Deaf records

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2017), Volume 25By Fiona Fitzsimons

The first efforts to provide education for deaf children and young people in Ireland were voluntary. In 1816 Dr Charles Orpen established the Claremont Institute for the Deaf and Dumb in Glasnevin. The Claremont was under the patronage of the Church of Ireland but accepted Catholic children as students. In the 1830s, controversy between the churches over education spurred religious orders to develop separate deaf schools for Catholic children.

In 1846 the Catholic Institution for the Deaf and Dumb opened St Mary’s, a residential school for girls in Cabra, Dublin, which was managed by Dominican nuns. On 11 January 1846 the first student enrolled: ‘Agnes Beedem aged 8, daughter of John and Kate Beedem of 162 Capel Street, Dublin City’.

From 1849 St Mary’s accepted boys. As the school was residential, the sexes had to be separated. In 1857 a residential school for deaf boys, St Joseph’s, opened in Cabra, managed by the Christian Brothers. Children were accepted from eight years. They came from all backgrounds and all counties. A small number of children were sent to the deaf schools from workhouses, where they had been left as ‘unproductive family members’.

The children were educated through Irish sign language developed in the 1840s from the French system of Sicard and L’Eppe. A peculiarity is distinct signing for men and women. Women’s signs for weekdays made reference to the domestic tasks they performed on any given day. The sign for ‘Monday’, when laundry was done, simulates scrubbing.

Students were encouraged to stay in education long enough to learn a trade. Young women were steered towards domestic service and were taught millinery, dress-making, baking and cookery. Those less adept at the domestic arts were steered towards factory work. Young men learned building and carpentry, cabinet-making, shoemaking, upholstery, saddle-making, gardening and farming. From the 1870s St Mary’s also provided teacher-training for young deaf adults coming through the Cabra schools. Although deaf teachers were introduced as an expedient, they are credited with raising the standard of deaf education in Ireland.

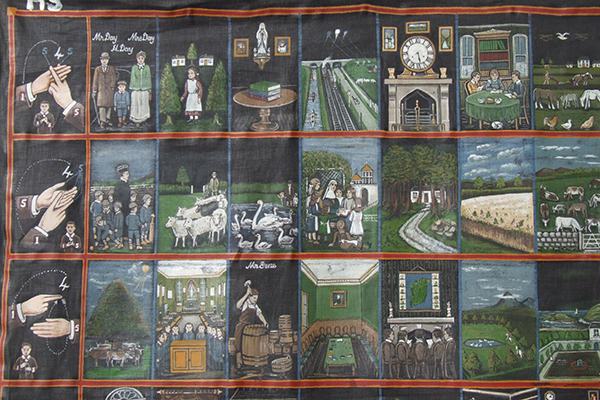

Above: A learning chart for deaf children, painted for St Joseph’s School, Cabra, by a former student. (Deaf Heritage Centre)

The Deaf Heritage Centre in Cabra preserves the heritage of the schools for the deaf. The collection is rich, varied and thought-provoking. It includes from 1847 the annual published Reports of the Catholic Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. These include the names of all students, their parents and identifying information, and dates when children left the school or died. The reports also have lists of donations and subscriptions, in which names, addresses and the sums donated were recorded.

Teachers’ Wages Books include lists of the deaf teachers, 1870s–80s. Deaf teachers ‘lived in’ and were significantly cheaper than ‘hearing’ teachers, the evidence of which is here. St Joseph’s School published Annual Books focusing on the students and school. Other complete runs of journals and newsletters for Cabra alumni living in Ireland or overseas that survive in the Deaf Heritage Centre include Contact News (1979–2003), the Irish Deaf Journal (1987 to present), the Newsletter (from 1983) and the St Vincent Letter News (monthly, 1967–80).

Photographs include glass-plate negatives from the 1890s and prints from the 1920s. Although names are not always on photos, students can usually be identified from St Joseph’s Annuals and other collateral records.

The Deaf Heritage Centre is campaigning to raise money to conserve the building, and to clean, conserve and exhibit its archival collection.

Enquiries: deafheritagecentre@eircom.net.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.