‘Dashing waves and dreadful cliffs’: John Lee’s visit to the Blaskets, 1806

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2016), Volume 24WEATHER AND DANGER WERE KEY TO LEE’S EXPERIENCE

By Angela Byrne

At midday on Monday 3 November 1806, John Lee (né Fiott, 1783–1866) left the inn at Dingle on foot for Ventry. It had rained all morning but cleared at noon. Lee had been walking almost every day since 31 July 1806, when he left the Whitehorse Cellar in London to begin a pedestrian tour of England, Wales and Ireland. He had just obtained a BA from St John’s College, University of Cambridge, and his correspondence indicates that his walking tour was inspired by Romantic ideals of solitary enjoyment of the domestic picturesque and sublime landscapes offered by Wales and Ireland. The ongoing Napoleonic Wars made a ‘home tour’ of Britain and Ireland a natural choice for the young gentleman traveller, and Lee was fascinated by the recent Irish rebellions of 1798 and 1803, recording testimony from participants on both sides in his diaries. His journey is detailed in five diaries and three sketch-books held in St John’s College, Cambridge.

Although he mostly travelled alone, at points during his journey Lee found companions who provided him with local information and useful introductions. His companion on the Dingle Peninsula was Coffy, an innkeeper from Kenmare. Lee’s visit to the Blaskets may have been at Coffy’s suggestion, or may have been inspired by an account of the islands such as that published by the Waterford topographer and writer Charles Smith in his Ancient and present state of the county of Kerry.

Reaching Ventry strand, Coffy told Lee about the summer horse-races that took place there. They continued their walk across Slea Head and along the foot of Mount Eagle (Sliabh an Iolair), looking over the ‘most fine Mountain scene’ and low hills to Smerwick Harbour and to Mount Brandon (Cnoc Bréanainn). Lee thought that the scattered settlements of cabins throughout the landscape ‘add[ed] very much to the general mountain scenery and . . . serve as marks to shew the height up the mountain’. Ascending the road at Glanmore, Lee caught his first view of ‘the great object of our search’—the Blasket Islands. There they paused, ‘to breathe and to look around, and to satisfy or to glut our eyes with the view’. From here, Lee made his first sketch of the Blaskets. Descending the road towards Dunquin (Dún Chaoin), they made a picnic of cold meat, whiskey and clear spring water while admiring ‘the fine scenery of the highly cultivated mountains and the scattered cabins, the sea, the islands and the white waves dashing over the reef of rock’.

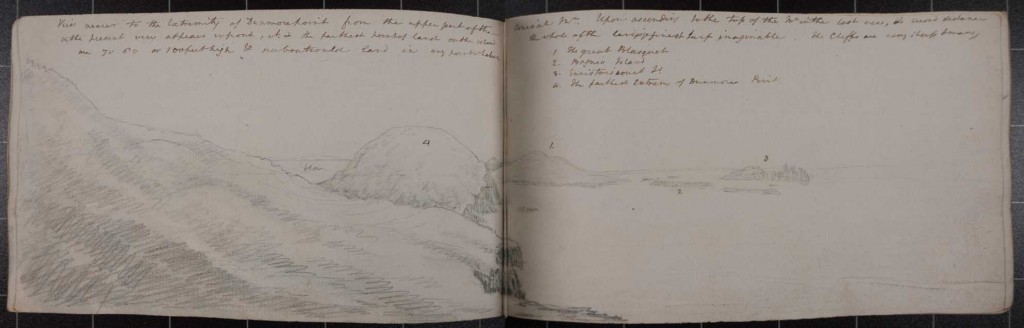

That evening, Lee and Coffy were ‘very hospitably entertained’ at the farmhouse of one Mr Neagle of Dunquin. The following day, Neagle’s son brought Lee and Coffy shooting at Dunmore Head—Lee noted, significantly, that this was ‘the most westerly point of land that we could go to’, satisfied that his excursion had brought him to a remote, rarely visited location. They cautiously scrambled over the rocky outcrop as far as they safely could, watching the waves breaking over the inaccessible Leur (Liúir) chain of rocks petering out into the Atlantic. They stayed two hours, viewing the Blaskets, Valentia and the Skelligs, shooting wildfowl—redshank, cormorants and seagulls—and making sketches. Lee’s sketches are simple, but his detailed annotations provide additional insight into his experiences. On one sketch his notes again emphasise the danger of visiting this remote site:

‘The sea frequently washes over the greatest part of these rocks . . . It was necessary to retreat from the spot where I stood at the approach of every wave.’

John Lee’s 1806 sketch of the Blasket Islands. (St John’s College, Cambridge)

His diary tells us that the weather was mixed sunshine and showers, clear enough to see the Skelligs in the distance but too rough to make the crossing to the Blaskets. They were ‘again hospitably entertained’ at Mr Neagle’s that night, where they stayed up until 3am singing, playing backgammon and drinking whiskey, for which they had sent to Dingle.

It rained all the night of 4–5 November, but Lee woke on the morning of the 5th to find the weather ‘calm and clear’. The boat departed from Dunquin, where the cliffs are ‘actually perpendicular and the one at the landing place is 25 fathoms high’, with a winding road to the shore made for horses to transport cartloads of seaweed for fertilising the land. Lee thought that the cliff looked ‘most dreadful from below and seems to threaten instant destruction on any one who dares to look up at it’. He and Coffy boarded the boat with several labourers; in all, thirteen men made the crossing to Beginish, the nearest of the Blaskets, that morning. They jumped ashore the uninhabited island one by one, spending a little time walking and shooting cormorants. They then proceeded to the Great Blasket, experiencing some difficulty in landing owing to rising wind. Lee admired the method devised by the islanders for securing the thatch to their cottages, weighting down with stones the interwoven bands of straw criss-crossing the thatch. He also saw the new signal tower, erected in response to Napoleon’s campaign. Lee noted with some regret that the weather was ‘too precarious’ to allow them to stay overnight on the Great Blasket, and the rising wind obliged them to hurry back to the mainland. Before departing, they dined on potatoes, milk, whiskey and ‘a certain kind of fowl . . . called in Irish fahirs [foracha, guillemot] which are the young ones before they leave the nests’. Lee describes how the birds were caught using ferrets, and how the fatty young birds were salted and broiled for eating. In Lee’s opinion, the islanders ‘live better than any [person] in Kerry’, enjoying plenty of turbot, hake, rabbits and seafowl. When Lee and Coffy returned to the mainland at 5pm, they set out for Dingle once more, where they arrived at 8pm, having walked through a ‘violent storm of wind and rain’. En route, they passed by ‘Ty-Vorney Geerane, or Mary Geerane’s House’, mentioned in many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century accounts of travels in Ireland as a curiosity and a place of hospitality, cut into the foot of Mount Eagle.

Weather and danger were key to Lee’s experience of the Dingle Peninsula and the Blaskets. Neagle informed Lee of the risks in crossing Blasket Sound; he himself had been stranded several times, on one occasion for twelve days over the Christmas period. Lee found the return crossing ‘very wet and uncomfortable from the high sea’, and he was informed that wrecks were common in the area, with a find the previous week of a ‘piece of a cabin and doors, and . . . a piece of mahogany 16½ long and 20 inches square’. The risk in crossing Blasket Sound, and dread stories of former wrecks, added to the sublime character of the spot. The ‘great object’ of Lee’s ‘search’ emerges not as the Blasket Islands themselves but as the experience of the wild, winter Atlantic and the sublime cliff faces of west Kerry.

Angela Byrne lectures in history at the University of Greenwich.

Read More:

Background

Further reading

A. Byrne, A scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour: John Lee in England, Wales and Ireland, 1806–07 (Farnham, forthcoming).

C.J. Woods, Travellers’ accounts as source material (Dublin, 2009).