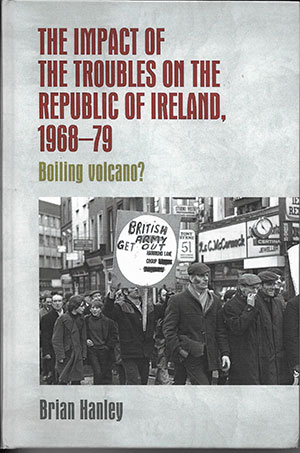

The impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968–79: boiling volcano?

Published in Book Reviews, Issue 1 (January/February 2019), Reviews, Volume 27BRIAN HANLEY

Manchester University Press

£80/€93.75

ISBN 9780719091131

Reviewed by: Martin Mansergh

Martin Mansergh is a former government adviser and politician.

Martin Mansergh is a former government adviser and politician.

One of the most natural human tendencies is to try and sanitise narratives of the past, to smooth over the jagged edges, the mistaken actions and judgements, and, if possible, to cover them with a principled consistency of purpose. An indispensable role of the historian is to recreate the complex and often confused reality, often full of contradictions, and to remind people of inconvenient truths.

Despite a vast literature on the Northern conflict, the impact of the Troubles on the Republic during the 1970s in terms of public reaction, outside of high politics, has been infrequently studied. Brian Hanley, while acknowledging the difficulty of the task, has done an exceptional job in trying to fill the gap. For nearly the first half-century of independence and partition, Northern Ireland was for most people in the Republic out of sight and out of mind, notwithstanding occasional bursts of political or armed militancy. The long, slow process of improving North–South relations after the Lemass–O’Neill meetings in the 1960s was overtaken by events, as northern nationalists found in civil rights, following high-profile examples abroad, the means of at last prising open fundamental change. Growing confrontation on the streets, reaching a climax in Derry in August 1969 that forced British army intervention, given the incapacity of the Stormont government and its local forces, also put the Republic under the spotlight. It highlighted the gap between ‘united Ireland’ rhetoric as the answer to everything and the need for practical responses to a crisis situation. Thanks as much to television as geography, the problem that had been festering away barely noticed had suddenly erupted.

With the Unionist government in deep trouble, unable because of internal divisions to spearhead the reforms the British government required in the face of international opinion, it was easy but fatally wrong to conclude that with one more push partition would be gone, or to assume that the struggle for independence could be completed by the same methods used in 1919–21. Curiously, the first assumption was shared by Lynch’s young and forceful justice minister, Desmond O’Malley, when in 1972 he denounced illegal subversive organisations for potentially thwarting the end of partition ‘now within our grasp’, potentially ‘in the lifetime of our great founder’ (President de Valera was 89).

There was an old Soviet joke that ‘while the future is certain, the past may be unpredictable’. Brian Hanley includes many startling reminders. Fianna Fáil actually announced in December 1970 that it was going to reintroduce internment. Kevin Boland, founder of Aontacht Éireann, claimed that the IRA was fighting the same war as at Crossbarry and Kilmichael during a mid-Cork by-election, where his candidate ‘bombed’. Desmond Fennell wanted an end to the cult of Wolfe Tone, because of his anti-Catholicism (even though he was a champion of Catholic rights). Michael Farrell of People’s Democracy regretted that Leinster House had not been burnt down along with the British Embassy in 1972. Kevin Myers resigned in protest from RTÉ when RTÉ’s Kevin O’Kelly was jailed for reporting an interview he conducted with IRA leader Seán Mac Stiofáin, who was solicitously visited by Archbishops McQuaid and Ryan after giving up his fast to the death. A future editor of the Sunday Independent condemned the public outrage caused by the bomb that killed five cleaning women at Aldershot as a nauseating show of middle-class hypocrisy. For most of the period covered in this book, Eoghan Harris was a leading critic within RTÉ of Section 31, and was transferred from the 7 Days production team following a complaint that a programme breached it from Minister Conor Cruise O’Brien. The Stalinist B & ICO recognised ‘the democratic validity of the present Northern Ireland State’.

People laudably change their minds over time, but few imitate St Paul, who, after his conversion on the road to Damascus, regularly reminded audiences that he had once persecuted Christians.

Two especially offensive and regrettable comments are mentioned. John Laird, hardline unionist, later free-spending chairman of a North–South Ulster Scots language sub-body under the Good Friday Agreement, viciously claimed that the Dublin and Monaghan bomb victims quietly condoned the IRA. Brian Lenihan in the heat of parliamentary debate described Protestant Fine Gael Senator Billy Fox as ‘a B-Special Republican’, echoing unsubstantiated rumours that may have led to his death at the hands of the IRA in 1974.

There were many small-scale loyalist bomb attacks in the Republic in the 1970s, not just the well-known ones. The IRA sometimes moved to discourage attacks on Protestants in the Republic, who, particularly away from the border, were no longer liable for the actions of their Northern co-religionists. What comes across most strongly from Hanley’s survey is the lack of understanding in the Republic of unionist determination to resist incorporation into a united Ireland and of the likelihood that any Irish Army incursion would be repelled by the British as forcibly as the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands, leaving Ireland far further back than we are today. Fortunately, there were enough level heads in government and civil service and amongst the shapers of opinion to underpin the stability of the state and the island against spasmodic but dangerous waves of emotion.