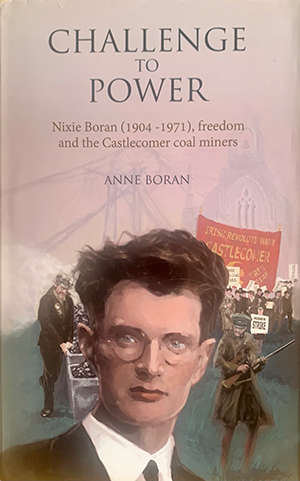

CHALLENGE TO POWER: NIXIE BORAN (1904–1971), FREEDOM AND THE CASTLECOMER COAL MINERS

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 3 (May/June 2022), Reviews, Volume 30 ANNE BORAN

ANNE BORAN

Geography Publications

€35

ISBN 9780906602973

Reviewed by John Cunningham

John Cunningham lectures in History at NUI Galway.

The subject of this biography was a mineworker and union leader in Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny. It is written by his daughter, who brings scholarly insights to the task drawn from a working life as a sociologist, as well as an understanding of the local society and a deep knowledge of the family background.

In 1930, Nicholas ‘Nixie’ Boran was impressed by what he saw of coalmining in the Donetsk basin, which he visited after attending a union gathering in Moscow. In a letter published in the Kilkenny Journal on his return, he compared local conditions with those on the borderlands of Ukraine and Russia. The Donetsk miner worked a six-hour day, his working clothes were routinely laundered, and he had a hot bath and a hot meal waiting at the end of his shift. By contrast with Castlecomer, where miners’ wives were worn out with cooking and washing filthy clothes, in the Donetsk ‘the woman is emancipated and is not regarded as the inferior or a slave of men’ (p. 83). Determined to raise conditions in Ireland to the level he believed was prevalent in the Soviet Union, Nixie threw himself into militant activism. Already a leader of the Revolutionary Workers’ Groups (RWG), a proto-Communist Party, he established an Irish Mine and Quarry Workers’ Union (IMQWU) in Castlecomer. He would also join the executive of Saor Éire, a radical political adjunct to the IRA.

Aged 26 when he visited Moscow, Nixie had already seen a lot of life. From a family that had subsisted for generations on mining and a few acres of land, he went down the mines himself in 1918, aged fourteen. He had considered a religious vocation, and his biographer suggests that his two years in a De La Salle junior seminary were important educationally and perhaps to the development of leadership qualities. This was a turbulent time, when a spirit of revolution affected social and political life in intersecting and overlapping ways. In Castlecomer, miners came into conflict with the mine-owner Prior-Wandesforde (of the hereditary local landed family), forming a branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), with some joining the IRA. Unemployed as a result of disputes in the coalfield, Nixie joined the Free State army on the eve of the Civil War. Soon disillusioned, he deserted to the anti-Treaty IRA, bringing weapons with him. Though captured more than once and sentenced to death, he came through with an intact fighting spirit, maintaining contact with left-wing republicans through periods in Dublin and while working in mines in Scotland and Wales.

Back in Castlecomer, Nixie was able to build the IMQWU and, when the mine-owner ignored its claims on pay and conditions, a strike involving 400 men broke out in October 1932. There was no strike pay and little support from other unions, because the IMQWU was affiliated to the Red International of Labour Unions rather than the Irish Trade Union Congress. Nevertheless, in a battle with Prior-Wandesforde there was inevitably some local support for the miners, including from shopkeepers, who evidently assisted financially and prevailed upon constituency TDs to intervene as arbitrators. A settlement was reached at the end of six weeks, which the IMQWU was able to represent as a victory to the considerable chagrin of local enemies, secular and religious.

In the context of a wider ‘red scare’—which resulted inter alia in the deportation from Ireland of Leitrim RWG leader Jim Gralton—the atmosphere in Castlecomer was tense in the aftermath of the strike. The bishop of Ossory came to preach, accusing IMQWU leaders of speaking with the ‘voice of the devil’, and obliging his congregation to join a ritualised renunciation of the devil. Thus commenced a sustained campaign, which placed enormous pressure on individual miners to leave the union. Ultimately, Nixie and his comrades opted to retreat, and in late 1933 they dissolved the IMQWU and joined the ITGWU. Politically Nixie was moving away from communism and republicanism and towards the Labour Party, later reflecting ruefully that he had tried to take on too much. Space precludes adequate treatment of the following three and a half decades, during which Nixie Boran remained prominent as a trade union advocate for the health and welfare of miners through the decline of their industry. And there would be other strikes in the Castlecomer mines, including an eleven-month marathon in 1949–50.

With Challenge to power, Anne Boran pays a fine tribute to her father, tracing his political odyssey from the socialist republican milieu of the 1920s and 1930s, while considering his motivations. The book is valuable for its contextualisation of a remarkable life story, treating the power structures that were challenged by miner solidarity, and exposing the class divisions that led miners to remain loyal to Nixie Boran in the face of threats of excommunication by their clergy.