Captain Swayne and the Battle of Prosperous, 24 May 1798

Published in Issue 3 (May/June 2018), News, Volume 26By Fergal Browne

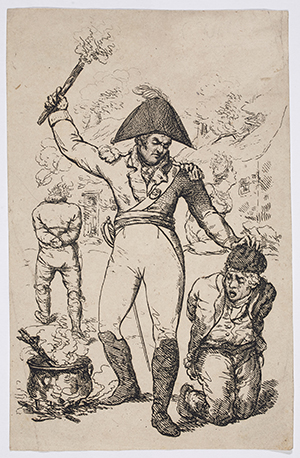

Above: ‘Captain Swayne pitch-capping the people of Prosperous’, as depicted in the Irish Magazine, February 1810. (NLI)

There will be a re-enactment of the fighting between United Irishmen and the Royal Cork City Militia under the command of Captain Richard Swayne, which resulted in the death of Swayne and all of the Corkmen and the burning of their barracks. The well-known Kildare-based re-enactment group ‘Lord Edward’s Own’ will portray the Cork City Militia, with locals supported by several re-enactment groups from other counties, the largest being the ‘Enniscorthy Historical and Re-enactment Society’, acting as United Irishmen. There will also be a pop-up museum in the village displaying artefacts of the period.

On Sunday 20 May 1798, Swayne and a company of Cork City Militia were billeted in the town. Swayne marched to the chapel and, according to some accounts, hurled the priest to the ground and threatened to destroy the building unless weapons were handed in. According to further accounts, a ‘reign of terror’ was then instituted by the militia in Prosperous, with the pitch-cap being in regular use. It was indicated to Swayne by Dr John Esmonde (himself a United Irishman, though unbeknownst to Swayne) that weapons would be delivered to Swayne under cover of darkness on the evening of 24 May. On the night, rather than handing over weapons, the rebels attacked the barracks; most of the militia company were killed and Swayne himself was surprised in bed, shot and piked to death and his body burned in a tar barrel. Even the most loyal accounts of the Rebellion are critical of Swayne. William Hamilton Maxwell, in his History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798, criticises Swayne’s military judgement, going so far as to call it stupidity. He points out that if Swayne had even considered placing a cart across the road in front of the barracks and doubled his pickets, there would have been time to warn and rouse the garrison prior to the attack. Maxwell concludes that Swayne’s death was ignoble and that, despite being killed by the rebels, he was the victim of his own folly.

Swayne is generally known as Richard Longford Swayne, though it is likely that his middle name was in fact ‘Longfield’, as he was descended on his mother’s side from the Longfield family of Castle Mary, near Cloyne. Swayne is portrayed in one of the best-known images of the 1798 rebellion—‘Captain Swayne pitch-capping the people of Prosperous’ (above). He was the son of John Swayne of Youghal, a revenue collector in Cork City, and Elizabeth Uniacke, daughter of a prominent Cork gentry family. There is evidence to suggest that Swayne himself was a merchant in Youghal, and was admitted as a Freeman of the City of Cork before joining the militia in 1793.

Captain Swayne’s eldest brother, General Hugh Swayne, was appointed governor of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, in 1813. While Captain Richard Swayne was described as a ‘zealous Protestant’, it is interesting to note that amongst the correspondence of his brother, kept in the National Archives of Canada, is a letter from one Lawrence Kavanagh, thanking General Swayne for the trust placed in him. Kavanagh was a Roman Catholic, son of emigrants from County Waterford, and General Swayne chose him for the administration of statute labour in connection with road construction in the colony of Cape Breton.

Furthermore, Lawrence Kavanagh would later become the first Catholic to take a seat in a British legislature since the imposition of the Penal Laws in the 1690s. In 1822 the Canadian legislature introduced a law to remove the bar on Catholics sitting in parliament, the first colony in the British Empire to do so. Captain Richard Swayne’s father, John Swayne, is commemorated by a large marble monument in the Collegiate Church of St Mary in Youghal. The monument states that he was a man of exceptional charity and goodwill. In Kildare, however, his son is still remembered for his brutality.

Originally from Cork, Fergal Browne is a local historian now living in Kildare.