BRAM STOKER’S ‘GREAT GAME’?

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2022), Volume 30By Martin Greene

Above: Bram Stoker in 1884. He first met Arminius Vambéry five years later in the Lyceum Theatre in London, where he had been the general manager since 1878. (Stoker–Dracula Organisation)

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the leader of the group of vampire-hunters, Van Helsing, is qualified to play this role because he can call on the expertise of his ‘friend Arminius of Buda-Pesth’. The real-life Arminius Vambéry was a professor of oriental languages at the University of Pest and a celebrated explorer of Central Asia. He was a frequent visitor to England, where his books were published and he had influential connections. What was not generally known at the time was that he was also a paid agent of the British intelligence services. This means that he was a player in the so-called ‘Great Game’—the nineteenth-century competition between Russia and Britain for dominance in Central Asia. His connections with the intelligence services may also explain why he wrote to the London Times in 1887 opposing Home Rule for Ireland.

A GREAT GAME?

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, Britain was the leading world power and Russia was its closest rival. The competition between them was focused mainly on the Black Sea/eastern Mediterranean area, and specifically on the struggle for control of the Strait of Bosporus as the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire declined. Other regions in which there was significant Anglo-Russian competition included Persia/the Persian Gulf, the Far East and Central Asia. In Central Asia, the competition was concerned with the area between the Russian Empire and British India. This was a vast expanse of territory corresponding to today’s post-Soviet republics in Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan), Pakistan and large parts of northern India and western China. Central Asian cities—Samarkand, Tashkent, Bokhara, Khiva—played a vital part in the fabled ‘Silk Road’ trade networks, which connected Europe with Asia in classical times, and in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Samarkand was the centre of Tamerlane’s extensive empire, which spanned Persia, Central Asia and northern India. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, the area was effectively isolated from the outside world.

At the outset of the struggle for dominance in this area, the distance between Russia and British India was over 2,000 miles. The intervening territory was a land of deserts, steppes and near-impenetrable mountains. The population was sparse, mostly Muslim and partly nomadic. It included established states but also extensive areas with no settled political structures. There were substantial physical barriers separating Russia and British India from Central Asia—a vast area of nomad-inhabited steppes on one side and the great mountain ranges to the north of British India on the other. And the imperial powers’ knowledge of the territories and societies in which they were about to intervene was astonishingly limited.

Yet neither side was willing to concede a dominant position in the area to the other. The underlying assumption was that the dominant side would use the area as a base from which to attack the other’s adjacent territory or (more realistically) that it would use the threat of doing so as a means of gaining leverage elsewhere.

The power play never escalated to the point of direct conflict between them. Instead, they strengthened their positions in the area by annexing some territories and forcibly absorbing others into their respective spheres of influence. They engaged militarily with regional and Central Asian states but never directly with each other. Among the regional states, Persia and Afghanistan were usually more or less within the spheres of influence of Russia and Britain respectively; China, though weak, was too big for sphere-of-influence treatment. The imperial powers ran into serious trouble in some of their campaigns against regional and Central Asian states (Britain/Afghanistan, 1838–42 and 1878–81; Russia/Khiva, 1839–40). In the end, however, their modern armies prevailed over poorly equipped local forces, sometimes with catastrophic losses for the defeated armies and their camp-followers.

By the 1890s, most of the territories in contention had been annexed by either Russia or British India, thereby reducing the distance between them to a few hundred miles, and at one point to less than twenty miles. Russia had annexed Western Turkestan, the Muslim, mainly Turkic-speaking territories of Central Asia, including Samarkand, the Khanates of Khiva and Khokand, the Emirate of Bokhara and extensive nomad-inhabited areas. British gains included substantial territories to the north of British India, including Sind, the Punjab, Kashmir and Baluchistan. Persia and Afghanistan remained nominally independent. Eastern Turkestan (the part of western China inhabited by Muslim, Turkic-speaking peoples) remained within the Chinese Empire, thereby storing up problems for the future in the form of a Uyghur minority in the Chinese state.

The potential for imperial expansion in the area had now reached its limits and the growth of German power and assertiveness had given the other powers a reason to avoid conflicts with each other. In 1907 the Anglo-Russian Convention (negotiated by Russia and Britain above the heads of all other interested parties) confirmed the borders as they stood at that point.

The term ‘the Great Game’ was in use among British military officials in India throughout this period—evidently a show of bravado on their part. In 1901 Rudyard Kipling used it in Kim, thereby fixing it in the popular imagination as the default term for referring to this exercise in competitive imperial expansion.

Above: Arminius Vambéry—professor of oriental languages at the University of Pest and a celebrated explorer of Central Asia. (Alamy).

ARMINIUS VAMBÉRY

Arminius Vambéry was born in the early 1830s to a poor Jewish family in an area of western Hungary that is now part of Slovakia. His full-time education ended when he was eleven years of age, but he nevertheless mastered the principal languages of his home area (Hungarian, German, Slovak) while still a teenager. This enabled him to earn his living as a private tutor while continuing his personal studies, which now included additional languages (Russian, Turkish, French) and philology.

In 1857 he moved to Turkey to pursue his philological studies. Spending six years in Constantinople, he immersed himself in Turkish culture and widened the focus of his studies to include Islamic doctrine and practice. His next move was to Persia in 1863. After spending just under a year in Teheran, he took a place in a caravan bound for Central Asia, travelling as Reshid Effendi, a Baghdadi dervish (holy man) who was making a pilgrimage to the Muslim holy places along the route.

He spent six months on what was both an arduous and a perilous expedition, visiting Bokhara, Khiva and Samarkand, acquainting himself with the Turkic dialects of Central Asia and studying antiquities and manuscripts that had been seen by few other European explorers. At each location he was questioned by the authorities about his identity and the purpose of his travel—failure to pass muster on these occasions would have had the most serious consequences. In the event, he completed the expedition unharmed and with his disguise intact—a remarkable achievement. Promptly on completion of what would be his only expedition of this kind, he returned to Europe and embarked on several interlocking careers. In Hungary he was appointed professor of oriental languages at the University of Pest. He was also able to pursue his career as a philologist from his base in Pest, drawing on his research in Turkey, Persia and Central Asia to publish well-regarded scholarly works.

Visiting England soon after his return to Europe, he found that a career as a celebrity explorer was there for the asking. He was inundated with offers of publishing contracts and speaking engagements, and the doors of influential institutions and individuals were open to him. For the best part of the next 40 years, he managed his career as a celebrity explorer on the basis of regular visits to England from his base in Pest.

State papers released only in 2005 show that from the early 1870s he had yet another career as a paid agent of the British intelligence services. His role was advisory rather than operational except that he acted for a time as an intermediary between London and Constantinople—leading to suggestions that he was a double agent. He was also actively involved in the lively public debates in England relating to Central Asia—the State papers show that the intelligence services valued him as much for his contribution to these debates as for his advice on policy issues.

In his interventions in public debate, he always took a strenuously anti-Russian line, advocating a vigorous British response to Russian advances in Central Asia. He was also strongly supportive of Empire, reasoning that the peoples of Central Asia and similar regions were not ready for self-rule. His arguments were specifically supportive of the British Empire—suggesting that Britain’s liberal traditions, institutions and practices meant that colonised peoples were best served by inclusion in the British rather than any other empire. As David Mandler has noted, however, he reflected ruefully in a memoir published when he was in his 70s that ‘our high-sounding efforts at civilisation in the East were but a cloak for material aggression and a pretext for conquest and gain’.

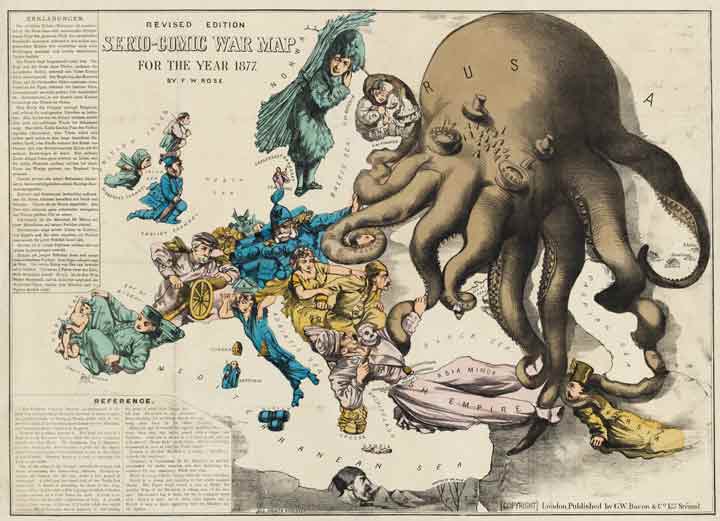

Above: Fred W. Rose’s ‘SERIO-COMIC WAR MAP FOR THE YEAR 1877’, presenting Russia as a giant octopus with tentacles reaching to areas of great power competition. Different countries are reacting in different ways to Russian expansionism (England looking calculatingly at Russia and thinking ‘Suez, India, £.s.d.’; Ireland looking thoughtfully at England’s back and thinking ‘Home Rule’). The easternmost tentacle ensnares four of the Central Asian territories annexed by Russia—Samarkand, Khiva, Bokhara and Khokand, all but the last-mentioned visited by Arminius Vambéry. (Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center, Boston Public Library)

STOKER AND VAMBÉRY

Bram Stoker first met Vambéry in 1889 through the Lyceum Theatre in London, where since 1878 he had been the general manager and where Vambéry was an occasional guest at events hosted by the theatre proprietor, Henry Irving. They met again later that year at an event at the royal residence at Sandringham at which Vambéry was a guest and the Lyceum provided a theatrical performance. The guests were mainly family and notables from the locality, but Vambéry was included because Edward Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) considered him to be a personal friend. There was a further meeting in 1892 at a ceremony in Trinity College Dublin at which both Vambéry and Irving received honorary degrees. Stoker (present as Irving’s guest) mentions this event in his Irving memoir published in 1906, commenting that Vambéry made an excellent speech in which he ‘spoke loudly against Russian aggression’. The Vambéry biographers, Lory Alder and Richard Dalby, add that the speech was ‘glowing with generous admiration of the British people and their empire’.

The early readers of Dracula (1897) would have been familiar with Vambéry’s reputation as an explorer of remote areas and an authority on the arcane forms of knowledge that were supposed to exist in such areas. They were probably therefore predisposed to accept him in his role as Van Helsing’s adviser. His links to the intelligence services—if they had somehow come to public notice—would have undermined his claim to be a disinterested participant in public debate. Even in that case, however, readers might have seen his involvement in deceits and intrigues—in the context of a deadly struggle against vampirism—as an additional qualification for the role.

For Stoker, the assignment of ‘Arminius of Buda-Pesth’ to the role solved a compositional problem—how to buttress Van Helsing’s credibility as the chief vampire-hunter. And yet reasonably well-informed readers might have wondered whether he was also playing a game of his own at the imperialists’ expense by simultaneously solving a compositional problem and inviting attention to the reputation of a leading ‘Great Game’ propagandist—a reputation that might not stand up to scrutiny.

OUTCOMES

On publication, Dracula initially met with a muted reception, but it would later—though only after Stoker’s death—win critical and popular acclaim as an outstanding work of fiction. It would also have an extraordinary impact on popular culture over the next century and beyond. Vambéry’s secret remained safely under wraps for another century. Stoker’s game—if there was one—didn’t result in his unmasking.

In Central Asia, local populations suffered most from the turmoil unleashed by a century of competitive imperial expansion, and in the end Russia and Britain negotiated a carve-up of the territory regardless of the wishes of its inhabitants. For the peoples at the sharp end of imperial expansion, the ‘Great Game’ was neither ‘great’ nor a ‘game’.

Martin Greene is an independent researcher.

Further reading

L. Alder & R. Dalby, The dervish of Windsor Castle: the life of Arminius Vambéry (London, 1979).

M. Ewans, Securing the frontier in Central Asia (London, 2010).

D. Mandler, Arminius Vambéry and the British Empire: between East and West (Lanham, Maryland, 2016).

A. Morrison, The Russian conquest of Central Asia: a study in imperial expansion, 1814–1914 (Cambridge, 2021).