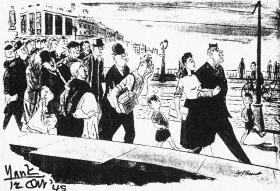

DUBLIN, EIRE[sic] (Yank, 12 October 1945)

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (Summer 2004), The Emergency, Volume 12

‘The centerpiece of this picture was an American sergeant walking across O’Connell Bridge hand-in-hand with a girl in a red dress who looked like Maureen O’Sullivan.’

Eire—It was a beautiful day in Dublin. Floating down the Liffey, neat little barges with red-topped funnels, loaded with brown barrels of Guinness stout, symbolised pre-war living and good appetites. Along the riverside the sunshine accentuated, rainbow-wise, the soft greens, blues, reds and yellows with which Dublin’s tall Georgian houses are painted. It was low tide and, like a green ribbon along the quay wall, a strip of seaweed stretched as far as one could see.

The centerpiece of this picture was an American sergeant walking across O’Connell Bridge hand-in-hand with a girl in a red dress who looked like Maureen O’Sullivan. If he had looked up, no doubt he would have run for his life. Behind him were at least 50 people, seemingly unconscious that together they made a crowd, following in absorbed interest. He was apparently the first American soldier they had seen in Dublin, and the people were in a mood to be carried completely away. The war was over, but the neutral Irish wanted us to know that they were on our side.

Actually the first American soldier to arrive was Capt. Michael Buckley, a chaplain on leave from the Munich area. He arrived two days after Mr deValera’s government had raised the ban on the wearing of foreign uniforms, as a post-war, pro-American gesture, in order to enable Americans with relatives in Eire to visit them before going back to the States.

Some thousands of Americans have visited Eire this summer, but in those early days when the sergeant and his girl drew a crowd, no more than a few hundred had been seen in Dublin. Most GIs who got enough time off to visit had relatives in more remote parts of the country—western Ireland, Galway and Cork.

![“Here’s a man who knows all about [California]”, he said, beckoning to a dyspeptic-looking character on crutches who was leaning against the wall within earshot.’](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/35_small_1245941623.jpg)

“Here’s a man who knows all about [California]”, he said, beckoning to a dyspeptic-looking character on crutches who was leaning against the wall within earshot.’

Things have sobered down some, but GIs are still followed by tribes of wild, ragged, bare-footed children, whose legs and feet look as if they have been lashed with hail and rain—and, as they walk about with bare legs and feet all the year round, they probably are. Aside from that, the kids look in the pink of health.

They are all eager to hear a genuine American accent. A favorite trick is for the leader of a gang to sidle up with a speculative look and ask, ‘What’s the time, mister?’ If it’s your first day in Dublin you look at your watch and say, ‘It’s half-past three’, or whatever it happens to be. At this the kid dashes off with screams of laughter and repeats this in an exaggerated American intonation to the rest of the gang.

About two weeks after the first Americans arrived, a strange distortion of an old battle cry was heard in Dublin. ‘Have you got any gumchum, sir’, the kids asked. They thought that gum and chum were two syllables of the same word. Some old people in Dublin have somehow interpreted the ‘gum, chum’ expression as something you say in America instead of ‘How do you do?’ It is very funny to see old people who have no operative use for the stuff giving you a toothless smile, raising their hats and saying, ‘Have you got any gum, chum’ in greeting.

Every Irishman seems to have some connections in America. The Irishmen stop GIs and say insistently, ‘I lived in the States for fifteen years’, or ‘I’ve sold some property in Rockaway Beach’, or ‘I’ve got a nephew in the American Army in the Pacific’. One outspoken old gent in a tweed suit halted in front of me and said: ‘I’m a veteran of the last war. It’s good to see an American soldier’. As he spoke he looked over his shoulder, and his tone sounded threatening. I thought this strange, then realised that his words were a greeting to me and also a challenge to anyone who might disagree with him. No one did, of course. But it was just another example of the passionate, protesting Irish welcome.

The welcome the students of Trinity College give GIs is a bit on the intellectual side. I was standing on the O’Connell Bridge when two students approached me with: ‘We’re going to a lecture; how would you like to go along?’. Five minutes later I was sitting in a classroom listening to a white-haired professor lecture on the eighteenth-century novel. There were about fifteen students in the room. Some of them were reading twentieth-century novels under their desks. The professor talked for about twenty minutes. Then, in what I can only interpret as deference to me, he swung the lecture from Sterne’s Sentimental Journey to Edmund Burke’s speech in the House of Commons against British taxation of the American colonies. The Irish surprise you with their infinite knowledge of the US. I was walking down Grafton Street when a voice which seemed to come from nowhere called out, ‘Hey, Yank, where you from in the States?’

I looked up and saw an old cab driver sitting cross-legged in the high seat of his horse-drawn vehicle, watching everyone passing by. His derby hat and his hansom cab looked equally battered.

I told him, ‘California’.

‘Here’s a man who knows all about that’, he said, beckoning to a dyspeptic-looking character on crutches who was leaning against the wall within earshot.

The character hobbled over. ‘California?’ he asked, like a bored travel agent. ‘LA or Frisco?’

‘Frisco’, I said.

‘Market Street, Van Ness Avenue, Suter Street, Kearney . . .’ he recited. ‘Christ, I was there before the quake. Then in 1917 for ten years. You know the Mark Hopkins, Fairmont Hotel, St Francis . . . ?’, he asked, reeling off one hotel after another. ‘I was a bellhop there.’

He stopped to look disparagingly at the cabby. ‘He doesn’t know what a bellhop is.’ Then, raising his voice, he said, ‘But I was a bellhop in every hotel in Frisco’.

The cabby broke in excitedly, pointing his whip up O’Connell Street. ‘But did you ever see such a fine-looking street as that, with two lines of such fine-looking tram cars?’, he asked.

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake’, the walking US atlas exclaimed in disgust, ‘do you know that on Canal Street, New Orleans, they’ve got five lines of trams running up the middle—all in one street?’

It was too much. He hobbled back to lean against the wall. The cabby shrugged his shoulders and looked hurt. After a few seconds he said respectfully, ‘That’s Mr O’Rourke. He knows every corner of your country’.

The ‘Gorgeous Gael’, Jack Doyle, with his wife Movita (centre) and friend at the Phoenix Park races c. 1945—‘He wears an orange tie knotted in the Duke-of-Windsor manner and a suit which is so draped in shape that it is far more characteristic of Lenox Avenue, New York, than O’Connell Street, Dublin.’ (RTÉ Stills Library)

Later on I met a character who professed more than just a passing knowledge of the US. He introduced himself by showing me an Irish penny. ‘Gimme another one, bud, for a cup of cawfee’, he demanded in a strong nasal accent, heavily affected. He added piteously, ‘I’m an American on the rocks’.

The next day I bumped into him again. When he made the same approach, I pointed out that we had been through this routine only yesterday. ‘Ah, that’s okay’, he said. ‘I’ll be seeing you again in Vancouver, Montreal, New York’—implying that he would pay me back when we ran into each other again in this small world.

The big story in the Dublin papers on the day I arrived was about a local boy who was up on charges in the Children’s Court for stealing a book from the public library. The book was about tanks. His father pleaded that the court be lenient, explaining that his son had ‘gone mad on tanks’ as a result of a long correspondence with US generals.

To prove it, he showed the judge a letter his son had received from General Gerow of the US Fifteenth Army. The boy had written to General Gerow congratulating him on his direction of the fighting during the Battle of the Bulge, and received in reply a letter from the general’s aide stating, ‘General Gerow is most pleased to receive your letter of well wishes’.

The case was dismissed under the Probation Act.

Many of the GIs who come to Dublin are met by representatives of the Irish Tourist Association who offer to show them the town.

To the question, ‘What do you want to see first?’ the GIs generally reply, ‘A filet steak, and after that anything you say’.

However, one group of GIs was a little more specific. When a trip to the Dail (Irish Parliament), Trinity College or Guinness brewery was suggested, a GI stepped forward, waved these ideas aside and announced decisively, ‘We want to see Mr de Valera’.

‘Dev!’ the guide exclaimed in alarm. ‘No one ever sees Dev. He’s usually nine-feet deep in private detectives.’

‘Just show us where he lives’, the GI suggested.

‘A Franciscan monk, whom I happened to be sitting next to in a train, tapped a parish priest on the knee to enquire if he had seen Going My Way.’

The guide took them to the door and set out, shaking his head sceptically.

But the next day Dublin citizens reading their morning papers whooped, ‘Well done!’ like a defeated English cricket team. The paper said that the American soldiers had an informal chat with An Taoiseach, which lasted fifteen minutes. The Americans said they had no trouble at all. Mr de Valera went out of his way to welcome them and told them if they were ever in the country again to be sure to drop in.

The film Going My Way is a big success in Dublin. The week I was there it was playing in a movie house just around the corner from the famous Abbey Theater, where Barry Fitzgerald and his brother, Arthur Shields, started their careers. Everyone seems to think a great deal of it. A Franciscan monk, whom I happened to be sitting next to in a train, tapped a parish priest on the knee to inquire if he had seen it.

The priest said he had, and nodded appreciatively.

‘Yes’, the monk sighed reminiscently, ‘for me that was It’.

Gasoline is very scarce in Eire, so you don’t see many cars or buses. In Dublin people queue up for transportation. The shortage of gas has given birth to a new industry—not, as you might think, cheaply manufactured bicycles; but street musicians who entertain the people who have to wait in the queues. You see the musicians in almost every block, generally a husband-wife-and-child team. The wife sings, the husband accompanies her on the accordion, and the child sells the lyrics or sheet music. Such teams are said to make about a pound a day.

The most popular ballad is ‘Lily, the Lamp Lighter’, better known in the rest of the world as ‘Lily Marlene’.

There is a cigarette shortage, too. When GIs go into a tobacconist in search of cigarettes they are often told, ‘Sorry, sir, we’ve only got American’. This rather disparaging tone is not meant to be offensive, and if you decide to buy a package of American cigarettes you see what the tobacconist means. Chesterfields and a number of other popular brands are stale. Apparently, they have been in stock since the war started. Other American cigarettes are brands which sprang up in the States during the shortage. If the tobacconist sells you these he adds jokingly, ‘I can get a coffin for you wholesale’.

One of the most colorful characters in Dublin is Jack Doyle, the Irish boxer. The Irish call him the ‘Fighting Canary’ because he has combined his career with crooning during the last few years. He wears an orange tie knotted in the Duke-of-Windsor manner and a suit which is so draped in shape that it is far more characteristic of Lenox Avenue, New York, than O’Connell Street, Dublin.

The fact that singing takes up a lot of his time makes his old opponents resentful. There is a story that he was singing ‘Mother Machree’ in Tuam, Galway, one night when Martin Thornton, the Irish heavyweight champion, challenged him from the audience. Doyle paid no attention at first, but he was interrupted so many times that he was forced to stop the performance and accept the challenge, making a date for one fight in Dublin and one in Galway.

It’s practically unfair to describe the food in Eire. Most GIs and a good many of their families back home have forgotten what such food and drink taste like. There are, as the British say, lashings of whipped cream, salmon, chicken, eggs, milk and tender steaks as large as doorsteps.

In a restaurant called Jammet’s, there are 80 different items on the menu. The last thing I remember eating there was ice cream mounted on whipped cream, mounted on strawberries, mounted on meringue.

The bars are full of whisky, Portuguese sherry, brandy, gin and liqueurs. After seeing the empty bottles which decorate the shelves in British pubs, this sight is a bit overpowering.

Scenically, Dublin is a lot like Paris. It has wide, sweeping streets and a river running through the town arched with delicate white bridges. It has a non-commercial atmosphere, with no soot, no factories.

All this was summed up in a bit of understatement by Mr Eugene O’Brien. His pub is across the street from the Abbey Theater.

‘And what do you think of Ireland?’ he asked three GIs who had just walked in. They went into raptures, using superlatives more characteristic of Hollywood trailers than ordinary GI conversation.

He listened, then bought them three drinks and sat down opposite them to think it over.

‘Well’, he said finally, ‘it’s not such a bad little island. It’s a lot better than some of those in the Pacific.’