Creative women of Ireland: artists and writers from the archives

Published in Issue 4 (July/August 2020), Reviews, Volume 28Royal Irish Academy

https://www.ria.ie/online-exhibition-creative-women-ireland-artists-and-writers-archives

By Tony Canavan

Above: Belfast and Dublin Naturalists’ Field Club taking tea at Slieve Glah, Co. Cavan, July 1896. Naturalist Robert Lloyd Praeger is standing to the left of the table, while his sister, Sophia Rosamond Praeger, is sitting in front.

The COVID-19 crisis presents challenges to cultural institutions, as they have had to close their doors to the public and operate with a skeleton staff (if at all). Many of these institutions have responded by mounting exhibitions on-line or publicising the material already on-line. While this is welcome, an on-line exhibition can be a challenge for the public. Assuming that you have access to the internet, viewing an exhibition on your screen cannot provide the same experience as physically being there. Obviously, viewing a three-dimensional object via the internet is not the same as standing before it and being able to move 360 degrees around it, no matter how good the graphics. In addition, just the experience of being at an exhibition—the atmosphere, the other visitors and the sense of occasion—is absent if one is ‘touring’ the exhibition on screen.

Museum Eye has risen to the challenge and, until our museums open again, will be making virtual visits to these institutions on-line. As this is a new experience for us all (well, for most of us), I took a simple exhibition first. The Royal Irish Academy (RIA) regularly stages exhibitions, which, while interesting, are not necessarily visually impressive; nor do they usually feature hi-tech wizardry. How could they transfer this successfully to an on-line format?

Creative women of Ireland was to open to the public in March and run until December 2020. This had to be abandoned owing to the coronavirus. I thought it worth looking at, as women historically have not featured prominently in the RIA and the variety of creative types—from little-known artists to well-established writers—offered a variety of material to consider. The six women highlighted are Sophia Rosamond Praeger, Eileen Barnes, Mary Fitzpatrick, Mia Cranwill, Lady Sydney Morgan and Katharine Tynan.

Above: Mia Cranwill’s Senate Casket, commissioned by Alice Stopford Green, a magnificent example of Celtic Revival design.

The format is to feature text with illustrations. These range from books and photographs featuring the women to paintings and sculptures. This probably allows for more textual information than one might see at a physical exhibition, where the text is usually limited to panels and captions in display cabinets. I felt obliged to read the text more closely than if visiting the exhibition in person, where, I have to confess, I am more inclined to let the exhibits speak for themselves rather than read explanations and expositions provided by a curator.

That said, I did enjoy this exhibition. Scrolling down the screen was an effortless exercise, and going back to check what was said or to view an exhibit again did not necessitate actual walking, as in a museum. I did learn a lot and enjoyed looking at the illustrations. Some were clearer than others, although this was due to the quality of the original image. Others, particularly illustrations from books or reproductions of paintings, were really clear and the colours vivid. Perhaps it was just a psychological trick, but these seemed even clearer and more vivid than they would in reality. Of course, problems like glare or shadows are automatically absent from scanned images on-line.

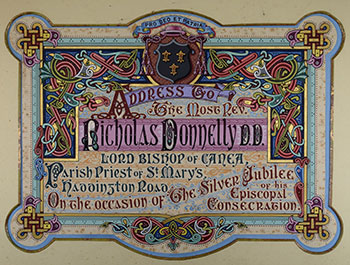

Above: A 1908 illuminated address by Mary Fitzpatrick to Revd Nicholas Donnelly DD, lord bishop of Canea, parish priest of St Mary’s, Haddington Road, Dublin, on the occasion of the silver jubilee of his episcopal consecration.

The women themselves ranged from the interesting to the fascinating. Sophia Rosamond Praeger was a polymath: a sculptor, illustrator, botanical artist and poet. She studied art in Belfast and at the Slade School of Art, London, winning prizes and scholarships. In 1892 she spent time in Paris before returning to Ireland, where she set up a studio and became an artist. She exhibited in Dublin, Belfast, London, Paris and Brussels. She was a member of the Guild of Irish Art Workers, an honorary member of the Royal Hibernian Academy and president of the Royal Ulster Academy (1941–3). As well as all this, Praeger was an advocate for women’s rights and a voice for women artists in Ireland. She illustrated cards and posters for suffrage groups in Ireland and England. Her story is told alongside anecdotes and illustrations of her work, such as her book The young stamp collectors.

Above: The young stamp collectors by Sophia Rosamond Praeger.

Another woman with a fascinating life was Mia Cranwill. She was born at Drumcondra, Dublin, in 1880, the daughter of Arthur Cranwill, an analytic chemist and ardent Parnellite. Around 1895 the family moved to Manchester, where Mia attended the Manchester School of Art, qualifying as a teacher. She gave up teaching, however, to pursue a career in the arts, particularly metalwork. She returned to Dublin in 1917 and designed and produced jewelry using Celtic motifs at her Suffolk Street studio. During the War of Independence she stored guns there for the IRA. Her finest achievement is the Senate Casket, commissioned in 1924 by historian and senator Alice Stopford Green (1847–1929) for the Irish Free State Senate. Stopford Green intended that the casket should hold a vellum roll containing the signatures of senators and sit on the chairman’s desk in the chamber. It’s a magnificent example of Celtic Revival design.

I enjoyed my trawl through this exhibition and recommend it to anyone with time on their hands during the restrictions. Another advantage of being on-line is that you can view it from the comfort of your armchair and return to the exhibition at any time.

Tony Canavan is the editor of Books Ireland.