Beyond the Liffey and the Somme: Irish soldiers at the Tigris River, 1916

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2016), Volume 24, World War IMESOPOTAMIA WAS AMONGST THE HARSHEST THEATRES OF THE GREAT WAR

By Mark Phelan

While the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme understandably dominate the current commemorative landscape, the experiences of Irishmen under arms elsewhere in 1916 remain largely unknown. Far from the street fighting in Dublin and the killing fields of France, the Connaught Rangers spent the mid-point of the war fighting through the heart of Mesopotamia. Perceived as little more than a sideshow in the greater scheme of things, the fighting in the ‘cradle of civilisation’ rarely featured in contemporary reports, or indeed in subsequent historical literature. Even so, Mesopotamia was amongst the harshest theatres of the Great War, and the scene of a humiliating defeat for British Empire forces.

Background

Prior to the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war on the side of the Central Powers, a corps of British India Army troops occupied the head of the Persian Gulf. In so doing, this force secured the crucial oil fields that fed the Royal Navy, while maintaining British prestige in a remote part of the Arab world. The Indians, inspired by this inexpensive success, invaded modern-day Iraq in the summer of 1915, in the process capturing the city of Kut, which linked the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and from there advanced on Baghdad itself. Their luck ran out near the historic Arch of Ctesiphon, however. Here, almost 400 miles from the sea, overstretched columns led by Major-Gen. Charles Townshend fought a costly battle (21 November 1915) against the Turks. Shaken by this encounter, Townshend and his troops fell back on Kut, which superior enemy forces rapidly invested.

So it was that the Connaught Rangers formed part of an ad hoc relief force—the so-called ‘Tigris Corps’—that spent four months battering unsuccessfully against the Turkish defences before Kut. Known as ‘the Devil’s Own’, the Connaught Rangers regiment had a colourful history, fighting with distinction at Waterloo and thereafter policing the outer limits of the British Empire. In 1914 the second of the regiment’s two ‘line’ battalions had fought in France with the British Expeditionary Force, where it suffered severe casualties during the opening rounds of the Great War. Because of poor recruiting returns in the west of Ireland the lost men were not easily replaceable, and so the unit was disbanded in December 1914, with survivors being redeployed to 1st Battalion, Connaught Rangers.

British cavalry pose beside the Arch of Ctesiphon during the advance on Baghdad in March 1917. On 21 November 1915 it was the scene of a costly defeat by the Turks of Major-Gen. Charles Townshend’s India Army corps, who were subsequently besieged in Kut. Also known as Taq Kasra, the arch is the largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world, built in AD 540 by Sassanid-era Persians. (Private collection)

Action at Hanna

Arriving in Basra in January 1916, this force of approximately 1,000 men spent six days transhipping upriver to the front. This voyage brought the Irish soldiers alongside Qurna, otherwise known as the traditional location of the Garden of Eden. The ravages of time, however, ensured that the few men who knew their biblical geography felt underwhelmed by what was now simply a drab corner of the great alluvial plain. Disembarking at Orah (forward base camp of the Tigris Corps), the Connaughts were on hand to participate in a battle known as the ‘Action at Hanna’. Flanked by impassable marshes on one side and by the swollen River Tigris on the other, the Turkish defences at Hanna invited a direct assault. The British duly obliged on 21 January 1916; costing more than 2,700 casualties, including 273 Connaught Rangers, the attack failed completely. Moreover, inclement weather, allied to a chronic shortage of medical personnel and equipment, meant that the wounded suffered terribly. According to the battalion chaplain, Fr Peal,

‘It would be difficult to picture worse conditions … Everything was deficient. The stretchers were few, the bearers fagged out … the scene was heart-rending. Wounded and dying, European and native, all huddled together, soaked to the skin, coated with clay. The medical arrangements were nil. The medical officers, though most devoted, were too few to cope … No one who had not seen this could believe that such things were possible.’

The climate, which in winter included persistent rain, gale-force winds, violent hail and occasional snowstorms, had a major bearing on the British failure to break through to Kut, while a number of Connaught Rangers actually died of exposure. The constant rain and resulting floods not only placed further strain on an already difficult logistical situation but also compelled the relief force to attack over narrow fronts that might otherwise have been outflanked.

This pattern continued in March 1916, when the advance got under way once more. The renewed offensive floundered at the Dujaila redoubt. Although within sight of the minarets at Kut, this citadel likewise proved impervious to blunt British assaults. Kept in reserve, the Rangers took only an indirect part in this latest catastrophe. Conversely, the Connaughts played an important role in the subsequent general retirement to Orah. As final rearguard, the battalion fought a sharp encounter at a position known as ‘the Thorny Nullah’, which was perhaps the remotest outpost held by Irish troops on St Patrick’s Day 1916.

By then the battalion had absorbed 400 Territorial Army soldiers diverted from over-subscribed English regiments. Although fresh drafts from Ireland superseded these replacements in turn, for a large part of the Kut campaign the 1st Connaught Rangers thus incorporated as many British troops as Irish. Of course, not all Irish soldiers in the Tigris Corps soldiered in the Connaught Rangers; most notably, future IRA commander Tom Barry fought as a gunner with the Royal Field Artillery.

Meanwhile, the failure of the Dujaila operation meant that the Kut garrison tottered on the brink of collapse and capture. By early April, indeed, a handful of British aircraft kept the besieged men alive with irregular supply drops, while boiled grass had become a staple foodstuff within the city. In response, the Tigris Corps planned an eleventh-hour breakthrough. Concentrating three brigades on the right bank of the river, the British intended to rush enemy trenches opposite the village of Beit Aiessa. Anticipating this move, the Turks launched a surprise preliminary attack. Headed by the élite Second Constantinople Division, which had transferred to Mesopotamia in the wake of the Allied evacuation of Gallipoli, the Turkish offensive of 17 April 1916 drove at the centre of the British line. In consequence, the Connaught Rangers, their backs to the Tigris and under attack from three sides, had to fight a desperate night action in order to survive. This mêlée cost the battalion a further 187 casualties, before the Turks broke off the action and retired to their starting positions.

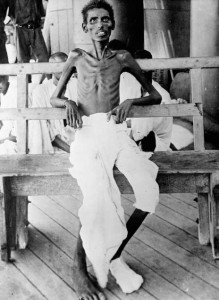

The besieged Kut garrison, two thirds of whom were Indian, surrendered on 29 April 1916. During the ensuing period of captivity in Anatolia many died from heat, disease and neglect. This emaciated sepoy was photographed after he had been liberated during an exchange of prisoners. (IWM)

Having held out for 147 days, Kut finally fell on 29 April 1916. Beforehand, the British made a futile attempt to bribe the Ottomans. Employing the celebrated Capt. T.E. Lawrence (‘of Arabia’) as a go-between, London offered the Turks £2,000,000 to let the garrison leave Kut and rejoin the British forces to the south. In the end, this ill-judged offer merely compounded the ignominy of the loss of Kut, which sent shockwaves throughout the Empire and across the Arab world. Meanwhile, more than 4,000 of the 12,000 men who surrendered were variously shot, starved or stoned to death during a death march into the Ottoman heartland, with several thousand more succumbing in POW camps located near the Syrian city of Aleppo.

Yet such atrocities were not the preserve of the Ottomans alone, and it is worth noting that the Connaughts played a dubious role in at least one unsavoury operation in the Mesopotamian theatre. Following a summer of intensive training, a heavily reinforced Tigris Corps recaptured Kut in the spring of 1917, and from there finally drove the Ottomans out of Baghdad. Confined during these operations to shepherding prisoners, cleaning up battlefield debris and unloading transports, the Rangers rarely crossed swords with Turkish regulars at this time. Nonetheless, the battalion did come under fire in the Feluja region, the interior of which was still controlled by hostile tribesmen and which was therefore highly dangerous for British columns or isolated soldiers who strayed too far from the safety of camp. The killing of one such wanderer prompted a typical punitive raid. As matter-of-factly recorded by the Connaught Rangers’ regimental history, on 5 May 1917 a scratch force of Irish and Gurkha troops punished

‘… Arab tribes for the murder of Colonel Magniac of the 27th Punjabis [Indian Army], who had been killed while walking near Feluja. Several villages of the tribes implicated were burned, the Arabs responsible for the crime being killed. Hostages for the good behaviour of the rest were taken, and a number of horses and cattle and other livestock were carried off as part of the penalty.’

For the remainder of 1917, the Connaughts conducted frequent sweeps of the Feluja hinterland and steeled themselves for an expected Turkish attempt to recapture Baghdad. The oppressive heat of the Mesopotamian summer prevented the British from launching anything other than half-hearted forays of their own at this time. Fully restored by fresh drafts of troops from Ireland, the battalion occasionally rotated into the surrounding hills, where fatigue parties prepared earthworks and other defences.

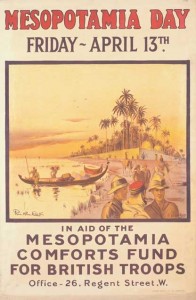

Poster calling on the public to support ‘Mesopotamia Day’, 13 April 1917. Élite society commonly organised this type of philanthropic event, which allowed the upper classes to demonstrate solidarity with the fighting men. Shortly beforehand, the Tigris Corps, of which the Connaught Rangers formed a part, had scored a notable success by capturing Baghdad. (IWM)

Incidentally, the 10th (Irish) Division, one of three ‘New Army’ divisions raised in Ireland in 1914, played a key role in the battle for the Holy Land before transferring to France in the spring of 1918. The 1st Connaught Rangers, meanwhile, was one of several units despatched from the Baghdad region to replace the departed Irish Division, and so saw further action during the triumphal British advance on Damascus and Aleppo, which precipitated the Ottoman collapse in October 1918.

Mark Phelan is a history Ph.D graduate of the National University of Ireland.

Read More:

Mutiny

Further reading

A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914–1918: Britain’s Mesopotamian Campaign (New York, 2009).

H.F.N. Jourdain, The Connaught Rangers, vol. 1 (London, 1924).

F.J. Moberly, Military operations: Mesopotamia (4 vols) (London, 1923–7).