De Valera, censorship and Family and community in Ireland

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2020), Volume 28The Harvard Irish Study, 1930–6.

By Anne Byrne and Eoin O’Sullivan

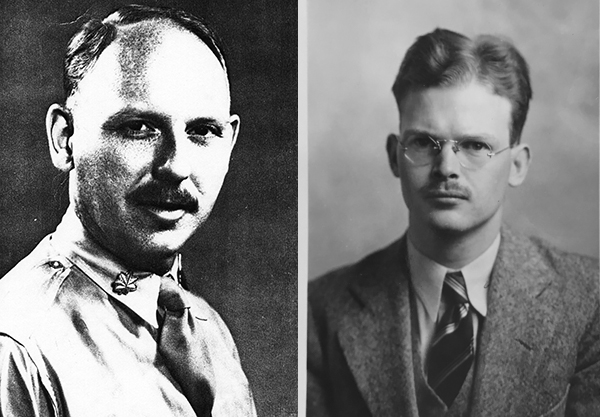

Family and community in Ireland, first published in 1940 by Conrad Maynadier Arensberg and Solon Toothaker Kimball, is one of the most influential texts in Irish rural sociology and anthropology. The Harvard Irish Study (1930–6) was composed of three strands—physical anthropology, archaeology and social anthropology. Family and community in Ireland was the first social scientific research utilising contemporary theory (structural functionalism) and research methods (ethnography, qualitative interviews and secondary data) to be carried out in Ireland or, indeed, Europe.

‘Some word of general approval’ solicited from de Valera

On 14 August 1939, Dumas Malone, director of Harvard University Press (HUP), informed Conrad Arensberg that HUP was happy to publish their work on Ireland, noting that Earnest A. Hooton, director of the Harvard Irish Study, ‘has several ideas about promotion which may be effective’. One of these ideas was an invitation from Hooton to the Irish ‘Prime Minister’, Éamon de Valera, to write a ‘few words by way of introduction’, should the publication meet with his ‘approval’. Hooton suggested that de Valera might refer the about-to-be-published text to an Irish scholar for ‘careful reading’, adding that a declaration of interest by the prime minister of Éire ‘would insure an enormous circle of readers in this country’.

Above: Conrad Maynadier Arensberg (left) and Solon Toothaker Kimball (right), authors of Family and community in Ireland, first published in 1940. (credits?)

De Valera was familiar with the work of the Harvard Irish Study, having met with the Irish director, W. Lloyd Warner, in July 1932. Warner suggested that if de Valera wished ‘to inquire about the sociological and economic part of our research you might refer to Professor George O’Brien, of the National University, since he is well aware of what we are doing and has given it a careful examination, or to Mr Delargy, of the same university’.

De Valera wrote to Malone that he was ‘very glad to look over the work of Dr Arensberg’ but, to be ‘in a position to express an opinion’, he would invite other readers to comment. The page proofs were sent to de Valera and Malone wrote that HUP would be ‘immensely grateful for some word of general approval from you, as this would carry great weight with the American Irish’. He added that an endorsement from the prime minister ‘could be used most effectively on the jacket and elsewhere’.

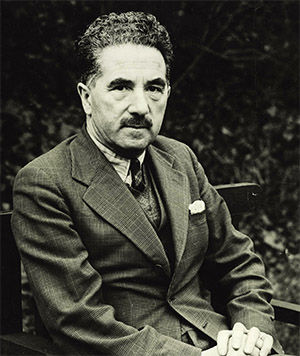

Above: Secretary of the Department of External Affairs Joseph Walshe—the available evidence suggests that Walshe was the sole Irish ‘reader’ of the proofs of Family and community in Ireland, and that he read only the portion selected by de Valera.

In a note dated 23 January 1940, de Valera’s private secretary, P.S. Ó Muireadhaigh, recorded that the proofs had arrived and that he ‘informed the Taoiseach of their receipt on the 10th instant’. De Valera then ‘took [a] portion of the proofs (pages 226–231) with a view to reading them himself’. Ó Muireadhaigh asked de Valera ‘if he had completed their reading but he had not’. When he informed de Valera ‘of the receipt of the letter from Dumas Malone, Mr Walshe, Secretary, Department of External Affairs entered the room. The Taoiseach asked him to have a look over the pages which he, the Taoiseach, had withdrawn.’ If Joseph Walshe did look over the pages and offered advice to de Valera, it is not on record.

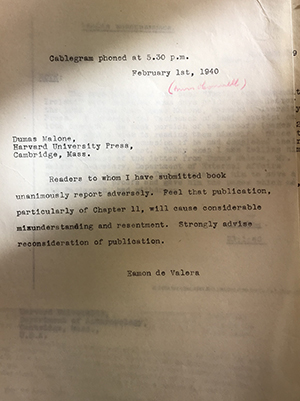

Neither is there anything on file to suggest that de Valera made contact with either of the nominated referees, O’Brien and Delargy. The available evidence suggests that Walshe was the sole Irish ‘reader’, and that he read only the portion of the proofs selected by de Valera. Walshe returned the proofs to the Department of An Taoiseach on 19 February, and a handwritten note from Ó Muireadhaigh stated that he placed the proofs in an ‘envelope marked confidential’. Based on the advice from Walshe, Malone received the following cablegram from de Valera on 1 February:

‘Readers to whom I have submitted book unanimously report adversely. Feel that publication, particularly of Chapter 11, will cause considerable misunderstanding and resentment. Strongly advise reconsideration of publication.’

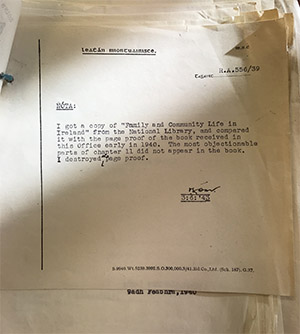

Proofs of ‘objectionable parts’ destroyed … but original survives

Over three years later, when he compared the proofs with the published edition of Family and community in Ireland, Ó Muireadhaigh noted that the ‘most objectionable parts of chapter 11’ had been removed. Ó Muireadhaigh then destroyed the proofs, and hence it was not possible to identify the ‘objectionable parts’ or why they caused de Valera such offence.

A copy of the proofs has survived, however, in the Solon T. Kimball papers archived in Chicago. We can now identify the modifications that were made to chapter 11 and the content of the pages that de Valera ‘took [a] portion of’. The pages selected (226–31) of the proofs were a quasi-addendum to chapter 11, entitled ‘Familism and Sex’. They contained two life-history interviews on marriage, from a countrywoman and a countryman. The pages also included a ‘story of a famous prank, still recited with great hilarity … a classic example of the treatment of the theme of an old man’s marriage’. The ‘prank’ concerned a story of relatives who, fearful of being disinherited by heirs from a second marriage, unsuccessfully attempt to disrupt the sexual relations of their older relative with his young bride.

On learning about de Valera’s cablegram advising reconsideration of publication of Family and community in Ireland, Arensberg was clearly upset. In a letter to Malone he describes the situation as a ‘debacle’, as he had been opposed to the idea of an ‘official imprimatur’ for an anthropological and scholarly text. A couple of months later, in a letter to Warner, Arensberg was more sanguine about the incident:

‘The matter is confidential, but it is also laughable too. Hooton sent the book to Ireland for an official government imprimatur. After a long time, when the book was already rolling off the presses, they cabled: “Chapter XI (that of the one on sex!) objectionable and liking to cause ill-feeling here”. Ha! International incident. That stopped the presses and got the Harvard Press running around furiously getting bigwigs to read the thing.’

Not only did Arensberg delete pages 226–31, which he replaced with an analysis of the class structure of rural communities, familistic norms and constraints on sexual behaviour, but he also made cuts to other parts of chapter 11, some more extensive than others. These cuts invariably mentioned ‘sex’, although it would appear that neither Walshe nor de Valera ever read the entire text of the chapter. Arensberg was not aware that the case histories were all that Walshe had read and reported on to de Valera and that it was these in particular that had caused the ‘offence’.

Above: The cablegram received in February 1940 by Dumas Malone of Harvard University Press from de Valera. (NAI)

‘Countrywoman aged about 50’

The first case history, by a ‘Countrywoman aged about 50’ and her husband, concerns love and marriage. The contrast in accounts is marked. The countrywoman details prior efforts to find a husband while her husband talks of desire, sexual performance and a miscarriage. The countrywoman describes her first relationship with Pretty P., but that ‘[t]here was no life in him, he used to be only talking about cows and calfs and pigs and bonhams; he would not embrace or nothing or even dance’. She started a relationship with T., but that concluded when he asked her ‘would it make any difference for him to go for a Miss F for that night and I to go with some other body? I says, do as you like, if you go for her tonight you won’t have me tomorrow night. So that card was broken up.’ She meets J., whom she calls her ‘lover’ and ‘my love’. A match was made and a fortune agreed but not before the countrywoman searched ‘high and dry’ for a wife for one of her brothers. Her husband takes up the story on the day of the wedding, when he ‘got what he was a long time waiting for’ with his ‘loving wife’. He was ‘fond of her’ and she of him. The couple had three children, and he hoped for more. Ill-health affected his sexual performance: ‘… I got some attack and fell to the ground. I was laid up then afterwards for a long time. About a year afterwards, there was something else born for us. I could not say whether it was a boy or girl. She got too strong then for me, and that’s why I haven’t any family since, but I am now recouping in health, thanks be to God, and I hope to knock a few “gets” more out of her.’

Above: De Valera’s private secretary P.S. Ó Muireadhaigh’s June 1943 note confirming that he had destroyed proofs of ‘the most objectionable parts’ of the book. (NAI)

‘Countryman aged about 50’

Another story is told by a ‘Countryman aged about 50’. He met his future wife B. when visiting her family with his friend M. Invited by B. to go outside with her sister to milk cows, he recalled that ‘I handled B. at once and left her down on a barth of hay in the cabin … A. went milking her cows and I went on deck and stopped there until satisfied. I came away home then, and I was afraid for some time after that I would be called “dada”. She liked me so well and she said that I was such a fine boy that she wouldn’t stop for standing till the match was made. I got £300. That was a dear riding for me.’ Their love-making continued unabated prior to the formalities, much to the vexation of the priest, who said it was a shame. The countryman replied, ‘What was the shame? Wouldn’t any time do (for marriage)?’ B. gave birth to a boy, followed by three miscarriages, the premature death of an infant and another miscarriage. He told the anthropologists that sometime later he brought his wife to the priest ‘to get leave to do it again, so I am doing it away with her now, up and down, up and down, dead or alive, she might do it at last’.

Other excisions concern the sexual attitudes, knowledge, actions and practices of men and women, young and old, married and single. Country people’s comparisons of animal to human procreation, the effectiveness of religious and social censure on illegitimacy, the nature of celibacy and unmarried women’s sexual desire, the telling of humorous sexual stories and references to a prior time of a more lenient atmosphere for courtship and sexual relations were all excised from the chapter on ‘Sex and Familism’. These stories and informants’ ideals of feminine beauty based on ‘big bones, breadth of hip, and robust, fecund strength’ prompted the anthropologists’ observation of the sex act as ‘a rough and tumble trial of strength and potency in which a woman should “be well able for the men”’, but this too was excised. Male and female ignorance of women’s reproductive cycle was also omitted, as was a woman’s story of her fright when she had her first period. She had to explain the sex act to her husband, ‘how it was done’. ‘My man didn’t know about it. He thought to breed as a cow.’ Arensberg removed references such as ‘Joking about the “hardening” of a young wife’ and men’s stories of ‘“knocking good nights” or “gets” out of one’s woman’. The anthropologists opined that adjustments to the ‘violence of love’ were soon made. Admitting that their evidence was meagre, they nonetheless claimed that ‘there seemed to be little necessity for sympathizing with the “brutalized” women of this old-fashioned sex ideology’.

An old man’s verbatim story of the sexual leniency of the past compared to the strictures of the present was also omitted. The man’s colloquial account was explicit in relation to the frequency and prowess of men’s procreative and sexual activity outside marriage. Colloquial language, phrases and metaphors permeate the rich verbatim accounts, which, had they remained, might have informed a broader debate on the sexual lives of the Irish, then and now.

Conclusion

Arensberg and Kimball were the first American anthropologists, but certainly not the last, to get into trouble over sex in Ireland. Decades later, both John Messenger’s study of Inisheer in the 1960s and Nancy Scheper-Hughes in Brandon in the 1970s, for example, caused upset with their description of how sexually naïve, puritanical and repressed the Irish were. In the case of Arensberg and Kimball, it seems that their description of sexual desire amongst Irish country men and women, married and single, gave rise to ‘misunderstanding and resentment’, whereas later ethnographies gave rise to resentment because of their depiction of the Irish as ignorant and dysfunctional. Arensberg and Kimball wrote much about ‘the depth of Catholic attitudes’ towards sex in Family and community, but the deleted sections suggest a more nuanced picture. While ignorance, naivety and innocence of aspects of sexuality, pregnancy and birth permeate the unpublished account, sexual pleasure, desire and sensuality are also evident, as is the public expression of ribald sexual humour. Political expediency and perhaps some uncertainty about the reception of these stories of sex and desire resulted in the suppression of the unconstrained firsthand accounts, part of our legacy of silence about sex in Ireland.

Anne Byrne is Acting Head of the School of Political Science and Sociology, NUI Galway; Eoin O’Sullivan is Professor of Social Policy in the School of Social Work and Social Policy, Trinity College, Dublin.

FURTHER READING

C.M. Arensberg & S.T. Kimball, Family and community in Ireland (Harvard, 1940; 1968).

A. Byrne & E. O’Sullivan, ‘Arensberg, Kimball and de Valera: a story of sex and censorship’, Irish Journal of Sociology (2019).

A. Byrne, R. Edmondson & T. Varley, ‘Arensberg and Kimball and anthropological research in Ireland: introduction to the third edition’, in C.M. Arensberg & S.T. Kimball, Family and community in Ireland (Ennis, 2001).

M. Carew, The quest for the Celtic Celt: the Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland, 1932–1936 (Newbridge, 2018).