Beyond Revisionism: reassessing the Great Irish Famine

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 4 (Winter 1995), The Famine, Volume 3

‘The day after the Ejectment’, Illustrated London News, 16 December 1848.

1995 marks the 150th anniversary of the first appearance of a new and deadly strain of potato blight in Ireland; a blight that reappeared in varying degrees over the next six years. As a consequence of the resultant food shortage and the more general disruption to economic life, by 1852 at least one million Irish people had died and a further one million had emigrated from Ireland. Thus, in the space of six years, Ireland lost twenty-five per cent of her population. The demographic decline continued and by 1901, the population of Ireland had fallen to four million. This population decline made Ireland unique within Europe as all other European countries experienced rapid population growth during the nineteenth century. Using the demographic criterion alone, the Famine was a human tragedy of immense proportions and one which was clearly a defining moment in the course of modern Irish history.

Self-censorship

So far, the anniversary of the appearance of the potato blight and subsequent Famine has attracted a lot of public and media attention in Ireland and, to a lesser extent, in Britain, America, Australia and Europe. The coincidence of the Northern Ireland peace process has increased international interest in Irish affairs, and a number of articles, TV and radio reports have seen the two events as being inextricably linked. A number of Irish academics have even stated that the current political climate has facilitated a new freedom in the discussion of past events. An underlying question is whether historians, social scientists, ethnographers, and even some government ministers and journalists, have allowed contemporary concerns to restrict historical debate. If this is the case, what are the implications of this self-censorship on interpretations and reinterpretations of the Irish Famine?

An attack on a potato store by starving people, Illustrated London News,18 June 1842.

Nationalist paradigm

To a large extent, the popular understanding of the Famine in Ireland still follows a traditional, nationalist paradigm. Within this model, ‘blame’ is generally attributed to key groupings, either within the British government or within the landlord class. To some extent, these beliefs were fostered by the state school system south of the border, which itself arose out of particular historical circumstances. In 1922, for example, the Free State government instructed history teachers that pupils should be ‘imbued with the ideals and aspirations of such men as Thomas Davis and Patrick Pearse’ and that they should emphasise ‘the continuity of the separatist idea from Tone to Pearse’ (see Francis T. Holohan, ‘History teaching in the Irish Free State 1922-35’ in HI Winter 1994). In Protestant schools in Northern Ireland, Irish history was rarely part of the curriculum (see Peter Collins, ‘History teaching in Northern Ireland’ in HI Spring 1995). Accordingly, in many Irish schools, a heroic but simplistic view of Irish history emerged, a morality story replete with heroes and villains. This approach, however, was subsequently challenged by the Irish academic establishment. In the 1930s, a number of leading Irish academics—following the lead of British historians earlier in the century—set an agenda for the study of Irish history, which placed it on a more professional and scientific basis in terms of research methods and source materials. At the same time this approach also demanded the systematic revision and challenging of received wisdoms or unquestioned assumptions. What was specific to Ireland, however, was the declared mission to challenge received nationalist myths, and by implication, although less centrally, loyalist myths. Thus, at the launch of the influential Irish Historical Studies journal in 1938, the editors stated their commitment to replace ‘interpretive distortions’ with ‘value-free history’. To a large extent, however, this debate took place within the rarefied atmosphere of academia and failed to percolate down into the schoolrooms either north or south of the border.

Interior of an Irish cabin.

Revisionism

In the 1960s, the study of history in many European countries was transformed as historians increasingly began to employ the methodologies of other disciplines and to develop new theoretical approaches. In Ireland, however, the dominant approach continued to be based on revising and destroying the traditional nationalist view of history. This approach became known as ‘revisionism’. As the IRA campaign intensified, revisionism gained a new prominence, in the battle for Irish hearts and minds, and challenging nationalist mythology became an important ideological preoccupation of a new generation of historians. A number of leading academics justified this construction on the grounds that IRA violence was linked directly with nationalist myths, although empirical evidence has been less forthcoming.

But did this new representation of Irish history really represent a new reality about Ireland’s past, particularly in relation to the Famine? The revisionist approach contained a number of inherent contradictions and limitations. From its origins, although revisionist history claimed to be value-free and objective, it had its own agenda or set of values, which varied over time and

Old Chapel Lane, Skibereen, County Cork.

in degrees of intensity. A key objective of Irish revisionism was to exorcise the ghost of nationalism from historical discourse and to replace it with historical narratives that persistently played down the separateness and the trauma, and derided the heroes and villains of Irish history. However, this declared determination of revisionism to destroy the ‘myths and untruths’ of populist historical consciousness has also limited the ability of revisionists to construct an alternative view of Irish history. Also, as Seamus Deane, the literary critic and poet has observed, in Ireland, there exists ‘the felt need for mythologies, heroic lineages and dreams of continuity’. Such myths and dreams need to be explained and deconstructed, not denied, destroyed or omitted, to suit a present convenience.

Symbiotic relationship with nationalism

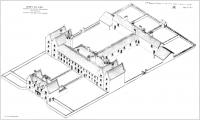

Plan of a workhouse designed to hold 400 to 800 people.

From the outset revisionism has depended for its existence on a symbiotic relationship with nationalism. Overall, this has limited the terms of reference of Irish history, and, as a consequence, Irish historiography– particularly Famine historiography– has been polarised within the confines of a concentric and narrow historical discourse. A false–but emotionally powerful–dichotomy has been created between traditional, reactionary nationalism and secular, modern revisionism. Irish historiography has, therefore, been constrained rather than extended as a result of revisionism.

How has Irish revisionism presented or represented historical narratives on the Famine? This has been achieved in a number of ways, but predominantly by rejecting popular perceptions, by deriding traditional accounts, and by destroying selectively the myths of the Famine years. A number of key issues relating to the Famine, however, have been particularly subjected to revisionist re-presentation.

Impact minimised and marginalised

Firstly, in revisionist interpretations the impact of the Famine on the development of modern Ireland has been minimised and marginalised. This is most apparent in the area of demography, particularly in revisionist accounts of excess mortality. In the influential but flawed book edited by Edwards and Williams and first published in 1956, both the editors and the contributors chose to avoid the unpalatable question of excess mortality, admitting only that ‘many, many people died’ (see James S. Donnelly, Jr., ‘The Great Famine: its interpreters, old and new’ in HI Autumn 1993). Other accounts have argued that the Famine merely accelerated demographic trends already under way before 1845.

How many people did die during the Famine? Although precise mortality figures are not available, estimates based on contemporary government returns and statistical analyses undertaken by econometric historians have computed excess mortality to have been at least one million people. This figure also coincides with accounts provided by contemporary government officials, including both the Irish constabulary and census commissioners. What is significant about this area of debate is the determination of revisionist historians to understate the impact, in particular the degree of mortality, resulting from the Famine. The death-toll resulting from the Irish Famine makes it unique in modern European and, indeed, world history. Other national famines since 1800 (e.g. Somalia in the 1990s or Ethiopia in the 1980s) have, in comparison, been far less demographically lethal than the Great Famine in Ireland.

Inevitable?

Secondly, there has been a tendency by revisionist historians to view the Famine and the consequent mortality as inevitable, the food shortage representing a long overdue Malthusian subsistence crisis. Furthermore, according to this interpretation, economic backwardness, over-population and administrative inefficiency, made Ireland unable to respond effectively to the sustained crisis of the Famine. But how backward was pre-Famine Ireland?

On the eve of the Famine, Ireland had one of the tallest, sturdiest, best fed and most fertile populations in Europe. The ubiquitous, and highly nutritious potato, was largely responsible for this. But Irish agriculture was not monolithic. By the 1840s, apart from growing sufficient potatoes to feed over five million people, and large numbers of farm animals and fowl, Ireland was also growing large quantities of grain, and by the 1840s was exporting sufficient grain to Britain to feed approximately two million people. Population density was highest in the north-east of Ireland which was also the most industrially advanced part of the country. Furthermore, Ireland at the time of the Famine had a highly developed administrative infra-structure including, since 1838, a national system of poor relief.

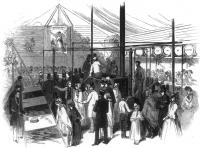

Alexis Soyers’ model soup kitchen in Dublin.

Issue of culpability avoided

Thirdly, the issue of culpability has been consistently avoided or denied in revisionist accounts. Moreover, both the landlords and the British government have been rehabilitated; the former frequently being shown as hapless victims themselves, and the latter, as being ignorant of the real state of affairs in Ireland, and lacking both the financial and administrative capability to alleviate the situation anyway.

The arguments regarding the role of the British government are not sustainable. In the summer of 1847, in the wake of the almost total second failure of the potato crop, the British government established soup kitchens throughout Ireland. At the peak of this scheme, over three million people, that is, forty per cent of the population, were receiving free rations of food

An Irish relief squadron distributing stores from HMS Valorous in the West of Ireland.

daily from the soup kitchens (which, even by the standard of contemporary famines, is a tremendous logistical achievement). To make this possible, a comprehensive and nation-wide machinery was created within Ireland in the space of only a few months. As a consequence of this scheme, mortality began to fall as, for the first and only time during the Famine, the problem of hunger was confronted directly. But the soup kitchens were only ever intended to be a short-term measure, and after the government closed them in the autumn of 1847, mortality again rose sharply. This brief episode, however, in which free food was provided on a nation-wide basis, demonstrated that the administrative capability to provide relief existed. Unfortunately for the poor of Ireland, the political and ideological will to continue the scheme did not exist (see Peter Gray, ‘The triumph of dogma: ideology and Famine relief’ in HI Summer 1995).

The financial commitment to alleviate Irish suffering was also inadequate. In the course of the Famine, (over a seven year period) the British government spent approximately £9.5 million on various relief schemes. The greatest portion (over £4.5 million) was expended on the ill-conceived public works schemes in the winter of 1846-7 which coincided with the period of highest Famine mortality, as a result of weak and hungry people being forced to undertake hard, physical labour as a ‘test’ of destitution. Furthermore, much of the money provided for relief was given as a loan to the Irish administration, which was both interest and principal bearing and had to be paid back immediately. Overall, the contribution of the British government over seven years, represented only about 0.2 per cent of the British GNP. Less than ten years later, in the course of the Crimean war (over a three year period), the British government spent £69 million on military expenditure.

Collective guilt?

Fourthly, and as an extension of the above, suffering, emotion and the sense of catastrophe, have been removed from revisionist interpretations of the Famine with clinical precision. The obscenity and degradation of starvation and Famine have been marginalised. Popular books on the Famine, notably those by Cecil Woodham-Smith and Robert Kee, which have placed suffering at the heart of the Famine, have been derided or dismissed by many within the academic establishment, although not, it has to be said, by the general reading public. The Great Hunger by Woodham Smith has sold almost sixty thousand hard back copies, making it the best-selling Irish history book of all time. Irish academics, with the honourable exception of Cormac Ó Gráda, have been less enthusiastic. Roy Foster, an influential revisionist, in an article optimistically entitled ‘We are all revisionists now’, pejoratively described Woodham Smith as ‘a zealous convert’, whilst, in 1964, a question in an undergraduate history examination paper in University College Dublin stated ‘The Great Hunger is a great novel. Discuss’.

A more invidious variation of this theme is that the population of Ireland today is descended from the survivors—sometimes even described as the ‘winners’—of the Famine period, thus implying a collective guilt amongst Irish people. Moreover, it has been suggested, that because a number of interest groups may have benefited from the economic dislocation of the Famine years, it is unfair to blame any other group for responding inadequately to the Famine. Survival and success, however, do not negate the suffering and starvation—either directly or indirectly—of the vast majority of the population.

No practical impediment to government intervention

Fifthly, there is a persistent claim that the British government in the 1840s possessed neither the practical nor the political means to either close the ports or import additional foodstuffs to Ireland. This is nonsense. Throughout the eighteenth century, and in 1817, 1822 and indeed, in 1845, the Irish and British governments imported food for resale in Ireland. In the subsistence crisis of 1782, an embargo was placed on the export of grain from Ireland, despite the opposition of Irish grain merchants. Furthermore, in the subsistence crisis of 1845 to 1847, which occurred throughout Europe, governments throughout the continent responded by temporarily closing their ports to exports (Portugal, Turkey, Russia, amongst others). This was, in fact, a traditional response to Famine conditions. Also, as the Corn Law crisis proved, there was no practical or ideological impediment to government intervention in the market place when it suited the purposes of the government.

Removed from centre stage

Sixthly, the Famine has been removed from the centre stage of nineteenth century Irish history. Instead, continuity is emphasised and it is argued that trends such as the decline of the Irish language, the change to pasture farming, and the demographic decline, would have occurred without the Famine, which was merely an accelerator in these processes. These views have resulted in curious assertions. For example, Raymond Crotty has argued that 1815 was far more important in the economic development of modern Ireland than the Famine years. Econometric historians such as O’Rourke, Ó Gráda and Mokyr have exposed the absurdity of this assertion by combining statistical interpretation with common sense.

Cecil Woodham- Smith’s The Great Hunger – the best selling Irish history book of all time.

Ideological minefield

Finally, revisionism has created an ideological minefield in Irish history, in which those historians who attempted to write traditional Irish history, based on a recognition that reality involves conflict as well as consensus, and cataclysm as well as continuity, were regarded as promoters of a backward nationalist ideology. In regard to the Famine, interpretations which hinted at the issue of culpability of the British government were pigeon-holed as being apologists and perpetrators of the nationalist struggle. Perhaps this accounts for the dearth of serious scholarly research on the Famine, most notably by historians within Ireland. Interestingly, the sesquicentenary commemoration has created a new interest and appears to be creating a new generation of what are becoming known in Ireland as ‘faminists’.

For many decades, the tragedy and significance of the Famine have been minimised, sanitised and marginalised by leading revisionist historians (and their supporters in the media). A declared purpose of Irish revisionism has been to ‘demythologise’ all Irish history, but in relation to the Famine, its target has been almost exclusively Irish nationalist history, and occasionally a mere caricature of it. Furthermore, revisionism has replaced nationalist historiography with a new orthodoxy based, at times, on equally facile myths and shibboleths. The process of challenging and revising should be an integral part of all historical writing. Irish revisionism, however, has stifled rather than stimulated historical debate on the Famine.

Although revisionism claims to be objective and value-free (a philosophical impossibility), in reality it has had a covert political agenda. As republican violence intensified, so did the determination of revisionists historians to destroy nationalist interpretations of Irish history. This has sometimes resulted in an equally unbalanced view emerging which, in the case of the Famine, has thrown the starving baby out with the purified bath-water.

Conclusion

Revisionism has polarised historical debate in Ireland and has stifled the more theoretical and philosophical approach to history which has developed elsewhere. Revisionism has dominated Irish historiography since the 1930s, and more intensely since the 1960s. However, as a new generation of historians emerges and more research is undertaken, it is unlikely that this domination will continue. This is not to say that revisionism in its various guises will disappear. As the American economist J.K. Galbraith has observed:

Faced with a choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everybody gets busy on the proof.

Christine Kinealy is a Fellow of the University of Liverpool.

Further reading:

C. Brady, Interpreting Irish History—the debate on historical revisionism (Dublin 1994).

C. Kinealy, This Great Calamity. The Irish Famine 1845-52 (Dublin 1994).

G. MacAtasney, Challenging an Orthodoxy. The Famine in Lurgan 1845-47 (Belfast forthcoming).

C. Ó Gráda, The Great Irish Famine (Dublin 1989).