Bishop Robert Daly: Ireland’s “Protestant pope”

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2006), Volume 14

Late nineteenth-century evangelical preacher addressing a crowd under police protection. Daly’s evangelical Protestantism inspired his religion and his responses to the various issues he encountered during a long life. (Michael Tutty)

Robert Daly, Church of Ireland bishop of Cashel, Waterford and Lismore (1843–72), is now a largely forgotten figure. Yet for many years in the nineteenth century his was a household name among Protestants and many Catholics. Daly was a person who engendered controversy. To some he was a narrow-minded, bigoted and intolerant man, while to others he was a champion of Protestantism. What is not in doubt is that he was an important and significant member of the Anglican Church, of whom the religious historian James Godkin wrote in the 1860s: ‘He became not only primus inter pares among the evangelical clergy, but ultimately assumed the position and bearing of a Protestant pope’.

Early career

Robert Daly was born on 10 June 1783 at Dunsandle, Co. Galway. His father was the Rt Hon. Denis Daly, a well-known political figure and supporter of Grattan, Flood and Curran, who married Lady Harriet Maxwell, the only child and heiress of the first earl of Farnham. Much of this wealth was inherited by Robert Daly, who graduated from Trinity College in 1803 and was ordained the same year. He became an ardent evangelical as a result of Bible-reading and meetings with such luminaries of evangelicalism as W. B. Mathias, minister of the Bethesda Chapel, Dublin, and Peter Roe, rector of St Mary’s, Kilkenny. Daly’s influence in the evangelical world was felt from the time he became rector of Powerscourt in County Wicklow in 1814. His aristocratic connections and the patronage of Lady Powerscourt, who regarded him as her spiritual director, helped him to advance in evangelical circles. Glendalough was turned into a stronghold of evangelicalism, with Daly influencing many of the landowning families of Wicklow.

Powerscourt Estate, Co. Wicklow-Daly became rector of the parish in 1814. (National Library of Ireland)

The event that established Daly’s prominence among evangelicals was his participation in a debate at Carlow in November 1824 with four Catholic priests. This encounter took place at the height of the considerable excitement generated by the so-called ‘controversial meetings’. These were an important aspect of the religious tensions that characterised relations between Catholics and Protestants in the 1820s and were occasions where representatives of the two faiths engaged in public disputations about their creeds. Robert Daly was a trenchant opponent of the Roman Catholic Church. Like most ardent evangelicals, he regarded Catholicism as a pernicious faith, founded on superstitions and heresies that were perpetuated by a priesthood steeped in ignorance and obscurantism. The priests held a tyrannical sway over their flocks, reducing them to a state of servile spiritual thralldom. Daly believed that it was a religious imperative for convinced Protestants to counter the teachings of the Catholic Church. In the view of most Protestants, Daly and his fellow clergymen were the victors at Carlow. His appetite for controversy was whetted and he was to gain a reputation as an able defender of Protestantism. This reputation, together with his energy, wealth and connections, made Daly one of the country’s foremost evangelicals.

Appointment as bishop

On 13 December 1842 Robert Daly was instituted to the deanery of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. On the same day he was offered appointment to the vacant see of Cashel, Emly, Waterford and Lismore, which he accepted. At his consecration on 29 January 1843 the tone of his episcopate was heralded by the presence of a large assembly of evangelical laity and clergy. Daly began turning his new diocese into a bastion of evangelicalism. A cadre of committed clergymen being essential to achieve his objectives, he began encouraging, attracting and promoting clerics who shared his religious vision. He put much effort into instilling in them a sense of zeal and purpose. At his first annual visitation of the diocese of Waterford he enjoined on them the importance of residence in their livings and stated that he trusted that he would not be put to the pain of enforcing this requirement. This was a theme he repeated at intervals. He also emphasised the importance of pastoral care of parishioners by clergymen, this requiring a personal acquaintance with members of their flocks. In order to be able to impress on people the demands of true religion, Daly exhorted his clergy to display personal commitment to their religious calling in their own lives.

Famine and ‘souperism’

Daly was bishop during the calamity that was the Great Famine. He was an active participant in efforts to relieve sufferings in Waterford city. Two food shipments, sent by American Quakers, arrived in Waterford in June 1847. The distribution of this aid was entrusted to responsible local personages, among whom was Bishop Daly. The city was divided into districts, the bishop taking one, and he went around from house to house with tickets for coal, soup and clothing. He made contact with many influential people in England, allocating to each of them a particular parish or town in his diocese that they might ‘adopt’ as a special care.

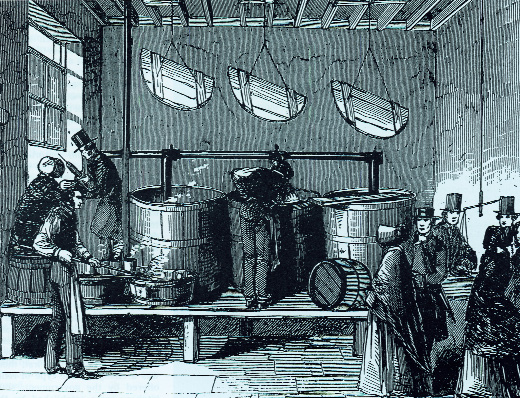

While Quaker kitchens such as this one in Cork distributed soup ‘with no strings attached’, Daly’s operation in Waterford was accused of ‘souperism’, the securing of conversions in return for soup. (Illustrated London News, 16 January 1847)

Carrick-on-Suir, for example, became the special concern of Blackheath, near London. Large collections were made in the English church every Sunday, averaging from £30 to £40, and sent the following day to the vicar of Carrick. Daly himself received large sums of money from England and he proved himself a judicious almoner. Bishop Daly’s efforts were praised by a Catholic priest, Revd John Sheehan, when proposing him for the chair of a new relief committee formed in the city in March 1847. Sheehan referred to the ‘great zeal and attention’ displayed by Daly for the interests of the poor.

The famine, however, caused religious divisions throughout Ireland, with some Protestant clergy and laity being accused of ‘souperism’, the securing of conversions through material blandishments, especially food, most commonly in the form of soup. Waterford was not immune to the poison of religious divisions. Allegations were soon being made in the local nationalist organ, the Chronicle, that Anglican clergymen were engaging in this practice in parts of the county. Daly was accused of inciting such activities. In the light of what was regarded as his unrelenting anti-Catholicism, the Chronicle declared its intention to ‘keep a lookout after the doings of the Rt. Revd. Perverter’. A Revd Fry was accused of souperism and was believed to be acting under the guidance of Daly.

While souperism was practised in Waterford, it was not widespread. The strongest indicator is the absence of substantial reportage in the Chronicle, an avowed enemy of the established church. What of the allegations directed at Daly personally? He certainly came to Waterford with a reputation for hostility towards their church in the eyes of many Catholics. At a time of religious tensions he was viewed with suspicion. His attitude to Catholicism may have encouraged some evangelicals to engage in souperism. There is no evidence, however, that Daly personally engaged in this practice. The many accusations made against him reflected a deteriorating religious climate, not actual deeds carried out by him. On the contrary, contemporaries praised Daly’s efforts at famine relief, as noted in the comments of Fr Sheehan.

Daly and proselytism

Whatever about souperism, Daly was passionate in his support of anti-Catholic missions, especially those engaged in proselytism. He proclaimed to his clergy in 1844 that ‘as long as we are in the land, it is our duty to protect her against error and preach the word of God to the people’. Daly was one of the founders in 1818 of the Irish Society or, to give it its full title, the Irish Society for Promoting the Education of the Native Irish through the Medium of their Own Language. As its name suggests, its activities were directed towards Irish-speakers. It aimed to promote the reading of scriptures in the native language, reflecting a fundamental evangelical belief that if Roman Catholics were exposed to the Bible they would realise the errors and heresies of the Roman Church. Daly played an important role in the society’s early successes, and during his time in Powerscourt he visited England every spring for three months to advocate its cause and raise financial support. When he became a bishop he continued this promotion, though for shorter periods of time.

Over a decade of religious strife in Ireland was heralded by the foundation of the Society for Irish Church Missions to the Roman Catholics in March 1849 by Alexander Dallas. With its headquarters in London, its English evangelical leaders, in cooperation with Irish sympathisers, attempted to effect the religious transformation of Ireland. The period 1849–54 was a heady time of Protestant religious crusading, but by 1860 this evangelical crusade was in decline. The Society for Irish Church Missions put great pressure on the Irish Society to join it in its efforts to convert Catholics. In 1853 an agreement was entered into by both societies ‘in order the better to extend the knowledge of the Gospel, and to avoid confusion and difficulties’. Under its terms there was a division of territory. Munster was to be the field of labour of the Irish Society; the Society for Irish Church Missions was to serve the rest of the country and it alone was to solicit funds in England.

Christ Church Cathedral, Waterford. (National Library of Ireland)

This alliance, which lasted three years, had the effect of making the Irish Society more aggressive in relation to the whole issue of proselytism. Daly was an enthusiastic supporter of Dallas’s campaign. At an Irish Society meeting in Waterford city in 1852 he spoke of what he described as ‘the wonderful reformation’ in the west of the country and how God was ‘wonderfully blessing’ the activities of the Irish Church Missions. He also enthused about the agreement between the Irish Society and the Society for Irish Church Missions, lauding it at the Irish Society’s annual meeting in 1854.

The mission at Doon

Daly’s militant evangelicalism was given practical expression in his hopes for a major proselytising success in his own diocese at Doon, and the adjoining parishes of Cappamore and Pallasgreen, all in County Limerick. In 1845 the rector of Doon, Thomas Atkinson, introduced the Irish Society into his parish. Initially it worked away unobtrusively, but the conversion of four Catholics in 1848 heralded a more aggressive and public phase of missionary activity by Atkinson and the Irish Society. More Catholics converted. Two scripture readers were appointed to give converts instruction in the reformed faith and they began their work in 1850. Before the end of the year six additional readers were employed. The rector built three schools, and in 1856 Daly consecrated a new church to accommodate the growing Anglican congregation.

In his work at Doon the rector had Daly’s full support. In fact, a Catholic priest at Cappamore was very definite in laying the blame for proselytism on Daly, whom he condemned as ‘a liberal contributor to the spread and support of apostasy here and elsewhere’. Daly and a Col. Lewis undertook to pay the salaries of the first two scripture readers. In 1851 the bishop sanctioned a fund-raising visit to England by Atkinson. When, at the instigation of Catholic clergy, shopkeepers at Cappamore refused to serve converts, Daly advised the establishment of a Protestant shop and advanced a loan towards the project. He enthused publicly about events at Doon and the other parishes. At the Irish Society’s annual meeting in Dublin in 1852 he spoke of ‘a great work going on’ and of ‘a great movement among the people’.

It is difficult to ascertain the exact number of converts, as this was a matter of controversy between Protestants and Catholics. Speaking in February 1852, Daly claimed that he had confirmed ‘many hundreds’ of converts the previous September. When the new church was consecrated at Doon in 1856 the congregation, according to the Irish Society, contained 400 converts out of a total of 1,300 in the district. Catholic clergymen, however, asserted that the number of converts (or ‘perverts’, as they styled them) was grossly exaggerated. There was a significant difference in the figure for ‘perverts’ given by the priests. They claimed that in the period 1849–52 there were 36 in the parish of Doon; 56 in Cappamore for the years 1848–53; and 77 in Pallasgreen for 1846–53. In addition to rejecting the Protestant numbers for converts, the Catholic clergy insisted that many of those who had ‘perverted’ were returning to the Roman Church. This happened at Doon as early as 1852, according to the local Catholic curate. It was believed that a mission organised in the parish had been successful in winning back many of them.

Certainly, by 1855 proselytism had ceased to be a problem for the Catholic Church at Doon, Pallasgreen and Cappamore. Daly’s addresses to the Irish Society in Waterford and at annual meetings in Dublin were noticeable for their lack of references to the three Limerick parishes after 1856. His hopes of a successful mission to convert Catholics were not realised.

Daly and national schools

In 1831 the chief secretary, Edward Stanley, announced the Whig government’s approval of a system of non-denominational elementary education, administered by a national board of education. This board gave assistance to local committees in building schools, published texts and contributed to teachers’ salaries. As it was Stanley’s intention that Catholic and Protestant children be educated together, the curriculum was secular in content, with provision for separate religious instruction. The Anglican Church reacted negatively to Stanley’s proposals. It believed that, as the state church, it should control a national education system. The distinction between religious and secular education, with its consequent limitation on the use of the Bible in the schoolroom, was deplored. Even before the National Board was set up, a meeting was held in the Rotunda on 10 January 1832, at which Robert Daly advocated the setting up of a Church education society. The first diocesan education society was formed in Tuam a year later, and other dioceses followed this example. In 1839 the diocesan societies formed a national organisation that styled itself the Church Education Society.

The cathedral’s reredos. (Sam Hutchison)

This society proceeded to dig an unbridgeable gulf between itself and the National Board of Education. It stated its ‘fixed determination never to avail of any system of education in which the scriptural instruction of every pupil is not recognised as the fundamental principle of Christian education’. The Authorised Version of the scriptures was to be used in the daily instruction of every child who attended the society’s schools. All the society’s members, inspectors and teachers had to be Anglicans. The children of other denominations were not obliged to learn the catechism and formularies of the church, but could be obliged to participate in scripture-reading.

As a bishop, Daly continued to be a vocal advocate of church education, and of the Church Education Society in particular. He was a regular main speaker at the society’s annual meetings. At the 1851 meeting he declared that he had been a conscientious supporter since its formation because it promoted the chief principle of Protestantism—the supremacy of God’s word. In 1853 he stated that since he believed that the scriptures contained all that was necessary for salvation, education had to be grounded on their inculcation. Daly used his position as a member of the House of Lords to promote the society’s objectives. On 11 April 1845 he presented sixteen petitions in parliament in support of scriptural education. In his own diocese he preached annually in Christ Church Cathedral in support of the society’s schools in Waterford.

While he was tireless in the cause of the Church Education Society, Daly was also unrelenting in his denunciations of the national system of education. Convinced that education had to be scripturally based, he rejected the social utility of the education provided in national schools. Speaking at the 1848 annual meeting of the Church Education Society, he contended that the social, moral and religious condition of the country had not been improved after sixteen years of national education. As proof of this assertion he referred to recent high-profile criminal cases: the convicted men had all attended national schools, according to Daly. On the basis of these facts, Daly declared that the character of the education in these schools had to be questioned and that ‘the education of the National Board was clearly a stimulant to crime’.

The diehard

At first the Church Education Society was a considerable success. In its first decade it was well supported by voluntary contributions. By mid-century, probably between £50,000 and £60,000 was being spent annually on primary schooling. Thus the society’s education system was well financed, and for a time proportionately more money was being spent on church schools than on the national schools.

During the 1850s, however, an increasing number of Anglicans favoured joining the national school system. The principal reason was financial. The maintenance of church schools represented a significant drain on resources. Parliament was petitioned in vain for a grant to the Church Education Society. Compounding the society’s difficulties was the fact that in 1855 the number of schools and children in the Anglican system declined in favour of the increasingly successful and popular national schools.

In 1860 Archbishop Beresford of Armagh addressed a circular to the patrons of schools in connection with the Clogher Diocesan Church Education Society. In it he pointed out that many of the society’s schools were in poor condition. He advised, reluctantly, that patrons could seek aid from the National Board of Education, if circumstances indicated the desirability of such a course of action. The primate was not abandoning the principles of the Church Education Society; he was advising that schools be placed under the national system, if it was deemed to be in the best interests of the pupils. The Church Education Society, however, split over the issue. A fanatical defence of the society was mounted by its enthusiasts.

Daly was one of the diehards. Throughout the 1860s he continued to address the society’s meetings, reiterating earlier themes. He linked the outbreak of civil war in the United States to the absence of scriptural education in that country. He repeated, in more trenchant terms, his belief that no Anglican could support any system of education that prevented the reading of scriptures. Those who did, he described as ‘sinful and criminal’. He asserted that the principles of the Church Education Society were so distinctly Protestant that it might be regarded as ‘one of the many lighthouses in the midst of darkness and superstition’. Daly made a virtue of the fact that his opinions on the issue of church schools and scriptural education remained unchanged. At the 1864 annual meeting of the Church Education Society he was reported as saying that ‘these 32 years had not altered his mind upon the subject; no, but he found the principle that they advocated at that time was more firmly fixed in his mind’.

Assessment

Robert Daly was not a complex man. His evangelical Protestantism inspired his religion and his responses to the various issues he encountered during a long life. For him the Bible was the repository of all truth. It was Daly’s belief in the central role of scripture in education that motivated one of the central features of his clerical and episcopal career—the rejection of the system of national education established in 1831 and the unstinting advocacy of the Church Education Society. It was this same conviction that inspired his attitude to Roman Catholicism and his proselytism.

The pulpit in Waterford Cathedral from which Daly would have preached.

It is true that many of the campaigns with which Daly was associated ultimately failed. This was the fate of proselytism. The national schools were not defeated; instead, the Church Education Society split. By the end of his life the Church of Ireland had been disestablished as an act of appeasement to the growing militancy, confidence and power of what he believed to be a heretical institution, the Roman Catholic Church. It would be wrong to describe his career as one of failure, however. Daly wanted Irish Anglicanism to be faithful to what he regarded as the Gospel imperative to bear witness to the truths of Protestantism. For him, controversy and proselytism affirmed the integrity of the Protestant faith. Being true to deeply held conscientious beliefs and giving them expression were ultimately more important than any successes or failures.

Eugene Broderick teaches in Our Lady of Mercy Secondary School, Waterford.

Further reading:

A. Acheson, A history of the Church of Ireland 1691–1996 (Dublin, 1997).

D. Bowen, The Protestant crusade in Ireland (Dublin, 1978).

H. Madden, Memoirs of the late Rt Rev. Robert Daly (London, 1875).