‘Behind every great woman . . . ’:William Cecil and the Elizabethan conquest of Ireland

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2012), Volume 20

William Cecil, later Lord Burghley, served Queen Elizabeth I for 40 years (1558–98), first as principal secretary, later as lord high treasurer and throughout as an active member of her privy council. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Elizabeth and Ireland

But before we take this idea any further, it must be emphasised that the consensus among historians is that the queen was fiercely independent: she made decisions alone. A queen’s power, Elizabeth had no doubt, derived directly from God; she was, after all, Henry VIII’s daughter and so subject to no earthly authority. Cecil accepted that it was Elizabeth’s prerogative right to decide important things, for such was the birthright of princes, the very foundation of the world in which Cecil lived and lived to uphold. That he complained in private of how her hesitancy and vacillation at times placed her realms in real danger is a reflection of his powerlessness: that she, not he, called the shots. Yet historians have also shown that Elizabeth could be influenced and made to change her mind. This was evident, for example, in 1560, when Cecil threatened to resign because of Elizabeth’s reluctance to approve an English invasion of Scotland in support of the Protestant rebels. Against her deepest royal instincts, Elizabeth relented and, in this instance, followed the political and military course set out by Cecil. At other times, and in other circumstances, Elizabeth did not relent. Her twin refusals, to marry or to name a successor, placed her directly at odds with Cecil, but for Elizabeth these decisions were hers alone, so near as they were to her heart and to the mystery of her royal prerogative. More typically, however, Elizabeth accepted Cecil’s counsel and relied on him, and his legendary capacity for handling voluminous paperwork, to carry out the day-to-day business of administering her kingdoms.But did Cecil assume a more prominent role in Elizabeth’s decision-making where Ireland was concerned? The queen never visited Ireland. She also knew a great deal less about Ireland than England, the country of her birth, the place where she lived her entire life and which was the centre of her world. Ireland was a domestic concern in so far as it was not an independent territory like the kingdom of Scotland or France; but Ireland was not England and remained in many respects foreign to Elizabeth. Ireland had always occupied an ambiguous place in both the Tudor state and Tudor thinking. It was, like England, a kingdom, and part of a wider multiple monarchy, which Elizabeth ruled over and which was subject to the laws of England. In practice, however, parts of the kingdom, for much of Elizabeth’s reign, were beyond royal control, and government and society in those areas where the queen’s writ did run commonly deviated sharply from conditions in England. Even the legal and cultural position of Ireland’s inhabitants vis-à-vis the Crown was the subject of ambiguity. Neither Elizabeth nor the men who acted in her name could make up their minds whether the native population were her subjects at all, nor whether the state could accept Irishness as a legitimate form of cultural identity alongside Englishness. And then there was the problem arising from the Irishness and the adherence to Catholicism of Ireland’s English population, those men and women whose ancestors had settled in Ireland centuries earlier. Their identity was increasingly called into question as the century wore on. Elizabeth was said to have asked Christopher St Lawrence, Lord Howth, a leading member of the Old English community, whether he could speak English. Howth was greatly offended, but it was Elizabeth’s ignorance of her subjects in Ireland that was on show.

Laurence Nowell’s ‘A general description of England & Ireland’. Cecil is depicted in the lower right-hand corner, seated impatiently on an hourglass; Nowell, the cartographer, is slumped in the opposite corner, driven to drink. Cecil was said to have carried this map of the Tudor kingdoms with him wherever he went; the folds are visible still. (British Library)

A ‘careful father’ of Ireland

Bridging this divide between the Tudor kingdoms was William Cecil. Like his queen, he never set foot in Ireland, but unlike her he worked throughout his career to understand the kingdom and its inhabitants. Where Elizabeth showed herself in her interview with Howth to be badly uninformed about the sensitivities that were attached to language in Ireland, Cecil understood the subject so well that he could manipulate language itself. In a letter to Thomas Butler, earl of Ormond, Cecil invoked the ancient (and outlawed) Irish battle-cry, abú, in an effort to bolster the earl’s resolve in the face of a papally supported rebellion in Ireland: ‘so as now merely I must say Butler aboo, against all that cry as I hear in a new language Pope aboo’. Cecil struck just the right note with a man who was raised at court and was Elizabeth’s cousin but who was also the head of one of the oldest English noble houses in Ireland. How, we might ask, did Cecil acquire such an intimate knowledge of Ireland? He penned, received and studied thousands of papers on subjects relating to Ireland and the Crown’s political, economic, social and religious policies there. He personally compiled genealogies of Ireland’s Irish and English families, so as to better understand the identities of the men who made up the lineages that continued to dominate parts of the kingdom. He peered into corners of the realm which had yet to be touched by royal government (along with those that had) through the many maps which were drawn at his behest and which often bear his notes locating key people and places. When he deemed the information flowing to him from and about Ireland insufficient, he was not above seeking out further information among the records in the Tower of London and in Irish histories and genealogies that he asked to be sent to him. Cecil came to know Ireland in greater depth and detail than anyone at Elizabeth’s court, and the queen relied heavily on Cecil’s expertise when Ireland was discussed. William Cecil’s consistent attention to Ireland was not lost on members of the Tudor political establishment: he became towards the end of his career in the eyes of some the ‘careful father’ of the kingdom of Ireland, with Elizabeth implicitly cast as its distant and disinterested mother.

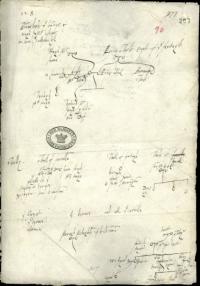

One of dozens of genealogies (in this case of the O’Byrnes and O’Tooles of Wicklow) of Ireland’s Irish and English families personally compiled by Cecil. (UK National Archives, Kew)

The problem of Ireland in the Tudor state

It is tempting from our modern vantage point to see William Cecil as a proto-prime minister being accorded, or seeking to grasp, additional power and influence in the early modern state; but he was at all times reluctant to assume primary responsibility for Ireland. For most of his career he worked on Ireland in conjunction with his fellow councillors, going so far at one point as to see established a formal subcommittee with responsibility for Ireland. Yet for Cecil first-hand experience always trumped any indirect knowledge that might be acquired in England. It was those men ‘on the ground’ in the queen’s service, most especially the viceroy, who, he insisted, should dictate the course of Tudor rule in Ireland. The reality of the situation, however, was that these men looked to England for direction: it was Elizabeth who appointed them, Elizabeth who might recall them and Elizabeth upon whom they relied for financial and military support. The result was often paralysis of political action, with the court looking to Ireland for direction and vice versa. To break the impasse, Cecil argued that Elizabeth should allow her viceroy to act without reference to England and furnish him with the necessary provisions to see Ireland made, as he put it, ‘a kingdom in deed as hath often been referred to in name’. The queen was unprepared to consent to either. In 1567 Elizabeth agreed to send William Cecil to Ireland to function as her special representative there. But Cecil did not go. It speaks volumes about the Anglo-Irish relationship that Cecil was unprepared to risk all so as to achieve the same sort of decisive shift in the basic structure of the Anglo-Irish relationship as he did in the Anglo-Scottish relationship in 1560. The threat posed by disaffected elements in Ireland, and more importantly by foreign powers prepared to support them, was not especially imminent in 1567, but this was not the case later in the century when rebellion raged in Ireland and England was at war with Spain. During these heady years Cecil explained to Francis Walsingham that Elizabeth must give her governors in Ireland

‘. . . absolute authority to do all things by their discretions to pacify the storms, and if Her Majesty were in a ship upon the seas, and tempest should arise she must give authority to the master and pilots to govern the ship and much more, where neither she nor her councillors in England are present, the pilot of the ship of Ireland is not to be restrained but let to his own discretion’.

Conclusion

Though William Cecil laboured for decades to make Ireland into a fully functioning Tudor kingdom modelled on England, there was no ‘Cecilian conquest’ of Ireland. Elizabeth’s belief in her prerogative right to make important decisions, her ignorance of Ireland notwithstanding, combined with Cecil’s unwillingness to step beyond his role as the queen’s servant to insist more forcefully that his sovereign radically alter the structures of the Anglo-Irish relationship ensured that there could not be. But is it any more appropriate to speak of an ‘Elizabethan conquest of Ireland’? It is, of course, true that royal authority was, during Elizabeth’s reign, extended to all parts of the island, and that in her last years a grand showing of English military might vanquished the queen’s enemies there, but as a concept the ‘Elizabethan conquest’ can be misleading. Unlike her imperious father, who later in his reign pursued a deliberate policy of integrating Ireland into the Tudor state, Elizabeth was wedded to no consistent strategy for her Irish kingdom; ‘conquest’, moreover, implies a sharp, coherent effort on the part of the regime to effect integration and elides the halting, incoherent and incomplete process that unfolded in Ireland. So, if there was no power behind the throne, and if she who occupied the seat of power provided little active leadership when it came to Ireland, how is the greatest failure of one of early modern Europe’s most successful regimes to be explained? Apart from looking to the many fine scholarly attempts that seek to address this important question in terms of such faceless and complex phenomena as state formation or colonisation, we may in conclusion advance the more human suggestion that the absence of anyone in effect piloting the ship, to borrow Cecil’s analogy, contributed to the unfortunate means whereby Ireland became part of what was shortly to become a ‘British’ state. HI Christopher Maginn is Associate Professor of History at Fordham University, New York.

Further reading:

S. Alford, Burghley: William Cecil at the court of Elizabeth I (New Haven, 2008).C. Brady, The chief governors: the rise and fall of reform government in Tudor Ireland, 1534–88 (Cambridge, 1994).C. Maginn, William Cecil, Ireland, and the Tudor state (Oxford, 2012).