DUBLIN CITY UNIVERSITY 1980–2020: designed to be different

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 6 (November/December 2020), ReviewsEOIN KINSELLA

Four Courts Press

€45

ISBN

Reviewed by Colum Kenny

Colum Kenny BL, professor emeritus, is a former chairperson of the Master’s in Journalism at Dublin City University.

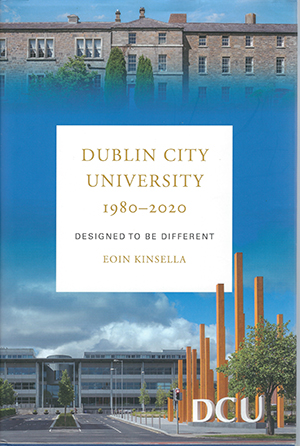

This book’s cover and a block of glossy, coloured photos define it. At the top of the jacket is the Victorian Albert College, once an agricultural science building but now central to the main DCU campus. Underneath is a modern aspect of the university. Here is a standard institutional history. The single block of shiny photos brutally highlights its commissioned origin: twelve big men and six buildings. All five male chairmen/chancellors to date are included. The only female one, the late Mella Carroll, is not. Reference to an insignificant minor ‘criticism’ of that highly respected judge is her sole mention in the text itself.

This book’s cover and a block of glossy, coloured photos define it. At the top of the jacket is the Victorian Albert College, once an agricultural science building but now central to the main DCU campus. Underneath is a modern aspect of the university. Here is a standard institutional history. The single block of shiny photos brutally highlights its commissioned origin: twelve big men and six buildings. All five male chairmen/chancellors to date are included. The only female one, the late Mella Carroll, is not. Reference to an insignificant minor ‘criticism’ of that highly respected judge is her sole mention in the text itself.

The ‘great man’ concept of history does a disservice to DCU, which won its spurs through decentralised schools or departments and built its innovative courses and reputation from the ground up. Presidents and chancellors helped. Begrudgery and snobbishness at older universities did not.

Eoin Kinsella forcefully reminds the reader of the levels of political indecision and confusion that are a familiar aspect of Irish state policy and that hampered the creation of the new university. However, DCU’s first president, Danny O’Hare, had certain skills suited to navigating these. His two successors steadied the ship.

The government’s definition of ‘a technological university’ or even of ‘technology’ was never precise. This allowed DCU’s School of Communications, for example, to eschew any narrow expectation of mere ‘hands-on’ training. The experience of students on ‘Intra’ work placements quickly demonstrated that ideas, analytical ability and initiative were also crucial. DCU faculties were likewise to the fore in Ireland in facilitating study abroad.

Kinsella writes that it would take a multi-volume history to devote ‘adequate time’ to the work of each DCU school and that he has ‘not drawn deeply’ on their records. His account might have been more firmly rooted in such work, for their efforts soon attracted, proportionately, the highest ratio of applications per available first-year place of any third-level institution in the state.

Much detail in the chapters on curriculum and buildings could have been synopsised, and some appendices omitted, to create space for a more critical and dynamic focus on livelier matters such as tensions between faculties or strains within schools when they debated decisions at the cutting edge of Irish education. Broader issues like the criteria for—and quality control of—career development in the public sector, the awarding of honorary doctorates (DCU’s first was to Charles Haughey!) or deals like that between the NIHE/DCU and SIPTU that forced all employees into just one union (thus excluding IFUT) also merit analysis.

In 1982 the founding head of the School of Communications, Tim Wheeler, recruited me into what was, characteristically for the new institution, a cross-disciplinary and exciting faculty. Others who later joined included John Horgan and Helena Sheehan, the latter currently completing a second volume of a memoir that contains a sharp critique of DCU. As a former RTÉ journalist, I soon applied to the minister for a radio licence for students. He promptly refused, pointing to RTÉ’s continuing monopoly, even in the 1980s. He thus highlighted the State’s conservatism, despite its aspirational jargon.

When DCU did later get a radio licence, this was firmly embedded within the university and not sustainably integrated into the surrounding area. Kinsella’s chapter on ‘the university in the community’ is worthy if generous, and a reminder of how far removed from effective equality of access to education citizens still are. For corporate funders and government ministers, equality of access is sometimes little more than a public relations gloss.

A striking omission is a textured chapter on research, although significant successes for DCU in winning PRTLI (Programme for Research in Third-Level Institutions) and SFI (Science Foundation Ireland) funding are noted. The tracking or even listing of two annual awards that DCU’s presidents have given staff for research, one in the ‘hard’ sciences and one in humanities, would have provided a fuller idea of what has been achieved despite the demands of teaching and other constraints.

As regards ‘philanthropic’ donations, not all funders are as ostensibly benign as Atlantic’s Chuck Feeney—deservedly acknowledged here. Who sets agendas? There is much that could be learnt from DCU about the broader relationship between public and private sectors when it comes to university funding and research, and the need not to devalue teaching when desperate for money.

DCU was ‘designed to be different’, as the book’s subtitle indicates. Kinsella has written usefully of aspects of an Irish institution that reflect changes in Irish education and society since 1980. These include the successful integration of St Patrick’s College, Mater Dei and the Church of Ireland College of Education into a university that started just 40 years ago as a small but ambitious project—located (as one senior RTÉ executive who was invited to give a guest lecture once told me) ‘out in the sticks on Dublin’s northside’.