Dependency claims for the Civil War executed in the Military Service (1916–1923) Pensions Collection

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2018), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 26There is much in these files for researchers and academics to grapple with for some time to come, proving that the MSPC is an essential source for any serious student of the Irish Revolution.

By Michael Keane

The latest release from the Military Service (1916–1923) Pensions Collection (MSPC) has made files relating to 73 of the 81 executed between 17 November 1922 and 30 May 1923 during the Irish Civil War available to the researcher. Files of any type relating to the remaining eight Civil War executions remain to be found. This article will look mainly at the background to the creation of these files, their purpose and the type of material contained within. It will concentrate on those files created under the Army Pensions Acts and will very briefly consider some of that information and the insights provided and questions raised.

The origin of the files relating to Erskine Childers and Peter Cassidy (4 Battalion, Dublin Brigade, executed at Kilmainham on 17 November 1922) differ from those for the other 71. Childers’s files were Department of Defence files created in the context of his arrest and execution and its aftermath. The file relating to Cassidy was created as the result of an application for the posthumous award to him of a service (1917–21) medal by his sister. The files relating to the other 71 were created as a result of applications under the Army Pensions Acts from relatives of the deceased seeking allowances or gratuities as their dependants. Thus the files relating to Childers and Cassidy, and the information and documentation contained within them, differ greatly from the rest.

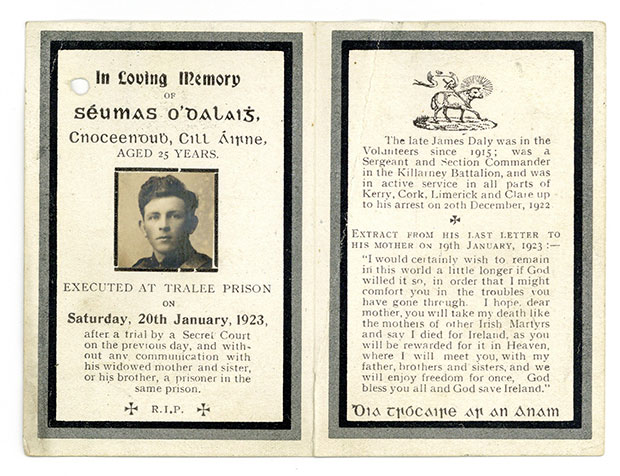

Above: Memorial card for James Daly, executed on 23 January 1923 at Tralee. As many Civil War deaths, including executions, were not registered, in memoriam cards were submitted in lieu by dependants as proof of death. (Military Archives)

Eligible relatives

Applicants claiming as dependants under the Army Pensions Acts had a number of hurdles to cross. There was no automatic reward from the Fianna Fáil government that brought in the Army Pensions Acts of 1932 and 1937 that facilitated most of the claims relating to the executed and to the Republican dead generally. First, applicants had to prove that they were eligible relatives under the legislation: mothers of the deceased; fathers of the deceased over 60 years of age; a widow of the deceased who had not since remarried; a son under the age of eighteen; an unmarried daughter under the age of 21; a brother who was either under eighteen years of age or permanently invalided; a sister who was unmarried and under 21 years of age or unmarried and permanently invalided; and grandparents. Any other type of relative—stepmothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, etc.—was not eligible. Also excluded were mothers if the deceased child was illegitimate.

Eligible relatives had four further hurdles to cross. First, the deceased had to have been a member of one of the organisations specified under the Act—Óglaigh na hÉireann (IRA), the Irish Volunteers, the Irish Citizen Army, Na Fianna Éireann, the Hibernian Rifles or Cumann na mBan. Second, that death had to have arisen either while on or as a result of active service for the organisation. Third, the death could not have been due to negligence on the part of the deceased. Finally, the applicant(s) had to be able to prove dependency on the deceased.

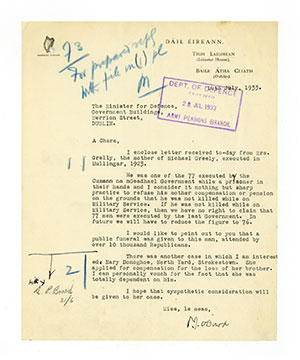

Above: Letter from Fianna Fáil TD P.J. O’Dowd in support of the dependants’ claim from the mother of Michael Grealy. His representations were not successful and Grealy is not recognised as one of the ‘77’. (Military Archives)

All of these qualifying criteria had to be investigated and approved in the case of each individual applicant and their deceased relative by the Military Service Registration Board (MSRB) and the Army Pensions Board (APB) before a recommendation for an award to be granted was issued by the minister for defence to the minister for finance and his department for final approval. Only then was the allowance or gratuity paid out. Nor was Finance’s approval a formality. Indeed, from the evidence on the files in the collection generally, these politically sensitive and emotive dependants’ applications were a source of much friction between the departments and their respective ministers in the 1930s and beyond.

Referees

The Military Service Registration Board would contact referees provided by the applicant to verify the deceased’s membership of the required organisation(s), his service and the circumstances surrounding his death. If the applicant resided within the state, the Army Pensions Board would, initially through customs and excise officers and later through local social welfare officers, as well as occasionally through an officer of their own such as Thomas Markham, secretary of the Army Pensions Board and himself a veteran of the struggle, interview the applicant, investigate the circumstances and means of the family/families of the applicant and deceased, and ascertain the degree of dependency, if any, of the applicant(s) on the deceased. If the applicant(s) resided outside the jurisdiction, clergymen, policemen or other officials of that state might be requested by the Army Pensions Board to provide the necessary information. Alternatively, the relevant Irish legation or consulate might handle matters.

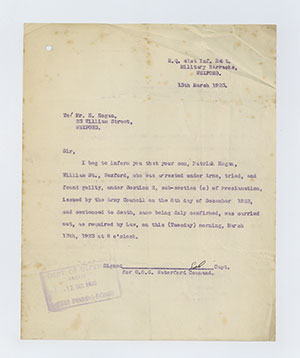

Above: Letter informing the father of Patrick Hogan of his son’s execution in Wexford on 13 March 1923. (Military Archives)

In the case of applications from Northern Ireland, unsurprisingly, officers or employees of that state were bypassed. Sympathetic Catholic clergymen or private citizens were instead approached to carry out the interviews/investigations. The Army Pensions Board would also, where an applicant’s invalidity was in question, oversee and/or organise the necessary medical investigations and examinations.

The documentation created as a result of these investigations is what makes up these files, although a few further points of explanation and clarification need to be made at this stage. First, it was not possible to source all of the documentation created in all of the 71 cases. Potentially significant documentation remains to be sourced for five applications. Second, if an application was found to fail any of the qualifying criteria, investigations into the other qualifying criteria might not always proceed.

All that said, significant and compelling documentation and information has been found in the vast majority of the 71 cases. Previously unknown information regarding the deceased and their families is now available to researchers for the first time.

What sort of information?

So what sort of information is contained in the files regarding the executed? Listed is the number of cases among the 71 where an award was made; the occupations of the executed; their rank/position within the anti-Treaty forces; the units with which they served; and their places of birth or residence. In ten of the 71 cases the applications were unsuccessful. For eight of these ten the claim fell either through an inability on the part of the applicant to prove dependency or because the applicant was ineligible. In the other two cases, of Luke Burke and Michael Grealy, the deceased were judged not to have been ‘killed while engaged in military service’—in other words, the actions that led to their arrest and execution were not officially sanctioned by the IRA. Traditionally, of course, neither Burke nor Grealy have been counted among the 77 Republicans executed.

Interestingly, the files reveal that question marks also hung over the cases of William Conroy, Patrick Cunningham and Columb Kelly of 1 Offaly Brigade—all executed on 26 January 1923 at Birr Castle and traditionally seen as part of the ‘77’. Statements on William Conroy’s file from former Offaly IRA officers Seán McGuinness and Michael Galvin indicate that all three were suspended and awaiting IRA court-martial in relation to alleged indiscipline at the time of their arrest. Indeed, McGuinness goes even further and states that the three ‘committed a couple of minor robberies’, which led to their arrest and execution. Nevertheless, their activities and IRA memberships were recognised and awards were granted to their dependants. Meanwhile, not even strong representations from Roscommon Fianna Fáil TD and former IRA member P.J. O’Dowd, nor a note from a departmental official forwarding O’Dowd’s verbal comment to him that Michael Grealy’s activities had been ‘unofficial but authorised’, could persuade the MSRB in Grealy’s case.

Lower ranks over-represented

Information regarding the deceased’s occupation had to be produced to allow the question of dependency to be fully investigated. The executed came from a wide range of backgrounds and included farmers, farm labourers, civil engineers, clerks, apprentice tinsmiths, insurance agents, blacksmiths, blacksmiths’ helpers and railway engine cleaners, to name but a few. We also get an interesting, though not definitive, insight into the relative ranks or positions within the anti-Treaty forces held by those executed (Table 1). The information regarding rank/position and unit membership is as certified by the MSRB for the time of their capture and/or death, or, in the cases of Childers and Cassidy, from other sources of verification on their files. Luke Burke and Michael Grealy, whose service and membership were not certified for the time of their deaths, are listed as civilians. Both did have some IRA service—Grealy’s was recognised up to the Truce and Burke’s service was recognised for 1922. ‘Member of Active Service Unit’ is the term used by the MSRB for six individuals at the time of their capture and/or execution, even though the IRA nominal rolls in the collection show more than one of them holding officer’s rank at least at company level at the outbreak of the Civil War outside of the Active Service Unit (ASU). Where certification or verification for a rank or position was not found on the file the individuals are listed as ‘Unknown’.

| TABLE 1 | |

| Rank/position | Nos executed |

| Member General Headquarters | 3 |

| General Headquarters Staff Officer | 1 |

| Brigade Officer Commanding | 1 |

| Brigade Staff Officer | 1 |

| Battalion Officer Commanding | 2 |

| Battalion Vice Officer Commanding | 1 |

| Battalion Adjutant | 1 |

| Battalion Quartermaster | 1 |

| Captain | 4 |

| Lieutenant | 3 |

| Company Quartermaster | 1 |

| Sergeant | 1 |

| Section Commander | 4 |

| Driver; machine-gunner | 1 |

| Private | 37 |

| Member of Active Service Unit | 6 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Civilians | 2 |

It is notable that, even excluding the ASU members, a clear majority (43) held non-commissioned officer (NCO) rank or lower, while those at company officer level and above accounted for only nineteen of those included in the collection. Even were all ASU members, the unknowns and the remaining eight for whom files have not been sourced found to be officers, which is very unlikely, the fact would still remain that the majority of the executed came from the ‘other ranks’. Given that there was no shortage of troublesome mid-ranking and senior IRA officers available for execution in the internment camps and prisons at the time, it is—to say the least—interesting that this should be so.

Place of birth, execution and brigade

The breakdown of the executed by place of birth, location of execution and IRA brigade is of interest (Tables 2 and 3). Unit designation is as certified by the MSRB and is shown by brigade where possible. Executions took place in seventeen counties of individuals from 21 of the 32 counties. The high numbers of those executed who were either originally from or served with IRA units in counties Kerry, Dublin or Galway is perhaps not surprising. It is interesting that Offaly and Kildare are so highly represented while counties such as Mayo and Sligo are completely absent, especially given the casualties inflicted on and difficulties posed for government forces by IRA units and individuals from those two counties.

| TABLE 2 | ||

| County/country | Executions carried out | County/country of birth/family residence of executed |

| Dublin | 15 | 10 |

| Kerry | 7 | 9 |

| Kildare | 7 | 7 |

| Westmeath | 7 | 2 |

| Louth | 6 | 6 |

| Donegal | 4 | 0 |

| Galway | 4 | 8 |

| Clare | 3 | 5 |

| Laois | 3 | 1 |

| Offaly | 3 | 4 |

| Tipperary | 3 | 4 |

| Wexford | 3 | 3 |

| Kilkenny | 2 | 2 |

| Limerick | 2 | 0 |

| Waterford | 2 | 0 |

| Carlow | 1 | 1 |

| Cork | 1 | 4 |

| Meath | 0 | 2 |

| Armagh | 0 | 2 |

| Roscommon | 0 | 1 |

| Derry | 0 | 1 |

| England | 0 | 1 |

| TABLE 3 | ||

| Brigade/unit | Nos executed | |

| Dublin Brigade | 7 | |

| Kildare Brigade | 7 | |

| Tuam/North Galway Brigade | 7 | |

| 1 Offaly Brigade | 5 | |

| Mid-Clare Brigade | 5 | |

| North Louth Brigade | 5 | |

| 1 Kerry Brigade | 4 | |

| General Headquarters | 3 | |

| South Wexford Brigade | 3 | |

| 1 Cork Brigade | 3 | |

| 2 Kerry Brigade | 3 | |

| 2 Tipperary Brigade | 3 | |

| 1 Meath Brigade | 3 | |

| 2 (Donegal) Brigade, 1 Northern Division | 2 | |

| 1 Northern Division | 1 | |

| Kilkenny Brigade | 1 | |

| South Kilkenny Brigade | 1 | |

| South Louth Brigade | 1 | |

| Carlow Brigade | 1 | |

| Athlone Brigade | 1 | |

| Laois Brigade | 1 | |

| 3 (Donegal) Brigade, 1 Northern Division | 1 | |

| 4 Western Division | 1 | |

| 4 Northern Division | 1 | |

| General Headquarters Staff | 1 | |

| Civilian | 2 | |

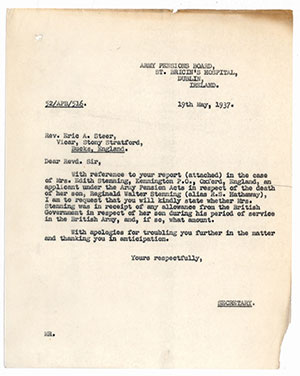

Above: Letter sent by the Army Pensions Board to Church of England vicar Revd Eric Steer, Buckinghamshire, regarding his investigations on the Board’s behalf into Edith Stenning’s application in respect of her executed son, Reginald, a deserter from the British Army’s East Lancashire Regiment who joined the IRA in Kerry. The Stennings’ application was unsuccessful. (Military Archives)

Reginald Walter Stenning

The case of English-born British Army deserter Reginald Walter Stenning, a.k.a. Reginald Hathaway, executed in Tralee on 25 April 1923, is of special interest. Born on 26 February 1903 at 96 Oldfield Road, Willesden, Middlesex, England, Reginald Stenning had no obvious connection with Ireland. Liam Mellows, too, was born in England, but he had Irish parents and was brought up in Ireland. At his trial Stenning claimed to have deserted from the East Lancashire Regiment while serving in the country. Exactly when he deserted is unclear, although the MSRB credit him with service with 1 Kerry Brigade IRA from September 1922. The applications from his parents were unsuccessful, as they could not prove dependency on their son, who—or so his father claimed—had joined the British Army without their knowledge. Incidentally, Stenning is one of seven executed who were former British servicemen. The others are Patrick Mahony, Thomas Murray, John Murphy, Michael J. Fitzgerald, Thomas Gibson and Erskine Childers.

These are just brief glimses of the type of information that can be found in the files of the Civil War executed, and, indeed, in the files of casualties from all the conflicts of the revolutionary period. There is much in these files for researchers and academics to grapple with for some time to come and to prove that the MSPC is an essential source for any serious student of the Irish Revolution.

Michael Keane is Project Archivist with the Military Service (1916–1923) Pensions Project.