Bastardy—the stain of illegitimacy in medieval Ireland

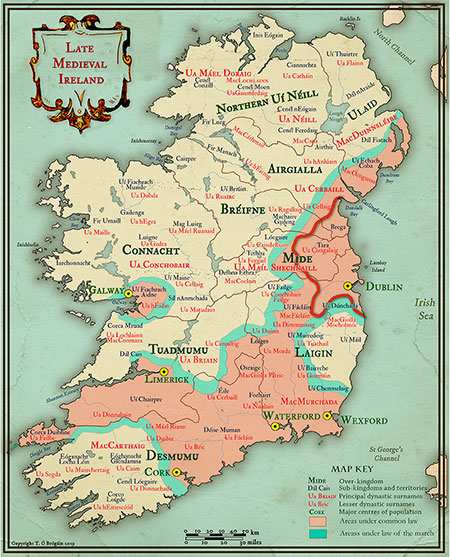

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2020), Volume 28Four different legal systems operated, with profound consequences for the concept of legitimacy.

By Cormac T. Hickey

In force until the Flight of the Earls and the collapse of the Gaelic order in the early seventeenth century, brehon law did not distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate children in terms of either rights or responsibilities, but brehon law was not the only legal order functioning on the island. Within the English-controlled areas, such as the Pale and some isolated towns and cities, it was the nascent English common law—only just asserting itself as a truly national system of law and justice across the Irish Sea at this time—that was enforced. A few short decades after the initial conquest, English control over Ireland began gradually to recede, with many areas that had been under the crook of the Plantagenet administration reverting entirely to Gaelic control.

The English areas were run under common law and Irish areas under brehon law. Things were not quite so simple, however. In the border regions, known as the marches, between Gaelic and English-controlled areas there grew up a hodgepodge of both systems (and some local customs) which was described as the ‘law of the march’ in the royal statutes seeking to rid Ireland of this hybrid creation. There is, however, no surviving documentation of the system and so we do not know what rules it applied to inheritance cases. Finally, canon law was applied in relation to wills and marriages. Thus four different systems operated in late medieval Ireland and this had profound consequences in the specific context of the legal concept of legitimacy. For those born outside wedlock, quality of life, opportunities and ultimate wealth depended to a large extent on where they were born.

Brehon law and illegitimacy

The English monarchy constantly pilloried brehon law, characterising it as so ungodly that it needed to be eradicated for the good of the Irish people. A common complaint related to its relatively lax attitude to marriage. Cáin Lánamna, an early tract on the topic, lists the nine different types of union permitted under this system, in addition to a set of conditions for both divorce and separation. What truly catches our eye, though, is to be found elsewhere. Maccslechta, an ancient law tract, lists the three categories of sons who were permitted to inherit—including, crucially, both the sons of betrothed concubines and acknowledged sons. In essence, all that mattered under brehon law was that paternity was clear.

Above: Ireland’s most famous medieval marriage—detail from the watercolour version of Daniel Maclise’s The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife. (NGI)

The same text illustrates the numerous categories of sons who were barred from inheriting their father’s property, including the macc muine (son conceived in the bushes), the macc raite (an abandoned child taken into the house) and the macc tointen (son of two potential fathers). Here the lack of certainty surrounding paternity creates the barrier to inheritance. Other cases, such as the macc focraí (proclaimed or outlawed son) and the macc ingor (son who neglects to care for his father), are excluded from inheritance on account of the sons’ actions. The sons of underage girls (since the girl’s family would not have consented to the union) and prostitutes were also barred from inheriting.

Canon law versus common law

This lax attitude to marital status in the determination of legitimacy contrasted with the positions adopted by the other systems. No records of the law of the march remain, but both canon and common law adopted different approaches than brehon law.

Intriguingly—and contrary to what we might expect—canon law was more relaxed about the topic than common law, probably because land was of prime importance in the common law system and any method of restricting ownership, and thereby copper-fastening a family’s wealth, was happily grasped by the Anglo-Norman administrators. In contrast, brehon law considered family superior to land. Under canon law, a child born outside wedlock was subsequently legitimised if the parents later married. The leniency of canon law’s approach is illustrated by the number of medieval bishops whose illegitimacy was little hindrance to their advancement within the Church. John de Sandford, archbishop of Dublin in the late thirteenth century, was illegitimate but could hold high office, although he needed papal dispensation to hold benefices above the value of £500.

The issue first appeared in common law in the Anstey case in the 1160s, when the parents’ illegal marriage prevented their child from inheriting. In 1236 clause nine of the Statutes of Merton noted the attempt of bishops to have the law changed to reflect the canon law position that a subsequent marriage legitimised such children. The barons, however, refused to countenance any such change, and the common law remained steadfast in its stance that only children born within marriage could inherit land. The following year, Henry III issued a terse reminder—this time in Ireland—that people seeking inheritance from this position were not to be sent to the ecclesiastical courts, ‘because the clergy hold a person born before marriage as legitimate’.

Before the decade was out the issue would arise again. The same monarch, just a year after the previous instruction, intervened in the case of Richard de Hyde. He ordered that the English custom was to be followed in Ireland and that land held by a bastard was to revert to the lord of whom he had held the land on his death. Later, after the death of Robert Ruffus, there was some debate as to whether he was legitimate or a bastard, with the latter being presumed and his estate accordingly reverting to the king.

Unlikely rapprochements and predictable divergences

At first glance, the positions of canon and brehon law on this topic are poles apart. On further inspection, however, certain parallels appear between the two systems, despite their clear differences.

Both systems required not so much the formal rites of a marriage ceremony as the guarantee of a stable couple. In allowing the subsequent legitimisation of children born before marriage, canon law did not require the ceremony of marriage to precede birth in order for children to be legitimate, as the later marriage guaranteed the stability of the couple in accordance with Church rites. Similarly, in allowing the legitimisation of children born to a betrothed concubine, brehon law privileged the stability of the union over any need for formal marriage. Clearly, however, the systems diverged on the need to marry at some point: marriage was irrelevant to legitimacy in brehon law but necessary in its canon law equivalent.

Above: Effigy of King Henry III of England in Westminster Abbey. In 1237 he issued a terse reminder—this time in Ireland—that people seeking inheritance were not to be sent to the ecclesiastical courts, ‘because the clergy hold a person born before marriage as legitimate’.

In effect, what both systems sought was certainty that the children were indeed of the couple. In canon law this certainty was achieved through the couple’s subsequent marriage, while in brehon law the fact that marriage was not necessary meant that other criteria were used to exclude children whose paternity was in question from the inheritance.

The greatest divergence between the systems (even between canon and common law, which appear to be closely tied) was the motivation that lay behind their respective approaches to legitimacy. The common law’s stringent approach allowed for properties to be retained in large blocks, which facilitated stability. For instance, the partition of the Marshall inheritance in Ireland following the death of Anselm Marshall in 1245 is considered one of the causes of the subsequent collapse in Anglo-Norman control of the island, though it was the absentee nature of the lords (rather than their number) that was the key issue.

For canon law, the promotion of Church teaching on marriage was the primary motivation in allowing the subsequent legitimisation of bastard children. Brehon law followed the familial influence, which had an impact on so many areas of law in medieval Ireland. The proof of belonging to the family—as evidenced by certainty of paternity and the permission of both families given to the union—was deemed sufficient to inherit, regardless of adherence to various marriage rules.

While the systems occasionally converged in some aspects of their approaches to legitimacy, their ultimate motivations and thus their end results were quite varied.

Conclusion

The patchwork quilt of legal systems in the wake of the twelfth-century conquest of Ireland left unmistakable marks on many aspects of society. Where you lived dictated the legal response to any problem, and in a society so strongly driven by the possession of land few areas had as much impact as the issue of legitimacy.

While common law recognised only children born after their parents’ marriage, canon law allowed for the subsequent legitimisation of children and brehon law allowed inheritance by children born to concubines or acknowledged women as well as those born to a legally married wife. In spite of the clear differences between the approaches of the different systems, certain similarities nevertheless appear. At the heart of the issue was the certainty of paternity—both canon and brehon law allowed for the legitimisation of children through different avenues. Neither system needed the marriage to precede birth, as the common law did.

Ultimately, these different systems had varying motivations—whether the restriction of land ownership, the strengthening of adherence to Church teaching or the central place of family in Gaelic society—in their consideration of legitimacy. These divergences were a symptom of the complex legal reality of late medieval Ireland and meant that eligibility to inherit varied according to location.

Cormac T. Hickey is a Master’s by research law student at the University of Edinburgh, studying medieval Irish legal history.

FURTHER READING

A. Cosgrove, ‘Marriage in medieval Ireland’, History Ireland 2 (3) (1994).

C. Donahue, ‘The canon law on the formation of marriage and social practice in the later Middle Ages’, Journal of Family History 8 (2) (1983).

F. Kelly, A guide to early Irish law (Dublin, 1988).

S. McDougall, ‘The strange history of the “bastard” in medieval Europe’, The Wire,18 June 2017.