The Colt Wood railway incident

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2016), Volume 24MY FAMILY HAS A SPECIAL LINK WITH 1916: MY GREAT-GRAND UNCLE PADDY FIRED THE FIRST SHOT IN THE EASTER RISING

By Adam Murphy

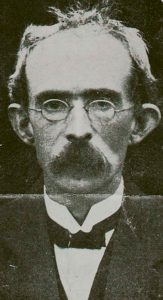

My great-grand uncle was Patrick Joseph Ramsbottom, known to his family as ‘Paddy’ and to his comrades as an fear mór because he was over 6ft tall. He was born on 21 May 1891, the eldest son of Edward and Margaret Ramsbottom. His siblings were James (b. 1892), Margaret (b. 1893), Norah (b. 1897), Henry (b. 1899), Edward (b. 1901) and Kate (b. 1906).

Above: Tom Clarke—in 1914 he asked Paddy Ramsbottom to organise the IRB in County Laois. (NLI)

Records from the census of 1901 show that Paddy lived with his family in Maryborough (now Portlaoise). In 1906 he joined Sinn Féin and the Gaelic League. The 1911 census shows that Paddy was then living in Athlone, Co. Westmeath, having moved there in 1910. He worked as a shop assistant for the Prior family and continued his involvement with the republican movement, joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Athlone and organising a branch of Na Fianna Éireann. Just as the First World War broke out, Paddy left Athlone and moved to Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) in 1914. It was at this stage that he joined ‘B’ company, 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade, Irish Volunteers.

His life up to 1916

My great-grand uncle’s involvement in the Easter Rising began before 1916. In October 1914 Paddy returned to his home in Portlaoise. At this time there were only about a dozen Irish Volunteers in the whole county. Tom Clarke asked Paddy to meet with him and to organise the IRB in County Laois. Tom gave him the authority to enrol and swear in new members and expected that only men with ‘proper national outlook’ would be enrolled.

On 17 October 1914 Paddy held a meeting in Portlaoise to establish the Irish Volunteers. He was elected company captain and had about a dozen members in Portlaoise. In Paddy’s witness statement to the Bureau of Military History 1913–21 (WS 1046) he said:

‘There was a strong pro-British element in Portlaoise at that time, and due to local Parliamentary Party influences it was very difficult to get recruits for the Volunteers under the leadership of MacNeill.’

The company paraded one night per week. These parades/practices included drilling and teaching members how to use bayonets and guns. Between 1914 and Easter 1916, the company got gelignite and fuses from the coal mines of Wolfhill. These were brought to Dublin and given to Volunteer headquarters. Fund-raising events were also organised: an Aeridheacht (a kind of open-air day of entertainment) was organised in Portlaoise in September 1915 to help buy arms. During 1915, members of the Irish Volunteers visited the Portlaoise company. In the autumn of 1915 members of the company attended a lecture in the headquarters of the Irish Volunteers in Dublin, where they heard a lecture about demolishing a railway. The Laois company marched at the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa as well.

The lead-up to the Rising

In January 1916, Piaras Béaslaí and Lt Eamon O’Kelly addressed a company meeting and spoke about the urgent need for more intensive training owing to the impending rising. A meeting of the Portlaoise company on Sunday 16 April 1916 was informed that a rising would definitely take place, and the date and details of the company’s duties. After this meeting Paddy was told that it had been decided to rise at 7pm on Easter Sunday, 23 April. Duties assigned to the Portlaoise company included the demolition of a railway line from Waterford to Dublin with ‘the object of holding up and delaying the advance of enemy troops that might be sent to Dublin from Britain via Rosslare or Waterford’. Plans were made to cut the Waterford–Portlaoise line at Colt Wood, between Portlaoise and Abbeyleix. (It was also decided to cut the Kilkenny–Kildare section of the line, but no exact location was decided upon and in the event this line was never cut.) When this had been done, the company was to go to the Scallop Gap, near Borris, Co. Carlow, and await further orders.

Above: One of the three plaques on the monument (designed by Robert Ballagh) commemorating the Colt Wood derailment. The others are a copy of the Proclamation and a dedication that names the Volunteers involved, including Paddy Ramsbottom.

Colt Wood

Before Easter Sunday night Colm Houlihan, who worked for the Great Southern and Western Railway Company, took a number of tools from the workshop. Paddy took charge of six members of the Portlaoise company that night—Laurence Brady, Thomas F. Brady, John Muldowney, Patrick Muldowney, Michael Sheridan and Colm Houlihan.

At 7pm sharp they made their way to Colt Wood and began their work. They used the tools that Colm Houlihan had given them and cut down telegraph lines and telegraphy wires. They also removed several lengths of rail and some sleepers. While they were doing this, three local girls, the Sheerans and a Miss Whelan, passed by and were taken prisoner until the work was completed. They were then brought to their homes and warned not to go out again that night or to give any information to anyone about what they had seen.

Once the job was finished, the company took shelter in Colt Wood close to the railway. The railway company sent one of their workers, William Dalton, to investigate the signal failure on the line. As he moved closer to where Paddy and the other members of the Portlaoise company were hiding, my great-grand uncle called out to him to halt. Dalton did not obey, so Paddy fired over the railway worker’s head. This was, as Paddy said, ‘in all probability the first shot fired in the Rising’.

Dalton extinguished his lamp and escaped into the darkness without injury. Soon after the Volunteers had left the wood, he returned with five colleagues and four policemen. A train approached the site; it was derailed and crashed onto its side as it passed over the demolished section of the track. The engine driver and the fireman were flung from the cabin of the engine but nobody was seriously injured.

What happened after the event?

The Laois Volunteers were delighted with their success and made their way back to a ‘safe house’, Brady’s in Lalor’s Mills, where they stayed for several days. The Brady sisters (Kathleen, May, Noreen and Breda) took care of them while they were on the run. When they heard that the Rising in Dublin had failed, the group split up. Many of them later went on to take part in the War of Independence and the Civil War.

The rest of the Laois company had tried in vain to contact the Carlow/Kilkenny Volunteers, and for the next couple of days they kept trying to find out what was happening. At the Easter Saturday meeting they had been told not to believe misleading newspaper reports, so the company stayed together, hoping that the Rising would spread throughout the country. On Monday 1 May, Eamonn Fleming went to Dublin and found out that all the leaders had been captured. He returned to Dublin with my great-grand uncle and they were told by Fr Augustine that the Rising was definitely over. They stayed at Fr Costello’s house that night because of the military presence, but they went home the next morning.

Father J.J. Carney from Portlaoise asked them to surrender to the RIC county inspector in Portlaoise, but they refused and decided to go on the run:

‘We dumped our guns at Brady’s farm. While on the run I kept in touch with the other men . . . I remained on the run for about eleven months during which time I collected gelignite and detonators.’

When he came off the run, Paddy organised companies of Volunteers and, after speaking with Michael Collins, amalgamated these companies into a battalion. Paddy was made battalion commandant of the Laois Brigade. He became an armed escort for Kevin O’Higgins TD, who was visiting Laois to collect money for the Dáil Loan. Laois was to account for the largest amount subscribed in any county in Leinster with the exception of Dublin. Paddy brought the money to Dublin on his bicycle in a bag!

‘There were numerous raids for me in different parts of the county but I never left my area except on duty.’

A report published in the Nationalist and Leinster Times, dated 28 October 1918, shows an application from the rail company for compensation on account of the derailing in the Queen’s County quarter sessions:

‘ECHO OF EASTER WEEK

Derailing of engine and carriage. His Honour Judge Fitzgerald continued the business of the quarter sessions at Maryborough on Monday. The GSWR Company applied for £328-9s-6d compensation for the alleged malicious destruction of 60 yards of the permanent way, twelve 30-ft. rails, 66 sleepers, 208 bolts and one locomotive engine and one bogey brake carriage early in the morning of the 24th April last on the lands of Clonadadoran.’

Paddy’s life after the Rising

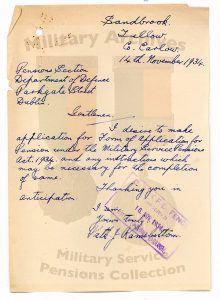

Paddy was arrested in November 1920 and interned successively in the Curragh Camp, Arbour Hill and finally Ballykinlar, Co. Down, from where he was released in December 1921. He joined the Gardaí in 1927 and was stationed in Duncannon, Co. Wexford, Carlow and the Phoenix Park. After he left the Gardaí, he got a job in the Department of Education. In November 1953 he was successful in his appeal for a military service pension, after he had been refused in 1941. I discovered during my research that he lived in Sandbrook near Ballon, Co. Carlow. My family and I lived in Ballon up to two years ago and our house would have been about two miles away from his. While he was living in Sandbrook he made his first pension application in 1934. Through John Kehoe of Tullow Museum, who contacted one of the oldest residents in the area, Mr Keppel in Rathrush, who is about 85 years old, we found out that the connection was actually to Sandbrook House. During the Civil War, local IRA units burned many of the ‘big houses’ in the area. When it was vacant, it was taken over and used as a boarding house for newly appointed Civic Guards stationed in County Carlow. Paddy was one of these men. When he reapplied for his pension in 1942, he was living at Black Horse Avenue, Dublin. It would seem likely that he lived in Ballon when he was stationed in Carlow and in Black Horse Avenue when he worked in the Phoenix Park. He married Brigid Concanon (known as ‘Daisy’) but they had no children. Paddy died in March 1965 and is buried in Portlaoise, Co. Laois. Daisy died on 3 March 1971.

Paddy was arrested in November 1920 and interned successively in the Curragh Camp, Arbour Hill and finally Ballykinlar, Co. Down, from where he was released in December 1921. He joined the Gardaí in 1927 and was stationed in Duncannon, Co. Wexford, Carlow and the Phoenix Park. After he left the Gardaí, he got a job in the Department of Education. In November 1953 he was successful in his appeal for a military service pension, after he had been refused in 1941. I discovered during my research that he lived in Sandbrook near Ballon, Co. Carlow. My family and I lived in Ballon up to two years ago and our house would have been about two miles away from his. While he was living in Sandbrook he made his first pension application in 1934. Through John Kehoe of Tullow Museum, who contacted one of the oldest residents in the area, Mr Keppel in Rathrush, who is about 85 years old, we found out that the connection was actually to Sandbrook House. During the Civil War, local IRA units burned many of the ‘big houses’ in the area. When it was vacant, it was taken over and used as a boarding house for newly appointed Civic Guards stationed in County Carlow. Paddy was one of these men. When he reapplied for his pension in 1942, he was living at Black Horse Avenue, Dublin. It would seem likely that he lived in Ballon when he was stationed in Carlow and in Black Horse Avenue when he worked in the Phoenix Park. He married Brigid Concanon (known as ‘Daisy’) but they had no children. Paddy died in March 1965 and is buried in Portlaoise, Co. Laois. Daisy died on 3 March 1971.

Adam Murphy is a fifth class pupil in Gaelscoil Eoghain Uí Thuairisc, Co. Carlow.

Read More:

Decade of Centenaries all-island schools’ history competition 2017

How I am connected to Patrick J. Ramsbottom

FURTHER READING

E. Cody, http://www.storiesfrom1916.com/1916-easter-rising/the-first-shot/.

J. & B. Fleming (eds), 1916 in Laois (Laois 1916 Commemoration Committee, 1996).

L. Ó Duibhir, Prisoners of war: Ballykinlar internment camp 1920–1921 (Cork, 2013).