The Brook Kerith: ‘George Moore’s blasphemy’

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2016), Volume 24A BOOK THAT GENERATED COLUMNS OF COMMENT IN NEWSPAPERS AND JOURNALS IN LONDON, NEW YORK, PARIS AND ELSEWHERE WAS IGNORED IN IRELAND

By Dennis Kennedy

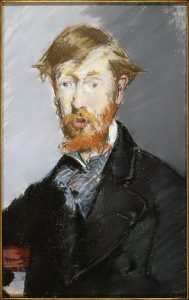

Above: Portrait of George Moore by Édouard Manet, 1879. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY)

One hundred years ago, on 7 September 1916, the London Times carried a short report of a case at the Bow Street magistrates’ court. The court had been asked to issue a summons for blasphemy against the author and publishers of the book entitled The Brook Kerith. The applicant was Lord Alfred Douglas—‘Bosie’ of Oscar Wilde fame—and the defendant was George Moore, owner of Moore Hall and its estate in County Mayo and one of the most successful authors in these islands, dubbed by some ‘the English Zola’ and by others ‘the Irish Turgenyev’.

The purported charge was that Moore and his publishers had composed, printed and published ‘a blasphemous libel of the Holy Scriptures and of the Christian religion in a book called The Brook Kerith’. Douglas’s solicitor referred to passages in the book which were ‘an affront and irreverence of the Christian religion’, and which perverted the Gospel narrative. The book, he said, was intended to hold up the Christian religion to ridicule and contempt by suggesting that ‘our Lord Jesus Christ was an ignorant, deceitful, violent-tempered person and a vainglorious impostor’.

Case dismissed

The case got short shrift; the magistrate said that the passages did not constitute blasphemy. The book was based on the assumption that Christ was merely a man and not a Divine person, an assumption that the author had a perfect right to make. He refused the application. The report was carried verbatim in the Irish Times, the Irish Independent, the Freeman’s Journal and also, later that week, in the Connaught Telegraph.

The Brook Kerith: a Syrian story was published in August 1916. With the boost given to sales by the blasphemy action, demand exceeded supply and within a month it had gone into its fourth printing and sold 5,000 copies. It was controversial from the start; the London monthly The Academy declared it ‘quite the most disgraceful and malicious thing that mortal man has hitherto had the impertinence to offer us’. The Daily Express called it ‘contradictory, stilted, peppered with anachronisms, irritatingly mannered and blatantly vulgar’.

But others loved it. The English Review called it ‘an astonishing tour de force, incontestably a great book, a modern classic … a gem of exquisite English, of a quite haunting charm, of an abiding beauty. It is Moore’s chef d’oeuvre, the effort of a true artist.’ Vanity Fair adjudged Moore ‘the best living English novelist’, Dial placed Moore ‘in the company of Rembrandt’ and The New Republic saw in it ‘George Moore at his best’. A later critic, Humbert Wolfe, hailed it as ‘the greatest single literary achievement of our time’ and as ‘possibly the greatest prose book in the English tongue, except the Bible’.

Ignored in Ireland

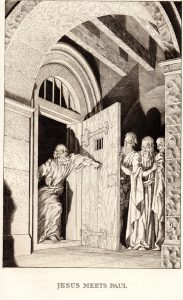

Above: ‘Jesus meets Paul’, one of twelve engravings by Stephen Gooden in a limited 1929 edition of The Brook Kerith. In the book Moore makes Paul the Apostle the real creator of organised Christianity.

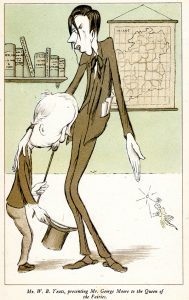

But the newspaper-reading public in Ireland could know little of these denunciations and eulogies. The book, apart from the court report, was almost totally ignored in Moore’s homeland. It was not that Moore was of no interest to Irish readers. He had lived in Dublin for the decade from 1901 to 1911, and had played a prominent role with Yeats in establishing the Irish Literary Theatre. During that period he had published half a dozen books, including Ave, the first volume of his autobiographical trilogy Hail and farewell. Volumes two and three, Salve and Vale, which came out in 1912 and 1914, after Moore had returned to London, had delighted and infuriated Dublin with their portrayal of the weaknesses, foibles and eccentricities of Dublin society—mainly Moore’s erstwhile friends.

The Irish Independent seems to have been the only Dublin newspaper to express an opinion on The Brook Kerith. In a short notice headed ‘George Moore’s Blasphemy’ carried before the London court case, it commented:

‘Mr Moore gives his version of the life of Our Divine Lord. Denying the Divinity of Christ, he makes his story run that Jesus was taken down from the Cross before he was dead and placed in the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea who then discovered that he was alive … That a mind like George Moore’s should dwell on the sacred theme of Our Lord’s life, death and Passion is marvellous. That such a mind should recast the Gospel narrative is an abomination.’

Above: W.B. Yeats presenting Mr George Moore to the Queen of the Fairies by Max Beerbohm, early twentieth century. Moore had played a prominent role with Yeats in establishing the Irish Literary Theatre, forerunner of the Abbey. (Dublin City Gallery: The Hugh Lane)

A week after the court case, the Irish Times carried a discreet single paragraph taken from the London Times Literary Supplement’s review of the work:

‘No one, however orthodox, could honestly be shocked by the book. It is a beautiful story … This book is a tribute—there never was a stranger one—to the charm of Jesus … He is once again a real living person to Mr Moore, and the most interesting person in the world. That, no doubt, is why he has written this book about Him, and not because he wishes to express his disbelief in orthodox Christianity. And that too is why the book is so good.’

But the Irish Times did not see fit to review the book. The volume that was generating columns of comment in newspapers and journals in London, New York, Paris and elsewhere was ignored in Ireland. Moore later wrote of ‘the fright’ the book caused among critics when it first came out, and how ‘again and again the book was returned (by critics) to the editors who had sent it out’. We know that the Irish Times got its copy, for it is listed on 16 September, among ‘Publications Received—The Brook Kerith: A Syrian Story, by George Moore. Werner and Laurie 7s/6d.’

Irish critics and editors may have taken fright. Some might argue that there were more important things to write about—the centre of Dublin was still in ruins following the Rising, some printing businesses had been damaged and some publications had been suspended. The Great War was at a critical stage. But the newspapers, dailies and weeklies still came out, as did journals such as Irish Homestead, Irish Monthly, Studies and Irish Booklover, all of which carried book reviews—but none of The Brook Kerith. This ignoring of Kerith seemed all the more pointed when Moore’s brother Maurice’s biography of their Home Rule MP father was widely reviewed, as was a short book on Moore himself by Susan Mitchell, both published barely a month after Kerith.

Above: The family seat, Moore Hall, Carra, Co. Mayo, today.

Cutting Moore down to size

Moore had been delighted when Miss Mitchell, a friend of long standing, was commissioned to write the volume on him in the series Irishmen of today, published by the Dublin firm Maunsell. But he was not delighted when he read it. As well as being editorial assistant to AE (George Russell) at Irish Homestead, Susan Mitchell was a poet and a prominent writer. Like others, she had been incensed at Moore’s demolition of some of the leading luminaries of the Dublin cultural scene in the Hail and farewell trilogy.

Her book was a repayment in kind. It is almost a parody of Hail and farewell, written in the same gossipy style and treating her subject in the same witty and merciless manner as he had treated Hyde, Yeats and others. But it is not entirely a demolition; she devotes two chapters to The Brook Kerith which amount to a serious and generally sympathetic analysis, praising it while, as a practising Christian, questioning the motivation for writing it. In dealing with Kerith she drops the teasing, facetious style employed in the rest of the book to suggest that George Moore is not an entirely serious person. She sees in Kerith some of ‘his best writing’. She quotes ‘beautiful passages’, which she says ‘give some idea of the musical undertone in which the book is written’.

Nevertheless, the real purpose was to cut George Moore down to size. She suggests that his abrupt departure from Dublin for London in 1911 when the Home Rule crisis was coming to the boil was an act of betrayal. In the heightening nationalist fever in the summer of 1916, recollection of Moore’s savage criticism of Ireland and things Irish in Parnell and his island (1888), A drama in muslin (1886) and The untilled field (1903), never mind Hail and farewell, would have left many in Dublin in no mood to accord Mr Moore a literary triumph.

AE’s reaction

The news that the book was a rewriting of the Gospel story in which Jesus did not die on the cross, written by a man born a Catholic who became a bitter critic of Catholicism and who had then publicly converted to Protestantism, made any literary triumph even less likely. Miss Mitchell’s account of his conversion is more pantomime than spiritual struggle, as, indeed, was Moore’s own retelling of the event. The dedication in Miss Mitchell’s book is to ‘AE’ and John Eglinton, ‘who alone were treated mercifully by the author of Ave, Salve and Vale and who are therefore not likely to be indignant at the association of their names with this study of George Moore’.

As a prominent theosophist, AE would have been less likely than most in Dublin to be offended by the theology of Kerith, and he had been spared the sharpest of Moore’s barbs. He had been amongst Moore’s closest companions in Dublin. Yet the Irish Homestead, of which AE was the long-standing editor, very pointedly did not review The Brook Kerith. AE had found something in Vale to be indignant about. Responding to a jibe from AE that his portrayal in the two earlier volumes of the trilogy had been unduly saintly, Moore had jokingly undertaken to find something sinful to remedy that in the third. What appeared was an off-hand reference to AE’s ‘neglect’ of his wife. As it was widely believed in Dublin that AE had been for some time in a relationship with his editorial assistant, the aforementioned Susan Mitchell, which was more amorous than administrative, this was read by many as a sly reference to the affair.

AE reviewed Mitchell’s book on Moore in the Irish Homestead of 14 October 1916. Referring to Moore as ‘this indefatigable gossip’, he wrote that ‘Miss Mitchell has wittily adopted his own method and has written about him in a frankness, half kindly, half malicious, which is the counterpart of his own frankness’. In giving her own pen portraits of many of those portrayed ‘more vividly than justly’ by Moore in his ‘notorious trilogy’, ‘she takes the opportunity of kindly redressing a balance in favour of those unjustly treated’.

King James Bible

AE manages an oblique dig at The Brook Kerith by reminding Moore of ‘the truth of the Scripture which says, “With what measure ye mete, it shall be measured unto you”’. This is not just from the Bible but from the 1611 Authorised (King James) English version (AV), which Moore tells us he had been reading, and greatly admiring, for many years. The Brook Kerith is Moore’s tribute to the AV, written almost entirely in its style. At almost 500 pages it is a formidable work. But it is also a wonderfully told story, particularly to any reader familiar with the King James Bible. It may deny the divinity of Christ, but it is not crudely anti-Christian; it reflects Moore’s own struggle with religion, from his own early refusal ‘to confess’ when a school boy with the Jesuits to his later adoption of his own form of Protestantism, which did not require a belief in the divinity of Jesus. That was not an entirely new idea when he wrote Kerith, but it has since become a commonplace of modern theology. In Kerith Moore makes Paul the Apostle the real creator of organised Christianity—something now generally accepted.

Though Moore himself at times declared The Brook Kerith his greatest work, it is probably, of his 60 or more books, among the least read today. At an academic level, Moore’s great significance in the history of both English literature in general and Irish writing in English as it evolved and flourished in the early twentieth century is still widely recognised. Scholars continue to analyse and debate his work, some of them in the Moore Institute for Research in the Humanities and Social Studies attached to NUI Galway. It was so renamed in 2006—not, sadly, after George Moore himself but after the Moore family, bracketing George with his father, the Home Rule MP, and his younger brother, the pious Maurice, with whom George agreed on almost nothing, and even possibly with George’s great-uncle John, briefly, in 1798, the first and only president of the Republic of Connacht.

The mummer’s wife and Esther Waters are acknowledged landmarks on the journey of English literature from the Victorian era to the brutal realism of modernity, as are, in Ireland, The untilled field, The lake and A drama in muslin. Many of his books have been issued in modern paperbacks—The Brook Kerith made it into Penguin in 1952. Almost all are easily and cheaply available today, but George Moore remains a shadowy figure to the wider reading public, not up there in the pantheon with Yeats and Synge, or Swift, O’Casey, Shaw and Wilde.

Above: A Penguin first edition, 1952.

When Moore died in 1933 the Irish Times carried a long obituary to ‘the well-known Irish man of letters’, discussing many of his books but giving The Brook Kerith no more than a passing nod, describing it as ‘a long book, published in 1916’, and adding that but for men’s preoccupation with the events of the Great War it would undoubtedly have caused a great stir. Some celebration of George Moore on the centenary of The Brook Kerith might leaven the unhealthy diet of guns, martyrs and narrow nationalism that has characterised 2016 so far. There must be in Ireland, somewhere, an appreciation today, warmer than in 1916, of a man who could ask in 1903, ‘When will my unfortunate country turn its eyes from Rome—cause of all her woe?’, of a man who could denounce racial hatred of England as the dominant strain in Irish nationalism, and who could insist that England and Ireland belonged together as part of a European, English-speaking culture.

Dennis Kennedy is a former Deputy Editor of the Irish Times.

FURTHER READING

A. Frazier, George Moore 1852–1993 (New Haven and London, 2000).

S.L. Mitchell, George Moore (Dublin, 1916).

C. Montague & A. Frazier (eds), George Moore, Dublin, Paris, Hollywood (Dublin, 2012).