares of the city. On that day, however, even more dangerous practices were noted. An English merchant, James Fox of Manchester, testified that he saw a man rolling the barrels from the crane accompanied by two young children. The youngsters kept the barrels rolling, as if in play, until they came to the place where the cargo was stacked. Richard Tobin, the master porter of Dublin, also referred to the rolling of the barrels by ‘children of the streets’ while harassed crown officials were busy at the crane. One of the most plausible reasons for the disaster was this heedless playing with the gunpowder. The fact that the shippers of the consignment from London had used only single casking, and not double casking as had always been the case theretofore, made the chance of an accident all the greater. The very dry weather conditions were seen as providing the other element in the lethal mixture of factors, besides misuse and faulty packing. Speculation ran that a spark created by a horse’s foot striking the hard ground at the dockside might have ignited the casks.

Sabotage?

Another possible cause, briefly canvassed to be summarily dismissed, was sabotage. Sir John Norris stated in a letter two days after the explosion that there was ‘little appearance that this should happen by any practice, the time being so short that it lay in the place, and the same guarded’. The same thought crossed the mind of Lord Deputy Russell, as is evident from a letter he wrote a week later, but he tended to favour the theory that the firing was accidental, most likely the result of a horse’s hoof striking a spark from the cobbles and freakishly catching some powder. Russell did mention that the imprisoned clerk, John Allen, ‘is suspected to be a recusant’, but he blamed him for his negligence rather than his malice. There were sympathisers with Hugh O’Neill’s campaign against the Tudor regime in all ranks of the citizens up to that of merchant-alderman. Within months of the explosion two leading merchants and two aldermen were questioned by the state authorities in connection with the alleged running of guns to O’Neill. Certainly the business connections between John Allen and the more eminent patricians were examined closely in the wake of the disaster.

A search of Allen’s home revealed that he had some gunpowder and many pieces of armour in his private possession. Besides the city sheriffs who had dealt with Allen legitimately in securing supplies of gunpowder, lead and matches for civic musters and expeditions, other prime citizens were found to have purchased powder from Allen through the Castle storehouse or at his private residence. Two of the merchants who had been thus supplied, Aldermen Robert Panting and Walter Galtrim, were among those suspected of dealing with the arch-enemy of the crown. What the records revealed was a lucrative side-line being carried on by the clerk of the munitions which may have indirectly aided the enemies of the English government whose servant Allen was. There is no evidence that the barrels unloaded on 11 March and stacked on the quayside were deliberately fired. It is inconceivable that a citizen would deliberately be an agent of such an outrage given the closely-knit nature of the small urban community, and most unlikely that a saboteur from outside could pass through the tight security shield in force at the entrance gates to the city at the time.

Compensation

It was clear from the moment that the dust began to settle after the great explosion that a massive and costly rebuilding programme would be necessary and that the crane and cranehouse would have to be completely reconstructed. Between twenty and forty houses in the blast zone were flattened. Among these was the residence of Alderman James Bellew. He drew up a suit to the English court for recompense of £1,018-13-4 to cover the loss of his home and furniture. Most damage was sustained by buildings in Cook Street, Fishamble Street, Bridge Street, High Street and St Michael’s lane. Churches within and without the walls received varying degrees of structural damage and many were still in need of repair up to eight years later. The spire of St Audoen’s church was badly damaged and the guild of St Anne which was located in the parish donated £50 for the carrying out of restoration work. No doubt the condition of the city hall, called the Tholsel, already weakened by a great cleft in the eastern flank, was worsened by the force of the explosion. It was reported that virtually no house in the city or suburbs escaped without being ‘marvellously endamaged’, whether in the ‘tilings, small timbers and glasses’. The city council computed the total loss to the community caused by the firing of the ‘queen’s powder’ at £14,076 sterling, a huge sum in the money of the time. A petition was framed in May 1597 containing the claim for damages from the crown as well as other complaints. Recompense was slow to arrive, as the state revenues in Ireland were fully committed to the prosecution of the war.

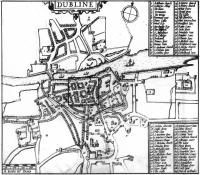

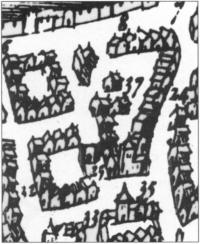

Municipal finances which were already under great pressure were stretched to the limit in the rebuilding of the crane. It was decided apparently to rebuild at the same location and the cost was reckoned at £150. The actual expenditure, involving the importation of Dutch engineers, was twice the original estimate. The corporation had to resort to mortgaging civic properties in order to raise money to pay for the rebuilding, as the community at large was burdened by very heavy taxes. In John Speed’s map of Dublin, dated 1610, there are gaps in the houses in Wood Quay and Winetavern Street, evidence of explosion damage. The credibility of Speed’s work as cartographer has been affirmed by John Andrews (Trinity College, Dublin). His opinion is that the survey of the city for mapping was carried out after 1603, possibly by Sir John Davies, attorney general of Ireland, or by John Speed himself, and before 1607, when land reclamation projects to the east along the river got under way. There is no evidence of these works on the map. If the map can thus be accepted as a historical source, valid for a very specific time, we can draw the conclusion that restoration work was still incomplete within the city up to ten years after the explosion.

Eastward expansion accelerated

Another feature of Speed’s map may identify an alternative trend to restoration within the walls: expansion to the east. Pictured are three important institutions which were established in the 1590s and early 1600s: the college, the hospital and the bridewell. These, in conjunction with the reclamation of lands along the stretch of river between them and the water, placed the emphasis on urban development to the east of the medieval walls. Within another decade and a half the new custom house was constructed on reclaimed land to the north of Dame’s Gate (approximately on the site of the present-day Clarence Hotel). Then, as in the eighteenth century, it was accepted that ‘wherever the seat of trade is fixed, to that neighbourhood the merchants with all their train will in time remove themselves’. Thus it may be that, instead of rebuilding in the cramped environment of the walled city where conditions for commerce were no longer suitable, many merchants opted to build their premises to the east, closer to the new trading facilities. Many of the recently-arrived official families would have had no social or cultural ties with quarters of the old city, and would have been attracted by the proximity of the university. As Dublin entered its phase of rapid expansion in the mid to later seventeenth century, it may have been that the rebuilding necessitated by the explosion damage helped to give an impetus to the easterly tendency in urban development.

John Speed’s 1610 map of Dublin.

One disaster among many

At the time of the explosion Dublin was undergoing a period of socio-economic turbulence, and the suffering, death and damage caused by the gunpowder blast compounded the inhabitants’ problems. One unsympathetic royal official reacted to the explosion in 1597 by calling it ‘a just plague of God for the sins of so impious and ungrateful a people’. This harsh judgement was more an articulation of bleak Puritanism than a specific reference to the failings of Dubliners. In any case they had suffered their share of the three ‘scourges’ sent by God, as they were described by contemporary writers—famine, pestilence and war.

The mid-1590s brought successive cold and wet summers in Ireland. Crop failures from 1594 to 1596 led to hunger in the city and elsewhere. Reports in September 1594 stated that the high price of grain and victuals in Dublin was due to the unseasonable time of the harvest. June to August of the following year were extremely wet and the harvest was spoiled. The cold and wet weather in July 1596 is said to have ruined another. By November 1596 an English official was reporting that the town of Dublin was reduced to poverty. The price of wheat was three times the normal that winter, and reports of famine in the Pale abound for the early months of 1597.

The presence of large numbers of soldiers amongst the population during the years of the great shortage and the explosion compounded the difficulties of the municipality. The report of November 1596 adverted particularly to the continuous traffic of companies of troops from England through the town. Householders were obliged to lodge and ‘diet’ soldiers while they awaited deployment, and the burden of feeding extra mouths was all the more intolerable during the dearth. Repayment of the costs incurred by citizens was extremely slow in coming from royal paymasters, and the daily rate of twelve pence for a soldier’s meals was reckoned to be about a third of the real cost to a household in 1597, given the inflation in grain prices. Compensation fell several years behind, and in 1600 1,200 city households were awaiting recompense for the boarding of soldiers.

It was acknowledged that these delayed payments were a threat to civic order as, according to an observer, ‘all sorts that are to receive pay, and are never paid, do murmur extremely’. But the danger from ill-fed and disgruntled troops was more immediate. Maurice Kyffin reported in early 1597 that soldiers were dying ‘wretchedly and woefully without money, food and apparel in the streets and the highways, far less regarded than any beasts’. The city council was so alarmed at the number of sick troops crowding into Dublin, awaiting passage back to England, that in January 1597 a motion was passed at the civic assembly for the provision of some ‘large house’ to serve as a refuge.

Detail- note the gaps between the houses in Wood Quay.

The arrival of large numbers of troops throughout the 1590s brought with it the danger of infection, and in May 1597 this was given by Alderman Nicholas Weston as the main reason for his projected but never realised scheme for a military hospital. By the following August both city and state records contain many references to a great contagion in Dublin, through an extremely burning fever, ‘whereof many have lately and do continually die’. There may have been a low level of resistance to infection among the populace due to malnutrition in a time of dearth.

Dublin was on a war-footing at the time of the great explosion. Strict security measures were enforced during what the city council called ‘the time of danger’. Physical repairs were made to walls and ramparts, and postern gates were closed up. Each household was to have armour and weapons for a defensive struggle in the event of invasion. The civic armaments were replaced or added to in 1598, and fire-fighting equipment was purchased to replace old stock. To pay for these items and also for a new tent for armed musters of citizens, extraordinary taxes were imposed upon the hard-pressed citizens. In 1596 and 1597 the normally well-balanced accounts of the treasurer show a cumulative deficit of £478. Besides the expenditure of funds on physical defences, the citizens also had to bear the burden of constant watchfulness, contributing day and night patrols of the city’s walls, six gates and suburbs. Eventually in August 1598 a 200 strong civic militia was established to defend Dublin under Captain Christopher Dowdall who was paid twenty shillings per week out of city revenues

Recovery

Thus for at least five years the city of Dublin existed under the threat of outside attack with consequent strains on normal social and commercial intercourse. The explosion was the most devastating in a series of disasters experienced in the late Tudor period. Civic morale was at a low ebb in 1597 as the dead of that March day were mourned, and the independence of the municipality may have received a mortal blow. The civic authorities sought in vain to recover their invulnerability to state intervention in the running of the municipality. But social and economic recovery did occur as a new era of expansion and metropolitan development took shape. The resilience and adaptability of the merchant class was evident in the booming economic conditions of much of the seventeenth century. The population which had been so prone to demographic disaster in times of famine and plague began a process of continuous expansion from the early decades of the century. And Dublin began to slough off its medieval skin and don its splendid modern guise.

Colm Lennon lectures in history at St Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

Further reading:

J.H. Andrews, ‘The oldest map of Dublin’ in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, lxxxiii, section c (1983).

P. Clarke (ed.), The European crisis of the 1590s (London 1985).

C. Lennon, The lords of Dublin in the age of Reformation (Dublin 1989).

H. Morgan, Tyrone’s rebellion: the outbreak of the Nine Years’ War in Tudor Ireland (Dublin 1993).