A ‘Catholic wind’ on Bantry Bay?

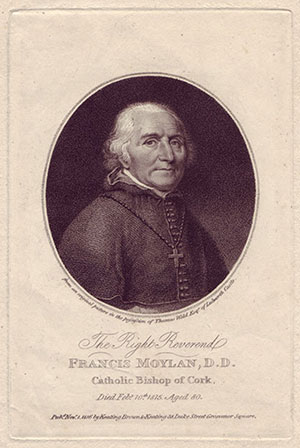

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2017), The United Irishmen, Volume 25The decisive stance taken by the Catholic bishop of Cork, Francis Moylan, towards the threat of French invasion in December 1796.

By Gordon Kennedy

On Christmas Day 1796, while Theobald Wolfe Tone was still anxiously pacing the deck of a French warship, desperately hoping that Lazare Hoche’s subordinates would actually come to a decision and land the depleted force of revolutionary troops that were seeking shelter below decks, the Catholic bishop of Cork, Francis Moylan, delivered a pastoral to his flock. While previous pastorals of the Catholic hierarchy had contained similar pleas to remain loyal and steadfast to king and country, Moylan’s was more vociferous in tone and apparently effective. Furthermore, it could have earned him a severe, and possibly fatal, penalty had the expeditionary force landed in any great numbers.

On Christmas Day 1796, while Theobald Wolfe Tone was still anxiously pacing the deck of a French warship, desperately hoping that Lazare Hoche’s subordinates would actually come to a decision and land the depleted force of revolutionary troops that were seeking shelter below decks, the Catholic bishop of Cork, Francis Moylan, delivered a pastoral to his flock. While previous pastorals of the Catholic hierarchy had contained similar pleas to remain loyal and steadfast to king and country, Moylan’s was more vociferous in tone and apparently effective. Furthermore, it could have earned him a severe, and possibly fatal, penalty had the expeditionary force landed in any great numbers.

Welcomed in loyalist circles

Moylan’s pastoral was widely welcomed in loyalist circles. Robert Day, MP for Tuam, described it as ‘breathing a spirit of peace and loyalty worthy of an apostle’. To him, Moylan had not ‘balanced between duty and danger’ in his swift call to resist the French ‘invader’. To packed Christmas congregations, Moylan urged his Catholic brethren to rally to the king’s standard and to reject the ‘irreparable ruin, desolation and destruction occasioned by French fraternity’. In a grim warning to the people filling the pews, he stated that any ‘contrary conduct will draw inevitable ruin on you here and eternal misery hereafter’. He stated his belief that Catholic emancipation was imminent and that the worst of their distresses were already consigned to history; ‘for blessed be God, we are no longer strangers in our own native land, no longer excluded from the benefits of the happy constitution under which we live, no longer separated by odious distinctions from our fellow subjects’. Regardless of certain expedient inaccuracies, the pastoral seems to have had the desired effect. No signal fires welcomed Hoche’s experienced veterans; there was no rapturous welcome as promised by Tone.

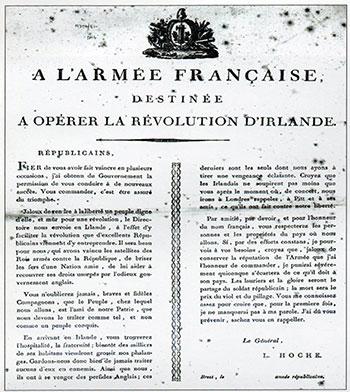

Above: General Lazare Hoche’s December 1796 proclamation to his troops, stressing the need for discipline during the Irish campaign.

Tone’s diary tells us that vicious storms and French indecisiveness were the direct causes of the expedition’s failure. To underestimate the power of hierarchical censure in the immediate context of that December would, however, be unwise and counter-intuitive. As Jeremiah Collins revealed in his funeral oration for Moylan in 1815, the pastoral of 1796 contained a power that ‘inspired the multitude with an order and a prowess to defend their country, their altars and their homes’. Bishop Moylan, in return for his loyal pastoral, received the freedom of Cork city and unanimous praise from politicians and clergy alike. Monsignor Erskine, the papal representative in London, wrote to Moylan, congratulating him on the gallantry he had shown during the attempt by the ‘common enemy to invade’. He also informed him that he was sending a copy of the pastoral to the pope as proof that the ‘spiritual direction of the Catholics of Ireland is committed to such hands as can, and will, preserve them from all contagion’.

The pastoral was not merely a spontaneous warning by Moylan against a lately manifested threat or the means to ingratiate himself into favour. Moylan could speak with some authority on the French revolutionary order, given the fact that he had been educated there and had received explicit (albeit highly partisan) accounts of its excesses from his close friend Abbé Edgeworth, King Louis XVI’s confessor. Moylan passionately believed that religion itself was under threat from revolutionary change and that the people of Ireland were being duped by radical incendiaries into political beliefs that they could neither comprehend nor understand. It was a classic example of the paternalistic instinct with which the Catholic clergy of that time were imbued; the ‘natural’ leaders of the Catholic multitudes needed to scold the wavering and damn the disaffected.

Lord Camden was so impressed with Moylan’s words of loyalty that he suggested that the pastoral should be translated into Irish and circulated around the kingdom in an attempt to defuse potential sedition in the aftermath of the French attempt on Ireland. Privately, the United Irishmen simply dismissed Moylan’s stance as ‘pious fraud’, the rantings of a craven snake-oil salesman. Publicly, however, they had to be mindful of venting their disgust at ‘Castle Catholics’, lest they alienate recruitment into their ranks by espousing Jacobin-style anti-clericalism. Besides, they took heart that the French, having shown serious commitment towards the liberation of Ireland, would return to arm and assist their planned revolution.

Bishop Hussey’s withering response

There were some dissenting voices, however, within the Catholic hierarchy concerning the deferential tone of Moylan’s words. In 1797, Bishop Thomas Hussey from the neighbouring Waterford diocese drew much criticism from his contemporaries when he publicly condemned the proselytising practices of militia officers on their mostly Catholic recruits. A critical letter from Moylan to Hussey brought about a withering response from the Waterford prelate. Hussey reminded Moylan that his 1796 pastoral had produced few concessions from the government on the Catholic question except ‘a declaration that Catholics should wear the remaining chains to the end of the world’. It is not recorded how Moylan reacted to this remark but it can be imagined that it irked the Corkman considerably, given the fact that there were already rumours on the ground that he was in receipt of a Castle pension for his stance in 1796.

Above: A contemporary French cartoon depicting Le Degraisseur Patriote (‘the patriotic de-fattening machine’). Revolutionary images such as this terrified Moylan and the Irish hierarchy.

While Hussey’s complaints garnered support from the laity, the Catholic hierarchy worried that any perceived criticism of Crown forces’ behaviour could undermine and eventually scupper their ongoing appeals for full emancipation. The old formula remained the best avenue for change—loyalty to king and country—and this sat very comfortably on the shoulders of the bishop of Cork. To radicals and revolutionaries, this provided further proof that the hierarchy had indeed been bought off by the Castle with the establishment of Maynooth in 1795. In their eyes, its annual subsidy from government merely confirmed that the clergy were blatantly compromised and thus tightly controlled by the Castle ‘junto’. In Moylan’s eyes, the establishment of the seminary was crucial to the infrastructure of Catholicism in a country emerging from penal persecution. To him, it was a blessing that should ‘excite our gratitude and unshaken loyalty to our gracious sovereign, a sovereign who [had] done more for the Catholic body and this kingdom than any or all of his predecessors’. However obsequious these sentiments may appear today, they were forcefully held by the hierarchical establishment during this period of white-hot smothered rebellion. Loyalty was also a sound tactic of self-preservation. It was far better to trust in gradual Catholic emancipation than in a new revolutionary order established by ‘atheistical incendiaries’.

Less is known about the effect of the 1796 pastoral on the ordinary Catholics of County Cork, but it is notable that it was one of the areas least affected by the rebellion that erupted seventeen months later. The Burkean philosophy that if you had the loyalty of the bishops then you had the loyalty of the people seemed to have paid dividends for the establishment. This was particularly evident in Munster during 1798. Apart from the obvious martial reasons for this apparent apathy, the Castle was very aware that the hierarchy had come good for them in the final showdown. Moylan benefited personally from his loyal exertions during these critical years. He replaced Thomas Hussey as the main intermediary between the Catholic hierarchy and eminent politicians such as Castlereagh, Portland and Pitt. The goodwill and heartfelt loyalty displayed by Moylan during the United Irish crisis was harnessed by Pitt and Cornwallis. They needed him and the rest of the hierarchy to push for Catholic acceptance of a Union that was linked to full emancipation.

Failed politically

On this political issue, however, Francis Moylan was a disappointed man when he died on 10 February 1815. After all the professions of loyalty during the 1790s, the support of various Castle administrations and for the Union itself, the holy grail of emancipation looked as far off as ever as he lay on his deathbed. Moylan the pastor had succeeded spectacularly in the re-emergence of a Catholic infrastructure in Munster, but Moylan the politician had failed in the ultimate goal of guiding his people to full emancipation by peaceful means. That measure did not arrive until 1829, fourteen years after his death. Nevertheless, a sturdy foundation had been laid to build the type of Catholic clerical ascendancy that was so evident in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Gordon Kennedy lectures in Irish history at the Boston University Overseas Programme based in Dublin City University.

FURTHER READING

M. Elliot, Partners in revolution: the United Irishmen and France (Yale, 1982).

D. Keogh, The French disease: the Catholic Church and radicalism in Ireland, 1790–1800 (Dublin, 1993).

J.A. Murphy (ed.), The French are in the bay (Dublin, 1997).