Bringing it all back home: O’Connell, Douglass and Barack Obama

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 4 (July/August 2011), News, Volume 19

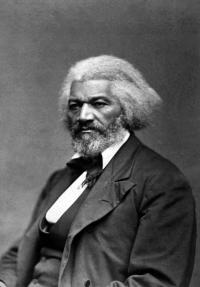

Frederick Douglass, the ‘Black O’Connell’

On 20 September 1845, The Nation advertised:

‘Frederick Douglas [sic], recently a slave in the United States, intends to deliver another lecture in the Music-Hall, Lower-Abbey street, on Tuesday evening next, 23rd instant, at eight o’clock. Doors to be open at half-past seven o’clock. Admission, by tickets, to be had at the door. Promenade—fourpence. Gallery—twopence.’

The 27-year-old Douglass, an escaped slave, had rendered himself famous with the publication of his bestselling Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. He arrived in Dublin in August 1845 and stayed in Ireland for four months. He delivered highly successful and well-received abolitionist speeches in Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Belfast. His flamboyant and hard-hitting oratory, combined with sensational props—whips, handcuffs and chains—made him a hit.

In September 1845 he met his hero, Daniel O’Connell, who introduced him to a Repeal meeting as ‘the Black O’Connell’. Douglass had long admired ‘the Liberator’ for his principled stand against the ‘foul stain’ of American slavery, and the leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had named his newspaper The Liberator in his honour. O’Connell had contemptuously dismissed Irish-American money from slave states: ‘I want no American aid, if it comes across the Atlantic stained in American blood’. O’Connell never wavered on slavery, and sought to link Irishness and opposition to oppression ‘wherever it rear[ed] its head’. He asserted that ‘Ireland and Irishmen should be foremost in seeking to effect the emancipation of mankind’, because the Irish ‘had themselves suffered centuries ofpersecution’. With Douglass in the audience he uttered the powerful words:

great-great-granddaughter Nettie Washington Douglass and her son Kenneth Morris being greeted by the director of the Keough Naughton Notre Dame Centre, Kevin Whelan, at the doorway of 58 Merrion Square, once the residence of Daniel O’Connell and now home of the Centre. (George K. Warren)

‘My sympathy with distress is not confined within the narrow bounds of my own green island. No—it extends itself to every corner of the earth. My heart walks abroad, and wherever the miserable are to be succoured, and the slave to be set free, there my spirit is at home, and I delight to dwell.’

O’Connell called for ‘speedy, immediate abolition’ in 1831 and attacked the white republic and American hypocrisy, remaining consistent and principled on this issue even when it hurt him with the Irish-American constituency. In his opinion, shared oppression should have nurtured a political affinity between Irish Catholics and African-Americans, and he was puzzled as to why the Irish embraced ‘cruelty’ in America by supporting the slavery cause. O’Connell personally declined to set foot in the USA while it remained a slave society. His efforts were recognised within America. In 1833 the African-American church in New York held a meeting honouring O’Connell, ‘the uncompromising advocate of universal emancipation, the friend of oppressed Africans and their descendants and the unadulterated rights of man’.

Douglass was enraptured by his Irish experience: ‘I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life.’ He was also heartened by the success of the edition of his narrative printed in Dublin by the veteran abolitionist Quaker R.D. Webb. Douglass had long wanted to visit Ireland. He credited his escape from Baltimore to the advice given him there by two Irish dockers, and he trained himself in oratory through studying the speeches in an American publication, The Columbian Orator of 1797 (‘Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book’), modelling his speaking style on that of Arthur O’Connor and Richard Brinsley Sheridan (‘I met there one of Sheridan’s mighty speeches, on the subject of Catholic Emancipation’). He was also inspired by O’Connell, and the style of African-American oratory was forged when this flamboyant Irish tradition fused with the call and response and testamentary preaching style of the African-American church. Douglass bequeathed that style to Martin Luther King, his great successor in the civil rights movement. In turn that style also informs the oratory of Barack Obama, who lists Frederick Douglass as his historical hero and role model. When the president spoke at College Green, he stood in front of a building, the Parliament House, which could be regarded as the birthplace of his speaking style, and he spoke warmly of the relationship between O’Connell and Douglass.

In the same week, the direct descendants of Frederick Douglass were for the first time visiting Ireland, at the invitation of Don Mullan. His great-great-granddaughter Nettie Washington Douglass and her son Kenneth Morris were warmly greeted by the president of Ireland, attended the launch of a new Dublin edition of the Narrative and visited Daniel O’Connell’s residence at 58 Merrion Square, now owned by the University of Notre Dame. It was a poignant moment. Like their ancestor, the Douglasses felt warmly treated in Ireland. On their taxi trip in from the airport, they were astonished when the driver refused to take a fare, saying that he regarded it as an honour to have them in his car. HI

Kevin Whelan is director of the Keough Naughton Notre Dame Centre in Dublin.