Breaking into Emergency Ireland

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2017), Volume 25The sharp debates currently surrounding the issue of immigration and the securing of borders call to mind a strange situation that the de Valera government faced as the Second World War came to an end.

By Bernard Kelly

In late 1944, Dublin and Belfast were both surprised to learn that London was about to transfer 10,000 German prisoners of war to Northern Ireland, in order to relieve the severe overcrowding in POW camps in mainland Britain. Any POWs who escaped and made it to neutral territory were, according to the 1907 Hague Convention Respecting the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Case of War on Land, immune from arrest and internment, as detaining them could be construed as continuing their original captivity. The Irish government was therefore presented with the potentially difficult situation of German POWs fleeing across the border and being at liberty in neutral Ireland, their immunity from arrest secured in international law. This could have been a diplomatic disaster for Dublin, at a time when Irish–Allied relations were already at a low ebb: in February 1944, the so-called ‘American Note’ demanded the expulsion of Axis representatives from Éire, and in September the Allies requested an assurance that Ireland would not grant asylum to any Axis war criminals, both of which de Valera refused. To avoid putting further pressure on an already strained relationship, the Dublin government decided to secretly jettison international law entirely and to rely on pre-war legislation, designed to restrict illegal immigration, to intercept and expel any German escapees found on the southern side of the border.

Stung by the lack of consultation on the transfer of the Germans, Stormont officials warned in December 1944 about the danger of ‘escapes to Éire and the likelihood of these men finding some sympathy with certain elements in our midst’. When informed of the situation, the secretary of the Department of External Affairs, Joseph Walshe, told Sir John Maffey, UK representative in Dublin, that the British ‘should take the greatest care to prevent them from escaping into our area’. The first prisoners arrived in January 1945. They were held in six wired camps that had previously housed American troops and also had a separate hospital at Orangefield, near Belfast, which was run by German staff but overseen by British officials. The RUC were authorised to use force to prevent escapes, but the Home Office strongly recommended that they exercise restraint. One German prisoner in Northern Ireland was killed during an escape attempt, shot by a sentry at Monrush camp in March 1945.

The legal adviser to the Department of External Affairs, Michael Rynne, was tasked by de Valera with looking into the legal aspects of the situation. The language of the 1907 Hague Convention did not provide much comfort:

‘A neutral Power which receives escaped prisoners of war shall leave them at liberty. If it allows them to remain in its territory it may assign them a place of residence.’

Other neutrals, such as Spain and Switzerland, arranged to hand over escaping Allied POWs to their home governments, while the Swedish regulations pointed out that escapees were not ‘internable’ and were to be turned over to the local authorities. The British and Irish manuals of military law offered Rynne some hope, however. Both stated that:

‘Prisoners of war who succeed in escaping into neutral territory regain their liberty, but they cannot claim to remain there. It rests with the neutral State whether it will grant or refuse them admission, and in the latter case whether or not it will allow them to remain on its territory.’

‘Zone of control’

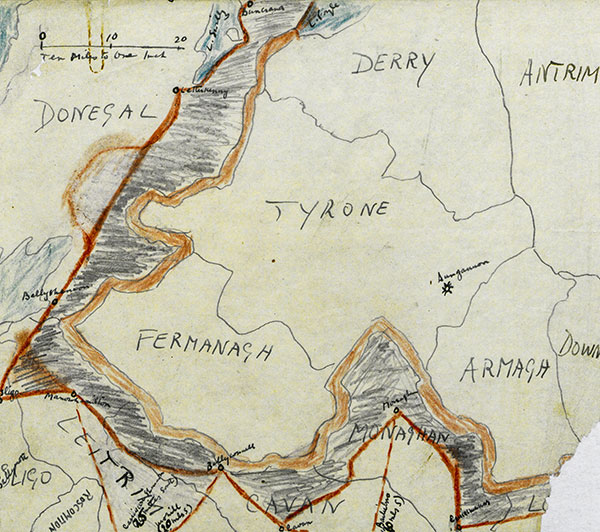

Rynne’s solution was to choose a middle way between the two extremes of interning escapees or leaving them at liberty. Noting that a neutral country could deny escaping POWs entry if it wished, Rynne suggested the creation of a special ‘zone of control’ along the border with Northern Ireland, extending approximately 35 miles into Éire territory. German prisoners who were caught within this zone were considered to be still in the act of escaping and could therefore be turned back. De Valera himself approved this idea on 13 January 1945. The key to the Irish strategy was to prevent escapees from getting into the interior of Éire but, as Rynne noted, the Gardaí would not be able to contain a mass break-out from Northern Ireland and the fate of those who managed to slip past the ‘zone of control’ was not discussed.

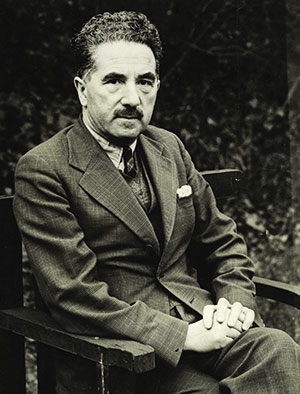

Above: Michael Rynne, legal adviser to the Department of External Affairs, suggested this ‘zone of control’ within which German POWs were intercepted and returned to Northern Ireland. (NAI)

To enforce the policy, the government relied on the pre-war Aliens Act of 1935. This gave the minister for justice the power to prevent aliens from entering the country, and Gardaí were to ascertain whether any Germans caught within the 35-mile corridor had the correct documentation allowing them to cross the border. If they did not, they were to be ‘escorted without delay to the Border and put across into Northern Ireland’. Escaping POWs would not, of course, have the correct permits or a passport, meaning that they could all be expelled without recourse to international law. The manner in which POWs were returned to Northern Ireland also had to be handled very carefully. The Gardaí were specially instructed that they ‘will not be formally handed over to the RUC’, and Walshe informed Maffey that they could not be directly handed back because of the implications for Irish neutrality. In the end, Gardaí were told simply to drive escapees to the border and release them across it: as Col. Dan Bryan of G2 (military intelligence) said, POWs were to be ‘pushed back’. Within 48 hours of the decision being made, two German POWs appeared in Dundalk and handed themselves in to the local Garda station. They were part of a group of four who had escaped from a camp in Gilford, Co. Down, two of whom had been intercepted by the British. As they had been found within the ‘zone of control’, the two men were given a cup of tea, then driven to the border and went ‘quite cheerfully’ when they were sent back into Northern Ireland. In July 1945 a further two Germans were discovered in Louth; documents show that de Valera himself ordered that they be ‘sent across the border’. In total, only twenty Germans escaped from camps in Northern Ireland, and very few of these made it across the border. Of those who arrived during the conflict, all were detained by the Gardaí for a short period and then ferried back to Northern Ireland. Escape was extremely difficult, as the POW camps in Northern Ireland were guarded very tightly, and POWs did not stay long in Northern Ireland: 8,000 returned to Britain in August 1945, and by December there were only 997 left in Northern Ireland.

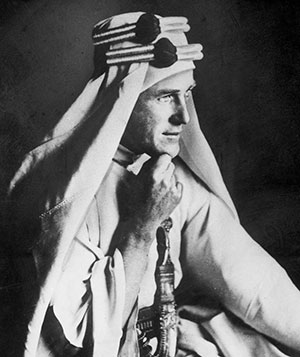

Above: Joseph Walshe, secretary of the Department of External Affairs—when informed of British plans to transfer 10,000 German prisoners of war to Northern Ireland, he told Sir John Maffey, UK representative in Dublin, that the British ‘should take the greatest care to prevent them from escaping into our area’.

In early 1946, however, more German POWs arrived from an unexpected direction. On 19 January, a small coastal patrol boat containing fifteen German sailors arrived in Kinsale harbour, having escaped from the French naval base at St Nazaire. They requested that they be repatriated to their homes in the British and American occupation zones of Germany; failing that, they wished to be given asylum in Ireland or to travel onwards to Britain. As the war was over, the government decided to expel them, again using the 1935 Aliens Act, and a French corvette arrived at Cobh on 7 February 1946 to bring them back. Michael Rynne justified this by noting that the conclusion of the war meant that the sailors were no longer escaping POWs but instead could be considered ‘ordinary aliens’ who had landed without a permit and were therefore liable to expulsion. A more important reason for handing them back was, in Rynne’s words, to avoid Ireland’s becoming ‘a refuge for all the displaced persons of Europe with the means of landing unexpectedly here’. Likewise, Joseph Walshe said that the sailors had been expelled purely because they were illegal immigrants and that, if they had been allowed to remain, Ireland would become ‘a happy hunting-ground for every kind of “displaced person” who manages to get here from Europe’. This directly echoed British actions in deporting Poles who arrived in the UK illegally after the war; the Home Secretary James Chuter Ede said that ‘it is essential that no encouragement should be given to the idea that persons who come to this country illegally will receive preferential treatment’. An External Affairs note for de Valera pointed out that Ede’s ‘statement covers our position as regards the fifteen Germans at Kinsale very accurately’.

Government decisions around German escapees from Northern Ireland and the Kinsale sailors were shrouded in heavy secrecy. In a meeting with Norman Archer of the British legation, Joseph Walshe stressed the need to stop the press publishing the news of escapes, and the official instructions issued to the Gardaí emphasised that the order to expel POWs was ‘strictly confidential’. The Irish censor removed an article in the Irish Independent that stated that two men had made it over the border; the articles that were allowed to be published were very light on details. The same concealment applied to the Kinsale sailors and the decision to hand them over to the French. ‘If it were possible to avoid disclosing the details of this situation to the Dáil, so much the better,’ wrote Rynne. ‘Such a disclosure might have a bad effect abroad, as well as on the deputies.’ In addition, once the arrangements with the French government had been concluded, Frederick Boland, assistant secretary at External Affairs, telephoned the Department of Justice and warned them against arresting the sailors too early in advance of the French arrival, as that would give their lawyers time to file habeas corpus applications. He was told that the Gardaí had decided to ‘postpone the arrest until the last moment’.

Avoiding habeas corpus cases was essential because Dublin recognised that its actions were legally very dubious. Michael Rynne acknowledged in 1948 that any legal action taken by escaped POWs against their expulsion by Dublin would be difficult to defend. Putting together a hypothetical court case brought by an escaped POW against the Irish state, he argued that, even if the court found against the applicant,

‘… despite this Department’s assurances that Ireland has overtly assumed all the obligations of the Hague Conventions, and, in particular, those deriving from Convention No. V of 1907 concerning the rights and duties of neutral powers in case of war on land, it is scarcely conceivable that it could, on the basis of this Department’s replies, permit deportation to any place at which the alien might again be taken into British custody.’

In other words, even if the court turned down the prisoner’s plea against his expulsion, the escapee could not be sent back to his original captor. This, however, is precisely what happened when de Valera ordered that German POWs be transported back over the border into Northern Ireland.

Above: Sir John Maffey (in bowler hat, bottom left-hand corner) with de Valera at the handing over of Spike Island in 1938. Also in the picture are Major Vivion de Valera, Frank Aikan, Senator Eoin Ryan, Oscar Traynor and Kevin Boland. De Valera and Sir John Maffey had a good working relationship throughout the war, and in many cases, such as that of the German POWs, de Valera was willing to accede to British requests, even if they contradicted Ireland’s neutrality.

Evaded its responsibilities as a neutral

In dealing with both POWs escaping from Northern Ireland and the Kinsale sailors the Irish government evaded its responsibilities as a neutral, which were specified under international law in the 1907 Hague Convention. As Michael Rynne admitted in January 1946, Dublin was technically supposed to allow escaping prisoners of war to attempt to rejoin their own forces, as Switzerland did. The government’s priority, however, was to maintain relations with the Allies, which had been heavily damaged during the war. Allowing escaping German POWs to remain free in neutral Ireland would not only cause another diplomatic incident but could also be used by those who wished to depict the de Valera government as pro-Axis. Using the 1935 Aliens Act allowed Dublin to neatly sidestep its obligations, and in the process categorised escaping POWs as foreign nationals attempting to make an illegal entry into Éire, almost as if the war was not happening. The orders issued to the Gardaí make no mention of prisoners at all and instead consistently refer to them as ‘aliens’. The use of existing legislation, the convenient classification as aliens and the use of censorship to remove all mention of the escapees in the Irish media, at least during the war, meant that the government could quickly and quietly deal with any escaped POWs and avoid any unpleasant explanations either to the Dáil or to the Allies. As in most cases during the Second World War, when faced with either a breach with the Allies or compromising Irish neutrality, the de Valera government chose the latter.

Bernard Kelly is an Honorary Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

FURTHER READING

B. Kelly, Military internees: prisoners of war and the Irish state during the Second World War (London, 2015).

D. Leach, Fugitive Ireland: European minority nationalists and Irish political asylum, 1937–2000 (Dublin, 2009).