Creative Centenaries #Making History 1916

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2016), Reviews, Volume 24Ulster Museum, Botanic Gardens, Belfast

Creativecentenaries.org

By Tony Canavan

The Ulster Museum is to be congratulated for its imaginative approach to 1916. With so many commemorative exhibitions, it is difficult to find a new way to approach the centenary. This exhibition is part of a larger initiative in Northern Ireland promoting a creative response to the anniversaries of the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme.

Above: The still relatively new medium of film was used to tell the story of battles in France and the Easter Rising, which also featured in news footage of the day.

The exhibition engages with creativity itself, exploring just how the First World War, and to a lesser extent the Easter Rising, encouraged innovation and invention in different spheres. In the museum’s Art Zone, rather than the history galleries, it features display panels, artefacts, documents and interactive installations. There are some contemporary art installations on the theme of war and violence, but I did not think that they added much. The exhibition is organised thematically, looking at popular entertainment, the home front, recruitment, the role of women and so on.

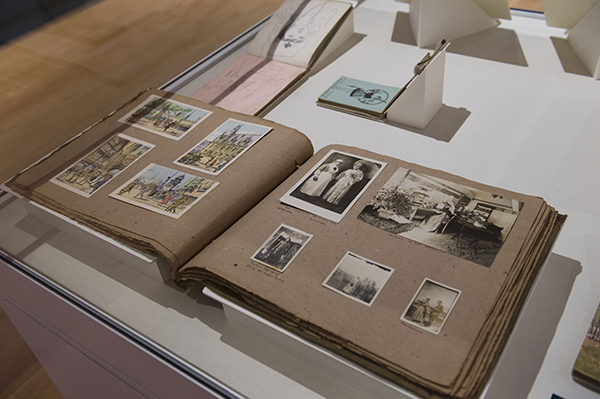

Above: Reflections on the actual experience of war are conveyed through the letters and diaries of those involved, as well as drawings, photographs and film.

The section on music and song shows how popular entertainment, such as music hall and theatre, was used to promote the British war effort and the Republican cause. Sets of earphones enable you to listen to songs from both sides. Attention is also given to how members of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, such as Arthur Shields, took part in the 1916 Rising. Even recruitment rallies incorporated a concert by a military band.

Children’s games were influenced by the First World War. Two such games, ‘Bombarding the Zeppelins’ and ‘The New Game of Jutland’, are featured, with the latter complemented by a modern video game devised by the students of Bangor Grammar School. Elsewhere on the home front, propaganda posters encouraged thrift and various means by which food and other materials could be made to go further.

One innovation brought about by the necessities of war was the recruitment of women into the workforce. The ‘Munitionettes’ puts the spotlight on the women in Belfast and Dublin who worked in factories manufacturing munitions. The National Shell Factory was based in Dublin and the photographs of the women there present a cheery picture of happy workers, with no hint of the hardship and dangers involved. In fact, Irishwomen worked in factories throughout Britain and many died in the frequent accidents that occurred. Women also played a part on the military side, as nurses or in providing catering for off-duty soldiers.

Turning to the Rising, the exhibition illustrates how women featured prominently in this, and not just as nurses or messengers but also as opinion-formers, fighters and commanders. Countess Markievicz inevitably gets a mention, but attention is given to other women too, notably Belfast-born Winifred Carney, who was an aide to James Connolly. She and VC winner William McFadzean feature in the exhibition’s complementary graphic storybook.

Above: ‘Armoured Pram for Derry’ by Eamon O’Doherty, one of several contemporary art installations on the theme of war and violence. On the wall behind are panels on the ‘Munitionettes’, women employed in munitions manufacture.

Many established artists were responsible for posters encouraging men to enlist. Those directed at Irishmen are on display here, from the famous ‘I’ll go too’ poster to the sinking of the Lusitania. Enlistment was encouraged by various means—from appealing to the fighting Irish spirit to shame (women being encouraged to brand as a coward a boyfriend or husband who did not enlist). This is complemented by a display of Republican propaganda urging support for an independent Ireland and venerating those executed in the aftermath of the Rising.

Many Irish newspapers, and English ones available in Ireland, such as the Daily Mirror, Daily Sketch and Sunday Herald, carried accounts of the war glorifying ‘our boys’ and vilifying the Germans. Such efforts displayed creativity of a different kind in the form of inventing stories of Allied heroism and German atrocities. The still relatively new medium of film was used to tell the story of battles in France and the Easter Rising, which also featured in news footage of the day.

The section headed ‘Making New’ concentrates on the industrial and technological innovations brought about by the war. On the home front, production in factories and farms was radically transformed to facilitate quantity and speed. New machines and production methods emerged in response to the demands of war. On the military side, the war saw rapid development not only in weapons, like machine-guns and tanks, but also in flight, transport and wireless communications. These innovations were to have benefits for civil society.

Lest you think that this exhibition presents an unwarranted positive spin on war and civil unrest, the final section reminds us that war is hell. Reflections on the actual experience of war are conveyed through the letters and diaries of those involved, as well as drawings, photographs and film. The text here reminds us that war was a terrible experience for those who went through it and that they often found it hard to articulate their emotions and memories.

This is a good exhibition that takes an idea and elaborates on it. While other commemorations have been full of pomp and pondering, this one makes us take a fresh look at these conflicts involving Ireland, and reminds us that the First World War and the Easter Rising affected not just politics but also society, culture and industry.

Tony Canavan is editor of Books Ireland.